GST, as an indirect tax, is collected by a person from another person for onward payment to the Government. Though it is a destination-based consumption tax on businesses, the charge and legal liability to pay tax has to be vested onto a specific person (the subject). In case such subject is missing, the taxing statute would lose its purpose as the implementation of the same would become impossible. The word ‘person’ encompasses within its fold not only natural persons like individuals but also artificial persons like firms, AOPs, trusts, companies, etc.

The term ‘person’ has been defined u/s 2(84) of the Central Goods & Services Tax Act, 2017 as under:

(84) ‘person’ includes —

(a) an individual;

(b) a Hindu Undivided Family;

(c) a company;

(d) a firm;

(e) a Limited Liability Partnership;

(f) an association of persons or a body of individuals, whether incorporated or not, in India or outside India;

(g) any corporation established by or under any Central Act, State Act or Provincial Act or a Government company as defined in clause (45) of section 2 of the Companies Act, 2013 (18 of 2013);

(h) any body corporate incorporated by or under the laws of a country outside India;

(i) a co-operative society registered under any law relating to co-operative societies;

(j) a local authority;

(k) Central Government or a State Government;

(l) society as defined under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 (21 of 1860);

(m) trust; and

(n) every artificial juridical person, not falling within any of the above.

As can be seen from the above, the term ‘person’ has been very widely defined to cover, apart from individuals, different types of entities / associations / societies, etc., as well as Government at different levels, i.e., Central, State as well as local authorities. However, mere inclusion in the definition of person would not result in liability of GST unless such person gets covered within the charging provision u/s 9 of the CGST Act, 2017.

CHARGING SECTION & LIABILITY TO PAY TAX

Section 9(1) imposes a levy of GST on all intra-state supplies of goods or services, or both. Having so imposed the tax, the said provision also defines that the tax shall be paid by ‘the’ taxable person. The definition of the term taxable person u/s 2(107) read with the provisions of section 22 would suggest that the taxable person shall generally be the supplier. The exceptions to this general rule are provided in subsequent provisions as under:

• Section 9(3) provides that in notified cases, the tax on supply shall be paid on reverse charge basis by the recipient;

• Section 9(4) provides that in notified cases, the tax on supply received from unregistered persons shall be paid by the registered person on reverse charge basis; and

• Section 9(5) provides that in case of notified services, the tax shall be paid by the Electronic Commerce Operator (ECO) through which the said services are supplied, by treating such ECO as the supplier.

Thus, the important terms emanating from the charging section are taxable person, registered person, supplier and recipient, and in order to enforce levy of tax on a person, a person needs to be classified under any of the said baskets. If a person is not a taxable person, or a registered person or a supplier or a recipient, the liability to pay tax cannot be fastened on him. In other words, the person needs to be specified as ‘a person liable to pay tax’ in one of the persons mentioned above for

the liability to be fastened on him. The above position was laid down by the Supreme Court in the context of service tax while dealing with Rule 2(d)(xii) and (xvii) of the Service Tax Rules, 1994 which cast responsibility on the service receiver to pay service tax. The levy was struck down in the case of Laghu Udyog Bharati vs. UoI [1999 (112) ELT 356 (SC)] as well as in UoI vs. Indian National Shipowners Association [2010 (017) STR 0J57 (SC)].

In the context of GST also, this aspect has been dealt with by the Gujarat High Court in the case of Mohit Minerals Private Limited vs. UoI [2020 (33) GSTL 321 (Guj)]. The issue before the Court was the validity of Entry 10 of Notification 10/2017-IT (Rate) which casts liability on the importer to pay tax on the freight component of goods imported on CIF basis. The liability to pay tax was cast on a notional value, being 10% of the CIF value of the goods imported. One of the contentions raised before the Court challenging the validity of the rate entry was that the privity of contract was between a foreign shipping line as a supplier and the foreign exporter of goods as a recipient and the Indian importer was not a privy to the transaction. As such, the importer could not be treated as a recipient of service and, therefore, the liability to pay tax u/s 9(3) was not triggered. This was accepted by the Gujarat High Court which held as under:

148. In our opinion, the writ-applicant cannot be made liable to pay tax on some supposed theory that the importer is directly or indirectly recipient of the service. The term ‘recipient’ has to be read in the sense in which it has been defined under the Act. There is no room for any interference or logic in the tax laws.

149. If the definition of the term ‘recipient’ is overlooked or ignored, then the writ-applicant would become the recipient of all the goods which goes into the manufacture / production of goods and all the services which have been availed by the foreign exporter for such purposes. Such reasoning which leads to a harsh and arbitrary result has to be avoided, particularly when the term has been expressly defined by the Legislature. Thus, the writ-applicant cannot be said to be the recipient of the supply of the ocean freight service and no tax can be collected from the writ-applicant.

The principle emanating from the above decision is that a person has to be either a supplier or a recipient in order to be held liable to pay tax. In view of the specific deeming fiction in the law itself treating an E-Commerce Operator as a deemed supplier in some cases, even such ECO may be held liable for payment of tax.

PERSON: CONCEPT OF DISTINCTNESS

GST is a transaction tax driven by contract, whether oral or written. This necessitates that all the elements essential for a valid contract need to be present before the levy can be triggered. Keeping this aspect in mind and to achieve the concept of consumption-based tax, i.e., tax revenue should flow to the State where the consumption takes place, section 25 provides that a person who has obtained / is required to obtain registration in one or more State / Union Territory shall, in respect of each such registration, be treated as a distinct person. Further, Schedule I, Entry 2 deems supply of goods or services between such distinct persons as supply, even if made without consideration.

At this juncture, it is relevant to refer to the service tax provisions wherein establishment of a person in a taxable territory and any of his other establishments in a non-taxable territory were treated as distinct establishments of the same person. The implication of this provision was that the Indian HO and its foreign branch were treated as separate entities, though their accounts were ultimately consolidated and for all legal purposes they were treated as one entity.

The above provision had resulted in certain litigation. In 3I Infotech Limited vs. Commissioner [2017 (51) STR 305 (Tri-Mum)], the issue before the Tribunal was liability to pay tax on expenditure incurred by the foreign branches of an Indian company but disclosed in the financial statements which were prepared on a consolidated basis. In this case, a show cause notice proposed recovery of service tax under reverse charge on expenses of such foreign branches. The Tribunal, however, set aside the demand and held as under:

12. We note that Rule 3(iii) of Taxation of Services (Provided from Outside India and Received in India), Rules, 2006 includes ‘business auxiliary services’ but is restricted to such as are received by a recipient located in India for use in relation to business or commerce. The thrust of the Rules is to identify the manner of receipt of service in India in the three categories, viz., in relation to the object of the service, the place of performance and the location of the recipient. We are concerned with the residuary aspect of location of recipient. The Adjudicating Commissioner has not rendered a finding that the appellant is the recipient of service, indeed, he could have done so only by examining the relationship between the appellant and branch in the context of the payments effected to the foreign service provider which he, probably, did not feel obliged to do in the absence of any allegation to that effect in the show cause notice. Unless the recipient is located in India, section 66A cannot be invoked.

Similarly, in the context of airlines, the Tribunal was seized with the question of determining whether or not service tax was payable under reverse charge on payment made to foreign service providers for the centralised reservation system. The challenge was primarily because the payments were made by the Head Office of the airlines. Therefore, in case of international airlines, the entire payment was made by the airlines from their base country, including for bookings done from India from where the said airlines operated. A show cause notice was issued to the foreign airlines to recover service tax under reverse charge mechanism to the extent payments were made pertaining to India bookings. The matter was ultimately decided by the Larger Bench of the Tribunal in the case of British Airways vs. Commissioner [2014 (36) STR 598 (Tri-Del)] wherein the Court set aside the demand and held as under:

46. In view of the foregoing discussions, M/s British Airways, India, has to be treated as a separate person. If that be so, in view of the admitted position that the contract between CRS / GDS companies is not with M/s British Airways, India and is only (sic) that M/s British Airways, UK, the present appellant cannot be held to be the recipient of the services so as to make him liable to pay service tax, on reverse charge basis, in terms of the provisions of section 66A. The said issue stands discussed by the Learned Member (Technical) in his impugned order, by giving an example with which I am in full agreement.

The above decisions indicate that while determining who is the recipient of service the one who is entering into the contract becomes more relevant, even if it is the same legal entity. The challenges would be more especially when this deeming fiction becomes applicable in the context of domestic branches. Let us try to understand the challenges with the help of a few examples:

1. A company incurs marketing expenses for its products which are sold through its regional branches. For accounting and MIS purposes, the company distributes the expenses to the regional branches and the expenses (along with the corresponding ITC) appears in the trial balance of each such branch, though there is only one corresponding invoice. The issue that would arise is who is the recipient of service, who is eligible to claim the input tax credit, and what will be the implications of the Schedule I Entry 2.

2. Similarly, issues may arise in the context of cases where the liability to pay tax is under reverse charge. For instance, a company having a centralised transport department books freight from its Head Office in State A for movement of goods from State B to State C. The company is registered in all the three States. The issue that would remain is whether the RCM liability is to be paid in State A from where the expense has been incurred or State B / C where the services are consumed?

3. The branch office situated in Gujarat has incurred certain expenses towards marketing and promotion. However, the vendor has raised the invoice to the Head Office and disclosed it accordingly in its GST returns, while the expense has been booked by the Gujarat office as it had raised the PO. Who can claim the input tax credit in such cases?

4. Even in case of revenue, while the main revenue would be tagged to the respective locations from where the supply has been made, there can be instances for other income where such identification is not available, or the identification is done erroneously. Let’s take the example of canteen charges which are collected by the company from the employees’ salary on a monthly basis. It is possible that the charges for all employees may be accounted for in one State only. Will there be any implications if the company pays the tax on such recoveries in the State where the recovery is accounted, or the company would be mandatorily required to make payment in the State to which the revenue pertains?

Each of the above situations needs changes at the organisational level, with a need to incorporate branch level accounting, sensitising the personnel with the importance of synchronisation of the invoicing location vis-à-vis the PO location vis-à-vis the accounting location (be it for income / expenditure). A lapse on any one aspect would have substantial impact on the organisation, including financial costs, as claiming of credit in wrong location would not only result in denial of input tax credit at the wrong location and recovery along with interest / penalty, but the correct location may lose out on such credits if not identified within the appropriate timelines. Similarly, even in case of revenue, if the tax is paid from the wrong location, it is likely that the tax authorities might still demand tax from the branch which was actually liable to pay the tax as a supplier of service, resulting in duplicate tax as well as bearing the same, along with interest / penalties as applicable.

Further, the deeming fiction is also inserted to associations where mutuality applies w.r.e.f. 1st July, 2017 wherein activities or transactions between such associations and their members are deemed to be supply. This is to negate the applicability of the decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Calcutta Club Ltd. [2019 (29) GSTL 545 (SC)] wherein it was held that in the case of mutual associations, no VAT / Service Tax was leviable. However, the amendment has not been notified till date and in most likelihood will also be subjected to judicial scrutiny from the GST perspective.

INTERPLAY BETWEEN TAXABLE PERSON AND REGISTERED PERSON

The term ‘taxable person’ has been defined u/s 2(107) as under:

(107) ‘taxable person’ means a person who is registered or liable to be registered u/s 22 or u/s 24;

On a plain reading, it is apparent that any person who is liable to be registered or has voluntarily obtained registration is treated as a taxable person. A person is liable to be registered u/s 22 in the following cases:

• Turnover crossing the prescribed limit,

• Liability of successor in case of succession by way of transfer of business, or

• Liability of transferee on transfer of business / part thereof by way of merger, de-merger, etc.

Similarly, section 24 lays down the situation in which a person shall be liable to obtain registration notwithstanding the turnover limit prescribed u/s 22. However, section 22/24 merely determines the point when a person becomes liable to registration and treats such person as a taxable person. Once the registration is obtained by such person, either in view of section 22/24 or voluntarily, such person becomes a registered person. A ‘registered person’ has been defined u/s 2(94) to mean a person registered u/s 25 but does not include a person holding a Unique Identity Number.

The fundamental difference between a taxable person and a registered person forthcoming from the above is that the concept of taxable person is meant to determine a person who is liable to comply with the GST provisions, including obtaining registration, collecting and paying taxes. Such a person, when he complies with the provisions by obtaining registration, becomes a registered person and the procedural aspects of the GST law, such as input tax credit, filing of returns, assessments, etc., become applicable to such registered persons. For instance, the levy provision u/s 9(1) provides that the tax shall be paid by the taxable person. There can be instances where a person liable to obtain registration has failed to do so. Such a person cannot shirk away from his liability to pay tax on supplies made merely because he is not registered, as long as such person continues to be a taxable person, i.e., there is a liability on him to obtain registration. Similarly, liability to pay is cast on a taxable person in the following cases:

• In case of interest u/s 50, for cases where there is a failure to pay, the liability to pay interest is cast on ‘person’, i.e., both, a person already registered, as well as a person liable to registration but not registered.

However, the term ‘registered person’ is referred primarily in provisions relating to claiming of any benefit / procedural aspects. For example, the provisions relating to claim of input tax credit (section 16), exercising option to pay tax under composition scheme (section 10) or filing of returns / refund claims, etc., (Chapter IX) refer to a registered person. This is because the said provisions deal with the procedural aspects which a person cannot comply with unless such person has obtained registration and becomes a registered person.

Therefore, if it is ultimately held that a person was required to obtain registration but failed to do so, he is likely to lose out on claim of input tax credit as section 16(1), the enabling section, entitles only a registered person to take input tax credit. In view of the decision in the case of Spenta International Limited vs. Commissioner [2007 (216) ELT 133 (Tri-LB)], it is a settled position of law that eligibility of credit has to be decided at the time of receipt of inputs.

Therefore, it is apparent that unless a person obtains registration he shall not be entitled to take input tax credit on inward supplies received prior to grant of registration. However, the exception granted u/s 18(1)(a) in case of registration u/s 22/24 and voluntary registration u/s 25(3) will be available, though the same is restricted only to the extent of inputs held in stock. This is a departure from the position under the CENVAT regime where the Karnataka High Court has, in the case of mPortal India Wireless Solutions Private Limited [2012 (27) STR 134 (Kar)] held that registration is not a prerequisite for claim of CENVAT Credit.

LIABILITY TO PAY TAX UNDER ‘REVERSE CHARGE’

While section 9(1), which is the general section, imposes a liability to pay tax on the taxable person supplying the goods, sections 9(3) and 9(4) provide for cases where the liability to pay tax has been shifted to the recipient of the goods or services, or both. However, there is a difference in both the provisions.

Section 9(3) notifies the category of goods or services or both where the tax is payable by the recipient of such goods or services, or both. However, section 9(4) notifies the class of registered persons who shall on receipt of notified supply of goods or services or both, be liable to pay tax under reverse charge. The primary distinction in case of reverse charge u/s 9(3) and 9(4) is that section 9(3) applies to a recipient receiving the notified goods or services or both, as defined u/s 2(93), while section 9(4) applies to notified class of registered person receiving the notified goods or services or both. Therefore, for applicability of reverse charge u/s 9(3), a person needs to be classified as ‘recipient’,” while in the case of the latter, the person needs to be both, recipient as well as registered person.

It therefore becomes essential to analyse who is the recipient in the context of GST. The same is defined u/s 2(93) as under:

(93) ‘recipient’ of supply of goods or services or both, means —

(a) where a consideration is payable for the supply of goods or services or both, the person who is liable to pay that consideration;

(b) where no consideration is payable for the supply of goods, the person to whom the goods are delivered or made available, or to whom possession or use of the goods is given or made available; and

(c) where no consideration is payable for the supply of a service, the person to whom the service is rendered,

and any reference to a person to whom a supply is made shall be construed as a reference to the recipient of the supply and shall include an agent acting as such on behalf of the recipient in relation to the goods or services or both supplied;

It is evident that the definition merely refers to ‘the person’. The person may or may not be a taxable person / registered person. In such a situation, the liability to pay tax in case of supplies notified u/s 9(3) shall be on the recipient. This, coupled with the provisions of section 24(iii) which provides for compulsory registration in case of persons liable to pay tax under reverse charge, would trigger the need for registration even if such person is otherwise not liable to registration.

Therefore, in cases where the supply is notified u/s 9(3), the recipient (if not a registered person) would need to analyse whether or not an exemption has been granted for such supply. For instance, in case of reverse charge on security services / rent-a-cab services, there is no exemption provided under the exemption notification. Therefore, even if there is a single instance of such payments, the liability to obtain registration and pay the tax would get triggered.

This would apply even in cases where there is an exemption from obtaining registration. For instance, a supplier exclusively engaged in making exempt supplies is not required to obtain registration u/s 22(1) even if his aggregate turnover exceeds Rs. 20 lakhs as the same applies only to taxable supplies. However, if such a person receives security services / rent-a-cab services which are notified u/s 9(3), such person would be required to obtain registration in view of section 24(iii) and pay the tax (with no corresponding credits) and comply with the prescribed provisions.

It is also important to note that in quite a few cases exemption has also been granted. For instance, a charitable trust carrying out charitable activities and not liable to pay GST u/s 9(1) would not be liable to obtain registration u/s 22. However, if the same trust purchases software from outside India, the same will be taxable as import of service (which does not require to be in the course or furtherance of business) and in such cases the liability to obtain GST registration and comply with the provisions gets triggered. However, in view of Entry 10 of Notification 9/2017-IT (Rate), such services and certain other cases are exempted from the levy of tax and, therefore, the need to obtain registration does not get triggered in such cases.

However, when it comes to section 9(4), the liability to pay tax triggers only when the person is a registered person, i.e., he has obtained registration u/s 25 and is covered within the class of registered persons notified therein. Currently, the notified class of registered persons liable to pay tax u/s 9(4) on supplies received from unregistered suppliers is a promoter as defined u/s 2(zk) of the Real Estate (Regulation & Development) Act, 2016.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF TAXABLE PERSONS

Under the GST law, a person also has an option to obtain registration as a Casual Taxable Person (‘CTP’) / Non-resident taxable person (’NRTP’). The terms ‘casual taxable person’ and ‘non-resident taxable person’ have been defined u/s 2 as under:

(20) ‘casual taxable person’ means a person who occasionally undertakes transactions involving supply of goods or services or both in the course or furtherance of business, whether as principal, agent or in any other capacity, in a State or a Union Territory where he has no fixed place of business.

(77) ‘non-resident taxable person’ means any person who occasionally undertakes transactions involving supply of goods or services or both whether as principal or agent or in any other capacity, but who has no fixed place of business or residence in India;

As can be seen from the above, registration as NRTP / CTP is applicable in case of a supplier intending to make a taxable supply of goods or services or both from a State / Union Territory where such supplier, being a taxable person, has no permanent fixed place of business in the said State / Union Territory. The only distinction between NRTP and CTP is that while the concept of NRTP applies to a person who has no fixed place of business / residence in India, the concept of CTP applies to a person who has a fixed place of business / residence in India, but not in the State / UT from where such person occasionally makes the taxable supply.

In a recent decision, the Supreme Court in Commercial Tax Officer, Bharatpur vs. Bhagat Singh [2021 (46) GSTL 3 (SC)] held that a person can be treated as casual taxable person even if he carries out a single transaction. There is no need for multiple transactions in order to obtain registration as a Casual Taxable Person.

The need to opt for CTP / NRTP would generally apply in cases where goods are sent for exhibition in a different State and sold at the exhibition itself. Similarly, even Event Management Companies can opt for this concept to optimise credits (especially on inward supplies falling under the property basket). However, in case of handicraft goods, an exemption has been granted from obtaining registration.

It is, however, important to note that CTP / NRTP is compulsorily required to obtain registration u/s 24(ii) and 24(v), respectively. Therefore, a person who has a fixed place of business in Maharashtra and is not liable to be registered u/s 22(1) or 24 and intends to make a taxable supply in Gujarat where he has no fixed place of business, will be required to obtain registration even if his turnover from Gujarat or aggregate turnover is not likely to cross the threshold limit prescribed u/s 22(1). Secondly, the need to register as CTP / NRTP will be triggered only in a case where taxable supply of goods or services or both is intended to be made. This was recently held by the AAR in the case of Ascen Hyveg Pvt. Ltd. [2021 (48) GSTL 386 (AAR–GST–Har)].

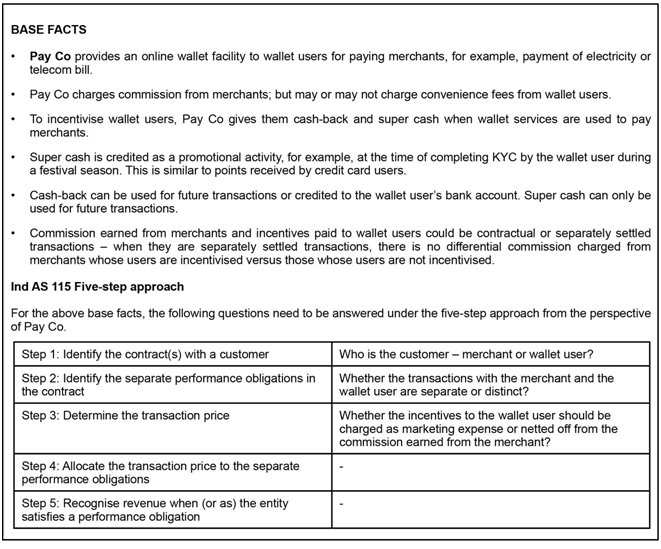

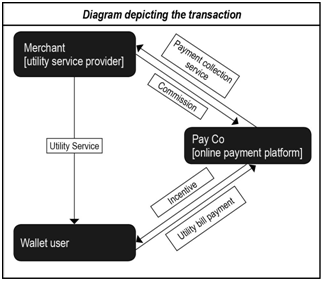

E-COMMERCE OPERATOR

In these modern times, online service providers through their online portals have started providing the service of connecting the supplier and the recipient for a charge. The transaction is between the supplier and the recipient but is facilitated by the online portals (such as OLA, Uber, Zomato, etc.). The online portals charge a fee from the supplier or recipient or both. At times, what happens is that both supplier as well as recipient are not registered and, therefore, the transaction escapes the tax net.

Keeping this aspect in mind, the liability to pay tax on such transactions was cast on such online portals, i.e., E-Commerce Operators, through which the services are being supplied. The relevant definitions are:

(45) ‘electronic commerce operator’ means any person who owns, operates or manages digital or electronic facility or platform for electronic commerce;

(44) ‘electronic commerce’ means the supply of goods or services or both, including digital products over digital or electronic network;

Currently, the notified class of services where the liability to pay tax is cast on the ECO are:

• Service by way of transportation of passengers by radio-taxi, motor-cab, maxi-cab and motorcycle;

• Service by way of providing hotel accommodations except where the person actually supplying the service is liable for registration u/s 22(1), i.e., his turnover exceeds the threshold limit;

• Services by way of housekeeping, such as plumbing, carpentering, etc., except where the person actually supplying the service is liable for registration u/s 22(1), i.e., his turnover exceeds the threshold limit;

• Restaurant services supplied through ECO (Swiggy, Zomato, etc.) are also likely to be covered u/s 9(5) w.e.f. 1st January, 2022.

It is imperative to note that in the above cases the liability to pay tax is shifted to the ECO. This is not a case of reverse charge. Therefore, from suppliers’ perspective, especially unregistered suppliers, no tax can be demanded from such suppliers where the ECO has already paid the tax. Further, such unregistered suppliers, supplying exclusively through E-commerce operators are also exempted from obtaining registration if their turnover exceeds Rs. 20 lakhs.

The ECO is also required to collect tax at source @ 1% on the net value of taxable supplies (other than notified supplies) made through it by the registered suppliers.

PERSON – PRINCIPAL – AGENT RELATIONSHIPS UNDER GST

The transactions of principal / agency are governed by the provisions of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 and the terms of the arrangement between such parties. Under GST, the supply of goods by a principal to his agent or by an agent to his principal is deemed to be a supply for the purpose of section 7, even if made without a consideration. However, the same does not extend to services. Therefore, any movement of goods by a principal to his agent or otherwise, be it intra-state or interstate, has to be under the cover of a tax invoice.

It is also important to note that the liability of the principal and his agent in respect of goods supplied / received by the agent shall be joint and several, and in case the agent fails to make payment of the due tax, the same can be recovered from the principal.

However, the deeming fiction has not been extended to services. This can lead to certain issues. Let’s take the example of an agent paying the GTA for transport services. The agent is also a registered person and the GTA recognises the agent as the recipient of service. In such cases, the question arises as to who shall pay GST under reverse charge? And if the agent has discharged the liability under reverse charge, can the same be demanded again from the principal?

Even under the pre-GST regime, there have been disputes on taxability in case of P2A transactions. The primary dispute has been determining whether the relationship of principal – agency exists between the two parties or not, be it travel agents, advertising agencies, freight forwarders, etc. For instance, in case of discounts / incentives given by vehicle manufacturers to the dealers where the Department had alleged Business Auxiliary Services, the Tribunal had stuck down the demand, concluding that such discounts were nothing but a reduction in purchase price (Refer Commissioner vs. Sai Service Station Ltd. [2014 (35) STR 625 (Tri-Mum)].

Even in case of freight forwarders, where the freight forwarders traded in cargo space and the Department had demanded service tax on the trading profits, the demand was set aside in the case of Greenwich Meridian Logistics (I) Pvt. Ltd. [2016 (43) STR 215 (Tri-Mum)]. Similarly, in case of advertising agencies, the Tribunal had in the case of Euro RSCG Advertising Ltd. [2007 (7) STR 277 (Tri-Bang)] held that the agency was liable to pay tax only on the amounts collected from the advertiser / client and not the publisher. It is, however, important to note that the basis for this dispute was that the freight charges / print advertising charges were exempt from service tax, which is not so in the context of GST. It is therefore unlikely that the disputes will continue under GST.

As can be seen from the above, even though the tax was discharged on the transaction complying with the principles of destination-based taxation (as the POS was correctly disclosed), the authorities still issued demand notice without appreciating the fact that the tax liability was exhausted. This demonstrates that while dealing with service transactions taxpayers will have to be very careful in taking positions, as any position is likely to be scrutinised by tax authorities and any instances involving non-payment of tax are likely to be looked at adversely.

Of course, on the issue of discharge of liability / person liable to pay tax, in the context of Service Tax, the Tribunal has, in the case of Reliance Securities Ltd. vs. Commissioner [2019 (20) GSTL 265 (Tri-Mum)], held that if the agent has paid the service tax liability, the principal would not be liable to pay tax on the same again on his share. It remains to be seen whether the said principle will be followed in the context of GST also.

PERSONS – WAREHOUSE / GODOWN OWNER / OPERATOR AND TRANSPORTERS

Apart from the above, there are various instances where a person, though not being a taxable person (i.e., registered or not liable to be registered), is required to comply with various requirements under the law. For instance, a warehouse / godown owner / operator and transporter who is not registered is required to maintain records of the consignor, consignee and other relevant details of the goods in the manner prescribed u/r 58. Such person is required to obtain a unique enrolment number by making an application in Form GST ENR-01 / ENR-02, respectively.

In addition, the following details are required to be maintained by such persons:

• In case of warehouse / godown owner / operator, period for which particulars of goods remain in the warehouse along with particulars relating to receipt, dispatch, movement and disposal of such goods;

• In case of transporter, record of goods transported, delivered and stored in transit along with the GSTIN of the consignor and the consignee.

The Proper Officer has the powers to carry out inspection, search and seizure at the premises of the above suppliers, i.e., transporter or warehouse / godown owner / operator u/s 67. Such officer also has powers to issue directions to the custodian of the goods to not remove, part with or deal with such goods without prior approval.

Similarly, when the goods are in movement, it is the responsibility of the transporter to ensure that the prescribed documents are in possession for verification during the movement. If the vehicle is intercepted during movement and the prescribed documents are not available with the transporter in support of the goods being transported, they are liable to confiscation.

PROCEEDINGS A PERSON MAY BE SUBJECTED TO

On the basis of the classification of a person, either as a taxable person, a registered person or otherwise, a distinction exists in the provisions relating to assessment, audit, recovery and penalties. While the concept of self-assessment u/s 59 refers to the registered person requiring such person to self-assess his liability, the option of provisional assessment u/s 60 is made available to a taxable person. Therefore, if a person has doubts over whether he is liable to be registered, he has an option to opt for provisional assessment.

Similarly, separate provisions have been prescribed u/s 63 for a taxable person who fails to obtain registration or has obtained registration but the same has been cancelled u/s 29(2). The reason for the assessment u/s 63 not being applicable to a taxable person registered under GST is that the taxable person who is registered is to be subjected to scrutiny u/s 61, assessment u/s 62 in case of non-filing of returns, audit by tax authorities u/s 65, and special audit u/s 66.

However, in case of recovery proceedings u/s 73 or u/s 74, the provisions refer to ‘the person’, implying that the provisions shall apply to both, a taxable person (thus including a registered person) and a person who is not liable to be registered and opts to be an unregistered person. The appeal provisions have also been similarly drafted.

However, depending on the nature of the contravention, the person on whom penalty can be imposed is based on the nature of contravention. For instance, penalty for specific offences listed u/s 122 is applicable only on a taxable person, while penalty for failure to furnish information return u/s 150 or statistics is leviable on any person. Similarly, the general penalty prescribed u/s 125, which deals with levy of penalty for any offence not covered above, is leviable on any person, irrespective of whether such a person is a registered person or not.

CONCLUSION

The GST law recognises different classes of persons and classification of a person would make such person liable to either pay tax, claim credit or be subject to various proceedings, or even require such person to comply with other provisions of the law. Therefore, it is always important that it is determined which particular provisions are applicable to a person, and whenever any proceedings are being commenced on such a person, it is ensured that such person can be subjected to the said proceedings else the very basis of the proceedings can be challenged before the courts.