Transmission of securities occurs by operation of law upon a shareholder’s death, distinct from voluntary inter vivos transfers,. While nominees provide immediate administrative continuity, they act only as trustees; beneficial ownership remains governed by succession laws or Wills,. For transmission, companies require death certificates and legal evidence like probates or succession certificates, especially during disputes,. SEBI’s new “TLH” code (effective 2026) streamlines tax reporting for transfers from nominees to heirs,. To bypass complex probate processes, many individuals utilize private family trusts, removing assets from their personal estate during their lifetime.

INTRODUCTION

Securities have become the most valuable asset for many individuals. This is all the more true for promoters of listed companies. In such a scenario, when a shareholder dies, the transmission of the securities held by him in an effective and efficient manner becomes very vital. While the law in this respect is a mix of Legislation and Decisions, the practical aspects have issues at times. Let us examine the position with respect to the transmission of securities when a shareholder dies.

TESTATE OR INTESTATE SUCCESSION?

Depending upon whether the individual shareholder who dies left behind a valid Will, or not, the transmission would be testamentary (under a Will) or intestate (under the relevant succession law). In case of intestate succession, the law applicable would be the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 or the Indian Succession Act, 1925 of Portuguese Civil Code or the Uniform Civil Code (only where applicable) or the Shariah Law, depending upon the faith professed by the deceased.

LAW ON TRANSMISSION OF SHARES

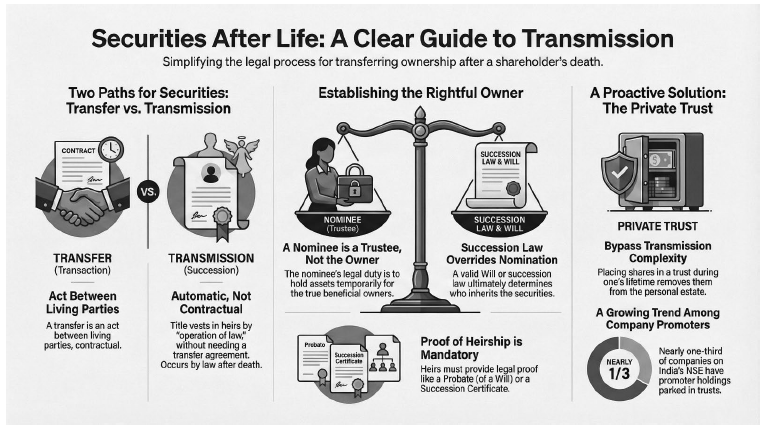

A decision of the Gauhati High Court in Hemendra Prasad Barooah vs. Bahadur Tea Co. (P.) Ltd. [1991] 70 Comp Case 792 (Gauhati) has explained the meaning of transmission of shares. The word ‘transfer’ was an act of the parties or of the law, by which title to property was conveyed from one person to another. Inter vivos transfer was a transfer from one living person to another. It was a transfer of property during the lifetime of the owner and it was to be distinguished from succession where the property passed on death. Under section 211 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, the executor of a deceased person was the legal representative for all purposes, and all the property of the deceased person vested in him as such. The word ‘transmission’ had been used in the Companies Act in contradistinction to the word ‘transfer’. ‘Transmission’ was referable to devolution of title by operation of law. It may be by succession or by testamentary transfer. As regards ‘transfer’, it had been used to mean inter vivos transfer. The executor of a deceased person was his legal representative for all purposes, and all the property of the deceased vested in him as such. Therefore, the right to the shares or other interest of the deceased member in the company devolved on the executor of the deceased by operation of law as distinguished from inter vivos transfer. But the executors did not become members of the company unless their names were registered. In such a situation, on death, the right of deceased to the shares or other interest as a member in the company devolved on executors as they are the legal representatives of the deceased. The right to the shares or other interest in the company, of the deceased member, passed or transmitted to the executors.

S.44 of the Companies Act, 2013 states that the shares or debentures or other interest of any member in a company shall be movable property transferable in the manner provided by the Articles of the company. The NCLAT Chennai Bench has explained the procedure for transmission of shares in its decision in the case of Emaar Hills Township Pvt. Ltd. vs. Telangana State Industrial Infrastructure Corporation, (2022) ibclaw.in 992 NCLAT.

In respect of `Transfer of Securities’, there are two parties to the `Contract’, i.e., Transferor and Transferee. Such a transfer is like any other `commercial transaction’. However, in the case of `Transmission of Shares’, there is no `Transferor’ or `Transferee’, as `Shares’ vests in favour of a `Person’, by an `Operation of Law’, like that of an `inheritance’ of `property’. Where `Transmission of Shares’ takes place, by an `operation of law’, there is no further requirement, to be carried out, like executing an `instrument of Transfer’ and `Company Law Register’; the `Securities’ on receipt of intimation of `Transmission’, in favour of a `Person’, to whom the `Shares’ are `transmitted’. Moreover, when `Title’ to the `Shares’, came to `Vest’ in another `Person’, by an `Operation of Law’, it was not essential to submit a Transfer Form.

A decision of the NCLAT, Chennai Bench in Avanti Metals Pvt. Ltd. vs. Alkesh Gupta, [2024] 158 taxmann.com 650 (NCLAT – Chennai) has succinctly summarised the law with respect to transmission of securities. The NLCAT analysed s.44 of the Companies Act and held that when s.44 of the Act provided that shares of any member in a Company were required to be transferred in the mode and manner provided for under the Articles of Association of the Company, the prescribed requirements were bound to be followed. In this case, the Articles required the production of a valid succession certificate. The NCLAT held that production of a succession certificate was a necessary requirement for transmission and since there was a dispute as to heirship of the deceased shareholder, the Company was within its right to refuse transfer of shares, until such succession dispute was resolved by a Competent Court of Law. It held that a Company cannot refuse `Transmission of Shares’, once the `legal heirs’ proved his/her entitlement to them, through a `Probate’, a `Succession Certificate’. It was pointed out that `transfer’ was an act of parties or law by which the title to the party was conveyed from one person to another. This would lapse by `Operation of Law’ or `Succession’. `Transmission of Shares’ on the basis of `Will’ could raise complicated issues which required an `evidence’, to be read by the parties and need to be determined by a Court of Law. It further held that a Will probated by a `Competent Court’ was binding on the parties, unless it is set aside by a `Competent Forum’. If the `Probate Proceedings’ were pending in a `Civil Court’, then the `Petition’ under the `Companies Act’ for `rectification of register’ would not be maintainable. Where there was a dispute as to the heirship of a `deceased shareholder’, the Company could refuse `transfer of shares’, until such dispute was resolved by a `Competent Court of Law’.

It relied upon the decision in the case of Thenappa Chettiar vs. Indian Overseas Bank Ltd. [1943] 13 Comp Case 202 (Madras) which held that a succession certificate can be granted, not merely in respect of a debt but also in respect of a security, which was defined in the Indian Succession Act to include a share in a company. The application for a certificate had to set out the right which the petitioner claimed and also the debts and securities in respect of which it was applied for. The grant of the certificate, specifying the debts and the securities, empowered the person to whom it was granted, not merely to receive the interest or the dividends on the securities, but also to negotiate or transfer them. The grant of a certificate gives to the grantee a good title to recover the debt or the security and affords full indemnity to all persons dealing with him. The High Court also held that transfer and transmission were quite distinct from each other. The former was based upon an act of parties; the latter was the result of the operation of law. In the case of a transmission of shares, they continued to be subject to the original liabilities, and if there was any lien on the shares for any sums due, the lien would subsist, notwithstanding the devolution of the shares.

The Supreme Court in Aruna Oswal vs. Pankaj Oswal [2020] 221 Comp Case 374 (SC) has held that a dispute as to inheritance of shares was eminently a civil dispute which could not be decided in proceedings of oppression and mismanagement.

ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION

The Articles of Association of a Company generally provides for the procedure that a company will adopt in respect of an application made for transmission of shares. The Companies Act, 2013 Table F provides for the model form of the Articles. Regulation 23 states that on the death of a member, the survivor or survivors where the member was a joint holder, and his nominee or nominees or legal representatives where he was a sole holder, shall be the only persons recognised by the company as having any title to his interest in the shares.

It further states that any person becoming entitled to shares in consequence of the death of a member may, upon such evidence being produced as may from time to time properly be required by the Board of Directors and subject as hereinafter provided, elect, either

(a) to be registered himself as holder of the share; or

(b) to make such transfer of the share as the deceased member could have made

Moreover, the Board of Directors shall have the same right to decline or suspend registration as it would have had, if the deceased member had transferred the share before his death.

JOINT OR SINGLE HOLDING?

Since most shares and securities are held in a dematerialised form, the transmission needs to be seen with the Demat Account. The hierarchy in a demat account is that on demise of a joint holder the 2nd holder would become the account holder and on the demise of both the holders, the nominee, if any, would become the account holder.

In case of a single holder in a demat account, the nominee, if any, would become the account holder.

However, it should be remembered that the joint holder and the nominee would only be the legal owner and not the beneficial owner of the account. In this respect the decision of the Supreme Court in Shakti Yezdani vs. Jayanand Jayant Salgaonkar, 2024 (4) SCC 642 has settled the issue once and for all. The issue of whether a nomination overrides a Will in respect of securities and demat accounts had been a contentious issue for long. The Supreme Court analysed various Supreme Court decisions in case of bank accounts, insurance policies, PPF, etc., which had held that a Will overrides a nomination. It then analysed the provisions of the Companies Act and the Depositories Act, 1996 and held that the same legal principle even applies in the case of securities and a demat account. The vesting of the shares/securities in the nominee under the Companies Act, 1956 and the Depositories Act, 1996 was only for a limited purpose, i.e., to enable the Company to deal with the securities thereof, in the immediate aftermath of the shareholder’s death and to avoid uncertainty as to the holder of the securities, which could hamper the smooth functioning of the affairs of the company. The Court rejected the argument that the intention of the shareholder was to bequeath the shares/securities absolutely to the nominee, to the exclusion of any other persons (including legal representatives) and hence, constituted a ‘statutory testament. The Court held that this was because the Companies Act did not deal with succession, nor did it override the laws of succession. It was beyond the scope of the company’s affairs to facilitate the succession planning of the shareholder. In case of a Will, it was upon the administrator or executor under the Indian Succession Act, 1925, or in case of intestate succession, the laws of succession to determine the line of succession. Ultimately, it concluded that the nomination process did not override the succession laws. Simply said, there was no third mode of succession that the scheme of the Companies Act, 1956 (pari materia provisions in Companies Act, 2013) and the Depositories Act, 1996 aimed or intended to provide!

SEBI LODR PROVISIONS

The SEBI (LODR) Regulations, 2015 also provide for the procedure of transmission of shares in the case of a listed company. R.40 provides that the listed entity shall comply with all procedural requirements as specified in Schedule VII to the Regulations with respect to transmission of securities. Further, transmission of securities held in physical or dematerialised form shall be effected only in dematerialised form. The key requirements specified in the Regulations are as follows:

(1) In case of transmission of securities, where the securities are held in single name with nomination, the following documents shall be submitted:

(a) duly signed transmission request form by the nominee;

(b) death certificate;

(c) PAN of the nominee

(2) In case of transmission of securities, where the securities are held in single name without nomination, the following documents shall be submitted:

(a) a notarized affidavit from all legal heir(s) to the effect of identification and claim of legal ownership to the securities. In case the legal heir(s) are named in a Succession Certificate or Probate of Will or Will or Letter of Administration an affidavit from these legal heir(s)/claimant(s) alone shall be sufficient;

(b) duly signed transmission request form by the legal heir(s)/claimant(s);

(c) death certificate

(d) PAN of the legal heir(s)/claimant(s)

(e) a copy of Succession Certificate or Probate of Will or Will or Letter of Administration or Court Decree; Where a copy of Legal Heirship Certificate is submitted, a No Objection Certificate from all non-claimants must also be given

(f) for cases where the value of securities is up to ₹5 lakhs per listed entity in case of securities held in physical mode, and up to ₹15 lakhs per beneficial owner in case of securities held in dematerialized mode, as on date of application, and where the documents mentioned in para (e) are not available, the legal heir(s) /claimant(s) may submit the following documents:

(i) no objection certificate from all legal heir(s) stating that they do not object to such transmission or copy of family settlement deed executed by all the legal heirs; and

(ii) a notarized indemnity bond indemnifying the Share Transfer Agent/ listed entity,

The listed entity may, at its discretion, enhance the value of securities from the threshold limit of ₹5 lakhs, in case of securities held in physical mode.

SEBI’S NEW TLH CODE

In September 2025, SEBI introduced a new reporting code ‘TLH’ to simplify transmission of securities from nominees to legal heirs. It recognises that the nominee acts as a Trustee of the securities of the original security holder and transfers the securities to the legal heir as per succession plan.

As per earlier procedure for effecting such transfers, the nominee, while transferring the securities to legal heir had to effectuate an off-market transfer. This unfortunately in some cases led to the nominee being assessed for capital gains tax as on a transfer. SEBI recognised that while clause (iii) of Section 47 of the Income-tax Act, 1961, exempted such transmission from being considered as a “transfer”, this process caused inconvenience to the nominee.

In order to alleviate this inconvenience, a Working Group (“WG”) was formed. The WG, based on engagement with the CBDT, recommended that to address the issue, reporting entities should use the reason code “TLH” (i.e. Transmission to Legal Heirs), while reporting such transactions to the CBDT.

Accordingly, as a part of ease of doing investment and in order to streamline the process of transmission of securities from nominee to legal heir and resolve the above-mentioned issues related to taxation, SEBI has now specified that a standard reason code viz. “TLH” shall be used by the reporting entities while reporting the transmission of securities from nominee to legal heir, to the CBDT so as to enable proper application of the provisions of the Income Tax Act, 1961. This should be used in Demat Slips executed by the nominee who is transferring shares to the legal heir. SEBI has directed RTAs, Listed Issuers, Depositories and Depository Participants to make necessary system changes and implement this proposal with effect from 1st January 2026.

TRUSTS AS AN ALTERNATIVE SOLUTION

The entire judicial debate explained above over nominee vs beneficial owner, transmission, succession certificates/probates is relevant only in the case of securities held by the deceased in his individual name. Thus, these issues come to the fore when the shares where held by an individual and he/she passes away. However, in case the same are settled on a private family trust then all these problems cease to exist. A transfer to a trust is made during one’s lifetime and the shares then cease to be a part of the settlor’s estate. Accordingly, transmission and succession to these shares is not relevant even after the settlor passes away since they would constitute assets of the trust and not of the estate. In countries levying Estate Duty/Inheritance Tax, gifting assets to a trust could sometimes also help reduce this tax incidence. However, the trusts need to be structured properly after paying due heed to income tax/gift tax and other relevant issues. This has led to promoters of several listed companies parking their promoter holdings in private irrevocable trusts. Some press reports indicate that nearly one-third of all companies listed on the NSE have promoter holding parked in trusts and this number is rapidly increasing.

CONCLUSION

Promoter shares and for that matter shares, in general, form a large component of the estate of many families. If due care and caution is not paid to their succession/inheritance, then these could get locked up in legal tangles and controversies.