A. NOTIFICATIONS

i) Notification No.10/2024-Central Tax dated 29th May, 2024 & Notification No.11/2024-Central Tax dated 30th May, 2024

The above notifications seek to amend the Notification no. 02/2017-CT dated 19th June, 2017, which is regarding Territorial Jurisdiction of Principal Commissioner / Commissioner of Central Tax, etc. There are substitutions for changes in jurisdiction.

ii) Notification No.12/2024-Central Tax dated 10th July, 2024

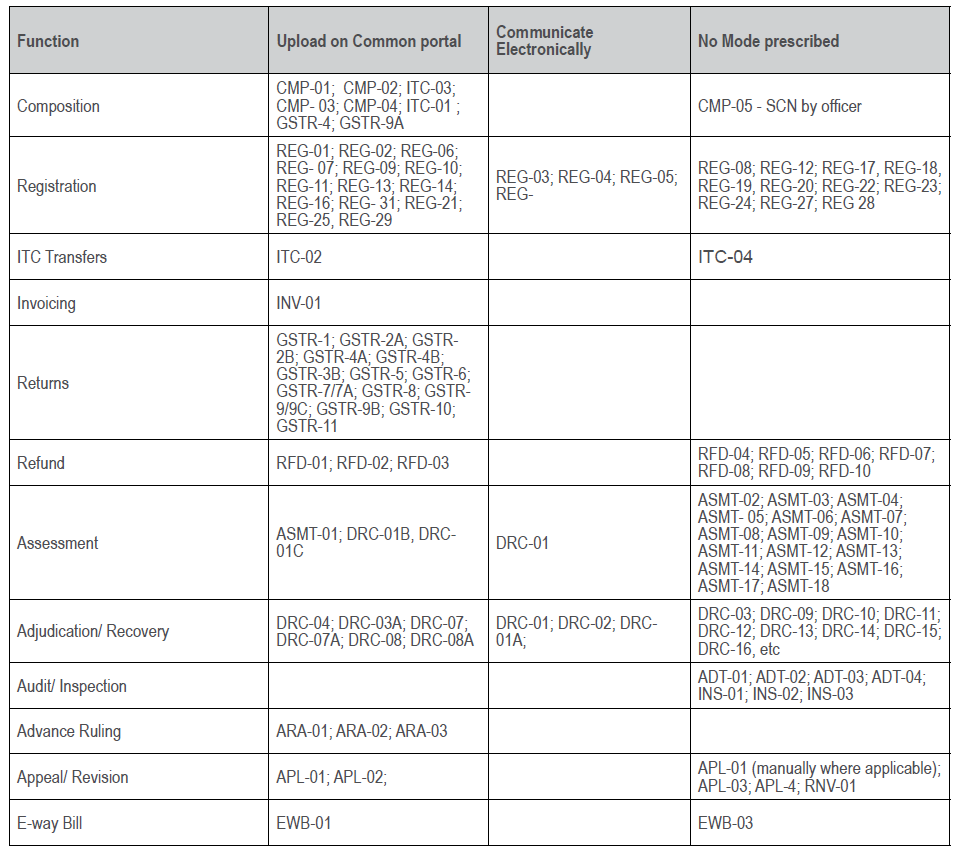

The above notification seeks to make amendments in CGST Rules, 2017. Amongst other, there are amendments in Rules relating to returns, ISD, refund and appeal to Tribunal, etc.

iii) Notification No.13/2024-Central Tax dated 10th July, 2024

The above notification seeks to rescind Notification no. 27/2022-Central Tax dated 26th December, 2022, which was regarding applicability of Rule 8(4A) of CGST Rules.

iv) Notification No.14/2024-Central Tax dated 10th July, 2024

The above notification seeks to exempt the registered person, whose aggregate turnover in FY 2023–24 is upto ₹2 crores, from filing annual return for the said financial year.

v) Notification No.15/2024-Central Tax dated 10th July, 2024

The above notification seeks to amend Notification No. 52/2018-Central Tax, dated 20th September, 2018, whereby the amount to be collected by electronic commerce operator is reduced from half per cent to 0.25 per cent, effective from 10th July, 2024.

B. NOTIFICATIONS RELATING TO RATE OF TAX

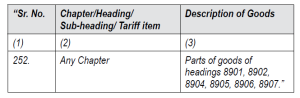

i) Notification No.2/2024-Central Tax (Rate) dated 12th July, 2024

The above notification seeks to amend Notification No 01/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 for changes in rates of taxes on some commodities like cartons, boxes, milk cans made of iron, steel, aluminium and solar cookers, etc.

ii) Notification No.3/2024-Central Tax (Rate) dated 12th July, 2024

The above notification seeks to amend Notification No. 02/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, which is regarding tax in relation to “pre-packaged and labelled” goods. The proviso is added in relation to agricultural farm produce.

iii) Notification No.4/2024-Central Tax (Rate) dated 12th July, 2024

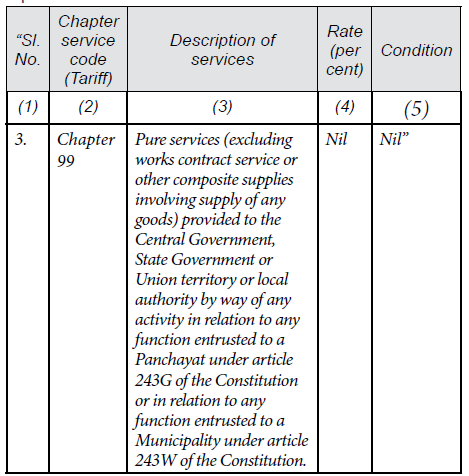

The above notification seeks to amend Notification No 12/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, which is regarding exempt services. Certain more services are added as well as other changes are made in the said notification.

C. CIRCULARS

Following circulars are issued by CBIC.

(i) Clarification about administrative changes – Circular no.223/17/2024-GST dated 10th July, 2024.

By above circular, administrative changes are made in relation to functions of proper officers under various sections of CGST Act like relating to Registration, etc.

(ii) Guidelines about recovery – Circular no.224/18/2024-GST dated 11th July, 2024.

By above circular, guidelines are given about recovery of outstanding dues during the period from disposal of first appeal till Appellate Tribunal comes into operation.

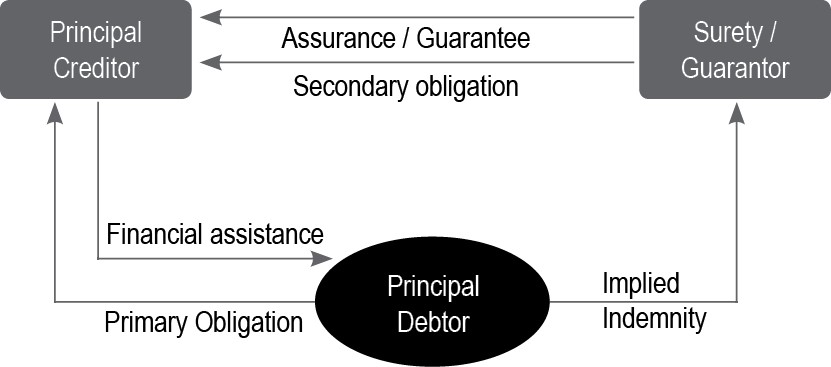

(iii) Clarification about Corporate Guarantee – Circular no.225/19/2024-GST dated 11th July, 2024.

By above circular, clarifications are given about issues relating to taxability and valuation of supply of services of providing corporate guarantee between related persons.

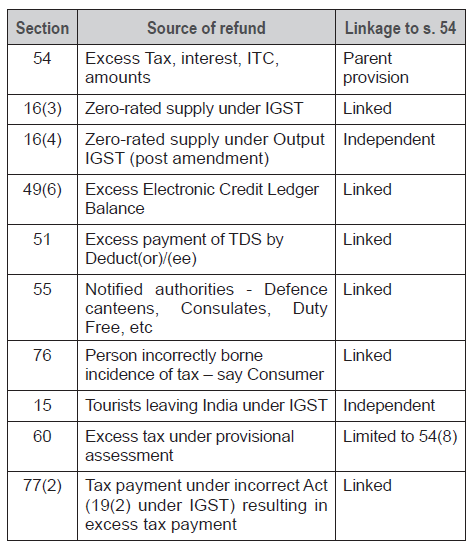

(iv) Clarification about additional refund – Circular no.226/20/2024-GST dated 11th July, 2024.

By above circular, mechanism for refund of additional IGST paid on account of upward revision in price of goods, subsequent to Export, is clarified.

(v) Clarification – Refund to CSD – Circular no.227/21/2024-GST dated 11th July, 2024.

By above circular, clarifications are given about processing of refund applications by Canteen Stores Department.

(vi) Clarification – GST on certain Services – Circular no.228/22/2024-GST dated 15th July, 2024.

By above circular, clarifications are given regarding applicability of GST on certain services like Indian Railway, RERA, BHIM-UPI transactions, General Life Insurance Schemes, Retrocession services and certain accommodation services, etc.

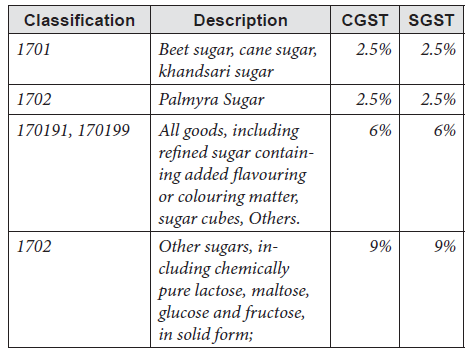

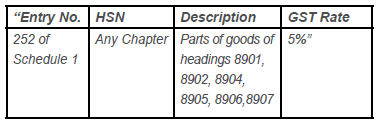

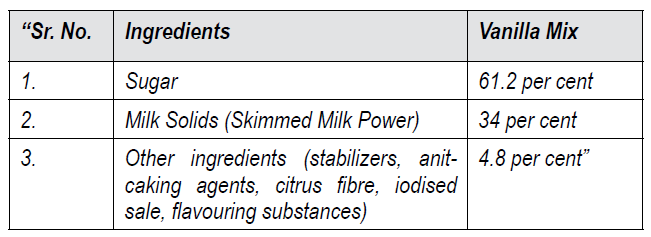

(vii) Clarification about Classification – Circular no.229/23/2024-GST dated 15th July, 2024.

By above circular, clarifications are given regarding GST rates and classification of goods based on recommendation of GST council in 53rd Meeting.

D. ADVANCE RULINGS

24. Health Care Services – Scope

M/s. Spandana Pharma (AR Order No.KAR ADRG-05/2024 dt. 29th January, 2024 (KAR)

The applicant is a Proprietorship Concern and engaged in the activity of providing health care services. The applicant also runs a hospital in the name of Spandana Pharma. Applicant sought to know ruling on following questions:

“i. Whether the supply of medicines, drugs and consumables used in the course of providing health care services to in-patients during the course of diagnosis and treatment during the patients admission in hospital would be considered as “Composite Supply” qualifying for exemption under the category of “health care services” as per Services Exempt Notification No.12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated: 28-06-2017 read with Section 8(a) of the CGST Act, 2017 / KGST Act, 2017?

ii. Whether the supply of food to in-patients would be considered as “Composite Supply” of health care services under CGST Act, 2017 & KGST Act, 2017 and consequently, can exemption under Services Exempt Notification No. 12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated: 28-06- 2017 read with Section 8(a) of GST be claimed?

iii. Retention Money: Whether GST is applicable on money retained by the applicant?

iv. Whether GST is exempt on Fees collected from nurses and psychologists for imparting practical training?”

Applicant explained that they are engaged in providing treatment to in-patients and outpatients suffering from psychic disorder, substance use disorder (addiction of drugs), neurology and other specialties.

The steps taken for curing the diseases were also explained.

The applicant referred to entry at sl.no.74 of Services Exemption Notification No.12/2017 Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, which reads as under:

| “Sl.

No. |

Chapter |

Description of Services |

Rate |

Condition |

| 74 |

Heading 9993 |

Services by way of:

(a) healthcare services by a clinical establishment, an authorised medical practitioner or paramedics:

(b) services provided by way of transportation of a patient in an ambulance, other

than those specified

in (a) above. |

NIL |

NIL |

The applicant also referred to the term “healthcare services” which is defined in Para 2 (zg) of Services Exemption Notification No. 12/2017 Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017.

The applicant submitted that it fulfils condition of being a clinical establishment as per definition of said term in para 2(zg) of Notification no.12/2017 dt. 28th June, 2017. The different SAC applicable to its services were stated as under:

SCS 9993 – Human Health and Social Care Services

SCS 99931 – Human Health Services

SCS 999311 – Inpatient services

The applicant submitted on its nature of services as under:

“The primary purpose of the hospital is to provide treatment to the patients approaching them. The basic Intention of the patients visiting the hospital is to get treatment for their ailment mainly mental disorder. Depending upon the severity of the illness the patient may require immediate medical attention, continuous monitoring etc. Therefore, according to their health condition they will be admitted in hospital as inpatient. The patients admitted to a hospital are treated with proper diagnosis of the disease / illness and treatment including appropriate medicines, surgical procedures if necessary, consumables required along with proper diet is administered to them in the most efficient manner so that they can regain their health within the shortest possible time and resume their activities. Therefore, the medicines, consumables and foods supplied in the course of providing treatment to the patients admitted in the hospital is an integral part of the health care service extended to the patients. Hence the room, medicines, consumables and food supplied in the course of providing treatment to the patients admitted in the hospital is undoubtedly naturally bundled in the ordinary course of business and the principal supply is health care service which is the predominant element of the composite supply and the other supplies such as room, medicines, consumables and food are incidental or ancillary to the predominant supply.”

The applicant also placed reliance on various Advance Rulings on similar facts like, in case of Malankar Orthodox Syrian Church Medical Mission Hospital reported in 2021 (53) G.S.T.L. 434 (A.A.R.-GST-Ker) and others.

Regarding question (B), applicant submitted that entry 74 of Services Exemption Notification No. 12/2017 Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 exempts healthcare service from payment of GST and healthcare services will be the predominant element of his composite supply, whereas medicines, surgical items, implants, stents and other consumables used in the course of providing such health care services to the inpatients are ancillary to it and does not itself become principal supply. In this respect, reliance was placed on definition of “composite supply” given in section 2(30) and “principal supply” given in section 2(90) of CGST Act. It was stressed that the tax liability on a composite supply shall be the rate of tax applicable on principal supply and since in its case, the principal supply of health care services is exempt from payment of tax, the supplies of other items ancillary to the principal supply of health care services are also exempt from payment of tax.

Accordingly, it was also submitted that supply of food to in-patients admitted to the hospital for medical treatment is a component of the composite supply and exempt along with the principal supply of healthcare services.

Regarding question (C), the applicant submitted that the term “Retention Money / charges” means those charges that are deducted by the hospitals while making payment to consultant doctors & technicians. It was explained that applicant invites consultant doctors with specialisation in mental health for diagnosing mental illness of patients and to suggest medicine, tests, rehabilitation, etc.

Based on para (5) in Circular No. 32/06/2018-GST dated 12th February, 2018, issued by Government of India, it was stated that the entire amount charged from the patient for payment to doctors and technicians towards health care services provided by the hospital is exempt from tax and hence, retention money is also exempt.

Regarding question (D), the applicant submitted that they provide practical training to nursing students and psychologists who are on the verge of completing course in recognised educational institutions. Nursing students and psychologists study theory in educational institutions, and applicant provides practical training to gain knowledge.

It was submitted that fees collected towards such training should be considered as exempt under entry no.74 of Notification no.12/2017-Central Tax (R) dated 28th June, 2017.

After considering above elaborate submission, the ld. AAR observed that the primary purpose of the hospital is to provide treatment to the patients approaching it, and the intention of the patients visiting the hospital is to get treatment for their ailment. Depending upon the severity of the illness and according to the health condition of the patient, they will be admitted to hospital as in-patient, observed the ld. AAR. The ld. AAR observed that different services are provided to the in-patients so that they can regain their health within the shortest possible time and resume their activities and therefore, the medicines, consumables and foods supplied in the course of providing treatment to the patients admitted in the hospital is an integral part of the health care service extended to the patients. All above are composite supply in relation to health care services and hence fall in exempted category, held the ld. AAR.

Regarding retention money, ld. AAR, following para (5) of Circular No. 32/06/2018-GST dated: 12th February, 2018, observed that entire amount charged by the hospital from the patients including the retention money and the fee / payments made to the doctors, etc., is towards the health care services provided by the hospital to the patients and accordingly exempt.

Regarding question (D), the ld. AAR observed that as per the meaning of “health care service” in definition of said term, it should be a service by way of diagnosis or treatment or care for illness, injury, deformity, abnormality or pregnancy. The ld. AAR held that the applicant is providing practical training to nursing students and psychologists, and hence, it is not covered under health care services. The ld. AAR determined the questions as under:

“i. The supply of medicines, drugs and consumables used in the course of providing health care services to in-patients during the course of diagnosis and treatment would be considered as ‘Composite Supply’ of health care services qualifying for exemption as per entry No. 74(a) of Notification No. 12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated: 28.06.2017 subjected to the condition mentioned therein.

ii. The supply of food to in-patients would be considered as ‘Composite Supply’ of health care services qualifying for exemption as per entry No. 74(a) of Notification No. 12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated: 28.06.2017 subjected to the condition mentioned therein.

iii. GST is not applicable on money retained by the applicant.

iv. GST is not exempted on the fees collected from nurses and psychologists for imparting practical training.”

25. Work without Civil Work vis-à-vis Works Contract

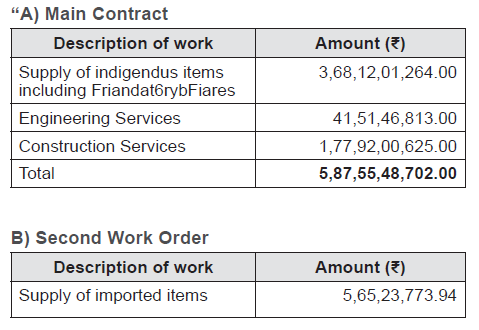

M/s. IDMC Limited (AR Order No. GUJ/ GAAAR/APPEAL/2023/08 (In App.No. Advance Ruling/SGST&CGST/2022/AR/02) dt. 7th December, 2023 (Guj)

The appellant has sought Advance Ruling on the following

questions:

“1. Whether contract involving supply of equipment/ machinery & erection, installation & commissioning services without civil work thereof would be contemplated as composite supply of cattle feed plant under GST regime. If the supplies would qualify as composite supply, what would be the classification of this bundle and applicable tax rate thereon in accordance with Notification No. 01/2017 – CT(Rate) dated June 28, 2017 (as amended).

2. Whether contract involving supply of equipment/ machinery & erection, installation & commissioning services with civil work thereof would be contemplated as works contract service or not. If the supplies would qualify as composite supply of works contract, what would be the classification and applicable tax rate thereon in accordance with Notification No.11/2017 – CT(Rate) dated June, 28, 2017 (as amended).?”

The ld. AAR decided the application vide Ruling No. GUJ/ GAAR/R/ 2022/14 dated 14th March, 2022 – 2022-VIL-92- AAR. This appeal is against above AR order.

The main contention of appellant was that they supply cattle feed plant, which includes equipment and machinery as well as erection and installation services thereof with or without civil work. The intention of the agreement in the present case is the supply and installation of cattle feed plant, and this arrangement does not include any civil work / services. It was further case of appellant that it qualifies to be composite supply; but not “works contract service”; since, as per the definition of works contract, erection, fitting out, etc. should be carried out for an immovable property. Appellant cited AR in their own case having similar facts, bearing no. GUJ/GAAR/ REFERENCE /2017-18/1, where it is held that contract without civil work would not be contemplated as works contract. Other rulings also relied upon.

It was contended that the Contract was thus for supply of cattle feed plant along with services and would qualify as composite supply and would be classifiable under the heading 8436 attracting GST @12 per cent. The ld. AAR had ruled as under:

“Supply of a functional Cattle Feed Plant, inclusive of its Erection, Installation and Commissioning and related works involved for both the question 1 & 2, is Works Contract Service Supply, falling at SAC 998732 attracting GST at 18%.”

The appellant reiterated its contentions and also cited further authorities before the ld. AAAR.

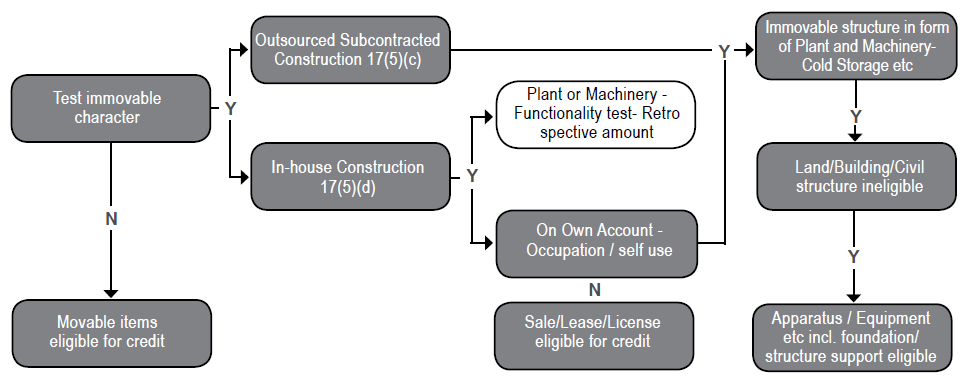

The ld. AAAR observed that due to Clause 6 of Schedule II of CGST Act 2017, Works Contract is a composite supply and same is treated as supply of services.

The ld. AAAR also referred to term “works contract” defined in Section 2(119) of CGST Act,2017 as below:

“‘works contract’ means a contract for building, construction, fabrication, completion, erection installation, fitting out, improvement, modification, repair, maintenance, renovation, alteration or commissioning of any immovable property wherein transfer of property in goods (whether as goods or in some other form) is involved in the execution of such contract.”

The ld. AAAR further observed that the term “immovable property” is not defined under GST law, but Section 3(26) of the General Clauses Act says “immovable property” shall include land, benefits to arise out of land, and things attached to the earth, or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth.

The ld. AAAR referred to photographs submitted by appellant and reproduced the same in the appeal order.

The ld. AAAR observed that as per appellant, they have following responsibilities with respect to plant execution:

“(i) Supply of cattle feed equipment such as pellet mill, hammer mill, etc.

(ii) Supply of other ancillary equipment / goods such as MS Structural, MS Chequered plates, Conveyors for transporting raw material in the plant, Electrical switch boards and cables etc.

(iii) Services relating to commission, installation and erection of equipment.

(iv) Undertaking trial runs on the machinery installed and testing of output received.”

The ld. AAAR further observed that, from the photographs and details, of supplies made, the various equipments assembled by the appellant at the customer’s premises are either fitted with foundation / structures or fitted on foundation / structures, and the said cattle feed plant set up at customer’s premises cannot be shifted from one place to another without dismantling of all the equipments, machine parts and accessories and electrical systems. Therefore, the ld. AAAR observed that the cattle feed plant supplied involves supply of goods as well as services like installation, erection and commissioning of the plant, and it fulfils the criteria of an “immovable property” as it is attached to the earth or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth.

The ld. AAAR referred to various case laws on subject and also peculiar facts noted by ld. AAR in its order. Considering the above, the ld. AAAR dismissed the appeal confirming order of ld. AAR.

26. Classification – “Tree Pruners”

M/s. Global Marketing (AR Order No. KAR ADRG-02/2024 dt. 29th January, 2024 (Kar)

The applicant is a Partnership firm and engaged in the business activity of buying and selling of product called “Tree Pruners”. The product essentially consists of a pole which can be extendable in length and fitted with a knife, which is used in agricultural activities such as harvesting the crops of areca, pepper and coconut and also in spraying pesticide.

The appellant has sought advance ruling in respect of the

following questions:

“a) Whether the tree pruners covered by HSN Code 82016000 relates to Agricultural implements manually operated or animal driven i.e. hand tools, such as spades, shovels, mattocks, picks, hoes, forks and rakes, axes, bill hooks and similar hewing tools; secateurs and ‘pruners of any kind’; scythes, sickles, hay knives, hedge shears, timber wedges and other tools of a kind used in agriculture, horticulture or forestry other than Ghamella.

b) Whether the supply of Agriculture Hand Tools i.e., Tree Pruners to farmer is exempt from the CGST/ SGST/IGST Act.”

The applicant explained that the said product is made, predominantly, out of raw material “aluminium”, and hence, the probable classifications would be either based on the usage or based on the raw material, i.e., articles of aluminium. The contention of the applicant was that since it has a knife, it cannot be used for any general purpose, but it can be used by farmers for harvesting the crops of areca, pepper and coconut and used in spraying pesticide.

The other aspects like, it is seasonal and entitled for a subsidy from the Horticulture Department, was also brought to the notice of ld. AAR.

It was submitted that “Tree Pruners” are agricultural implements and hence in common parlance, it can be regarded as a tool, which is used in agriculture, specifically in relation to harvesting coconut, areca and pepper. Hence, the product merits classification as an “agricultural implements / tool used in agriculture” under Tariff Heading 8201 9000 and accordingly exempt.

The ld. AAR referred to Chapter 82 of the Customs Tariff and further Tariff Heading 8201 60 00 which covers “Hedge shears, two-handed pruning shears and similar two-handed shears Products.”

The ld. AAR observed that the product in question, i.e., “Tree Pruner” is a manually operated agricultural implement and hence qualified to be a tool of a kind used in agriculture. The ld. AAR further observed that “pruners of any kind” finds specific mention in the description of entry at Sl. no. 137 and, therefore, the aforesaid exemption is squarely applicable to the product under consideration.

Accordingly, AAR passed order, holding that the supply of Tree Pruners is exempted vide Entry No. 137 of Notification No. 2/2017 – Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017.

27. Renting of Residential dwelling – Scope

Ms. Deeksha Sanjay, proprietrix, M/s. Deeksha Sanjay (AR Order No. KAR ADRG-34/2023 dt. 16th November, 2023 (Kar)

The applicant is a proprietary concern, registered under the GST Act, engaged in the business of renting of residential dwelling, situated at #14, 2nd Cross, Thimmappa Reddy Layout, Bengaluru-560076. Being the owner of the said property, applicant pays property tax to the BBMP, and the said building is suitable for residential purposes, and it is sanctioned for usage as residential building.

The applicant has sought advance ruling in respect of the following questions:

“a. Whether renting of residential dwelling to the students and working women for residential purpose along with amenities and facilities such as food, furniture, appliance, cleaning, security, pest control etc., on monthly rental basis, is exempt under entry No. 12 of Notification No. 12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017 or not?

b. If applicant transaction is not exempt, then what is the GST rate?

c. If applicant transaction is taxable, whether applicant can claim ITC on input used for providing taxable service?”

Amongst others, applicant provides services like cot with mattress, table with chair and cupboard with locking facility, one light and one fan per room and attached bathroom, breakfast, lunch, dinner and evening tea / snacks, laundry, power backup, house-keeping, security and RO drinking water.

The applicant explained that it provides residential dwelling to the students and working women on monthly rental basis; the services involve basic residential facilities required for staying and study which include well- maintained furnished residence, light, water, etc.,

Applicant provides the following three types of renting services on monthly rental basis according to the option of the students / women:

“a) Single Occupancy: A unit in residential dwelling which contains single bed in a room for single person, having facilities of electricity, food, furnishing, fan, lighting etc.,

b) Double Occupancy: A unit in residential dwelling that contains two beds in a room for two persons, having facilities of electricity, food, furnishing, fan, lighting etc., dual occupancy is a great way to save money, normally this option is chosen by one or more friends/relatives who are familiar with each in study. If empty units available then from dual occupancy to occupancy can be opted by residents.

c) Triple Occupancy: A unit in residential dwelling that contains three beds in a room for three persons, having facilities of electricity, food, furnishing, fan, lightings etc., Student who generally wish to study in a group will choose this option.”

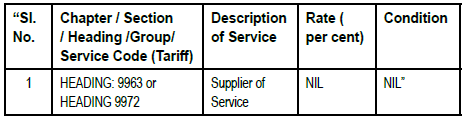

Citing relevant provisions of law, the submission of applicant was that the services by way of renting of residential dwelling for use as residence are covered under SAC 9963 or 9972 and exempted by entry 12 of Notification 12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 read with Notification 04/2022-Central Tax (Rate) dated 13th July, 2022. It was tried to impress that contract for renting of residential dwelling along with facilities is a composite supply of renting service, the Principal Supply is renting of residential dwelling, other facilities are incidental to the renting of dwelling unit, and hence exempt as above. Meanings of “residential”, “dwelling”, etc., were cited.

In this regards, the ld. AAR referred to relevant entries of Notification No. 12/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and reproduced as under:

| “Sl.

No. |

Chapter, Section, Heading, Group or Service Code (Tariff) |

Description of Services |

Rate (per cent) |

Condition |

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

| 12 |

Heading 9963

or Heading 9972 |

Services by way of renting of residential dwelling for use as residence [except where the residential dwelling is rented to a registered person]. |

NIL |

NIL |

|

|

[Explanation. – For the purpose of exemption under this entry, this entry shall cover services by way of renting of residential dwelling to a registered person where: |

|

|

|

|

(i) the registered person is proprietor of a proprietorship concern

and rents the residential dwelling in his personal capacity for use as

his own residence; and Heading 9963 or Heading 9972 |

|

|

|

|

(ii) such renting is |

|

|

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

|

on his own account and not that of the

proprietorship concern.] |

|

|

| 14 |

Heading 9963 |

Services by a hotel, inn, guest house, club or campsite, by whatever name called, for residential or lodging purposes, having declared tariff of a unit of accommodation below one thousand rupees per day or equivalent.” |

NIL |

NIL |

The ld. AAR also observed that entry at Sl. No. 14 is omitted vide Notification No.4/2022 dated 13th July, 2022 and thus in effect, only services by way of renting of residential dwelling for use as residence are exempted from GST. Services by a hotel, an inn, a guest house, a club or a campsite by whatever name called, for residential or lodging purposes, even when below ₹1,000 are liable to GST w.e.f. 18th July, 2022.

Referring to terms about rent, unit and offer of accommodation in service agreement, the ld. AAR observed as under:

“From the above it is evident that the resident/inhabitants are offered a unit i.e. a portion of a room with a cot on monthly rental basis. Further, monthly rent also is charged and collected for the unit only but not for the residential dwelling. Thus, the impugned accommodation being provided does not qualify to be a residential dwelling. Further it is seen that units are shared by one or more unrelated inhabitants. Applicant charges all the inhabitants of a room individually and not for a room as a whole. It is apparent from the above that the accommodation provided to each of the inhabitant is not a residential dwelling but a cot / a unit in the room; un-related people share the said room and invoices are raised per bed on monthly basis are not characteristic of a residential dwelling.

Further, it is also an admitted fact that the accommodation being provided by the applicant, out of the immovable property claimed as residential dwelling, does not have individual kitchen facility to each of the inhabitant and also cooking of food by inhabitants is not allowed, which are an essential characteristic for any permanent stay. On this count as well, the impugned accommodation being provided does not qualify to be a residential dwelling and thus the question of using the same as residence does not arise.”

The reliance of the applicant on judgment of Hon’ble High Court of Karnataka in the case of Taghar Vasudeva Ambarish (WP No.14891 of 2020 (T-Res) dated 7th February, 2022) – 2022-VIL-110-KAR was differed by the ld. AAR on the grounds that it is appealed before Hon. Supreme Court as well as on grounds that facts are different. The ld. AAR held the activity taxable and determined rate @ 12 per cent in terms of entry number 7(1) of Notification no.11/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, as amended. The ld. AAR also held that applicant is entitled to ITC as per law.

28. GST Liability on Canteen recovery

M/s. Tube Investment of India Ltd. (AR Order No.12(A)/2023-24 in App. No.07/2022-23 dt. 22nd December, 2023 (Uttarakhand)

The background facts are that originally, appellant applied for ruling on certain questions.

The ld. AAR vide its order in 12/2022-23 dt. 24th November, 2022 ruled as under:

“a. Whether the nominal amount of recoveries made by the Applicant from the employees who are provided food in the factory canteen would be considered as a ‘Supply’ by the applicant under the precisions of Section 7 of Central Goods and Service Tax Act, 2017 – Yes, it is a supply.

b. Whether GST is applicable on the amount recovered from the employees for the food provided in the factory canteen or on the amount paid by the Applicant to the Canteen Service Provider – GST is applicable on both the amount i.e. amount paid to the canteen service provider and also on the nominal amount recovered from the employees.

c. Whether input tax credit (ITC) is available on GST charged by the Canteen Service Providers for providing the catering services at the factory where it is obligatory for the Applicant to provide the same to its employees as mandated under the Factories Act, 1948, even if the answer to question (a) is ‘No’? – Benefit of ITC is not admissible on the GST on the amount paid to the canteen service providers and also on the amount recovered from the employees.

d. Whether input tax credit (ITC) can be availed on GST charged by the Canteen service providers, the answer to the question (b) is ‘Yes’? – No, ITC is not admissible on the GST on the amount paid to the canteen service providers.”

Not satisfied with the ruling of the advance ruling, an appeal was filed before the Appellate Authority for Advance Ruling, Goods & Service Tax, Uttarakhand. The ld. AAAR decided appeal vide Order No. 05/2022-23 dated 13th March, 2023.

The ld. AAAR remanded matter back to ld. AAR to determine application afresh taking cognisance of CBIC Circular No.172/04/2022-GST dated 6th July, 2022. Therefore, this fresh ruling.

The ld. AAR observed that the applicant is a leading engineering company engaged in manufacture of precision steel tubes, etc., and in a factory in the state of Uttarakhand, more than 500 workmen (both direct and indirect) are employed. It is also noted that the applicant recovers nominal amount from the employees on a monthly basis to provide food to them and for same, they have engaged contractors, who operate canteen within the factory premises. It is also noted that the applicant discharges GST @5 per cent on the taxable value which is sum total of the cost of the canteen service provider plus 10 per cent notional mark up. Further, the applicant does not avail input tax credit (ITC) on the expenses incurred on the services provided by the canteen service provider, and it is absorbed as a cost in the books of accounts.

The ld. AAR observed that the clarification is sought as to whether GST is liable to be paid on that part of the amount which is collected from their employees towards provision of food and also whether ITC is available on the GST paid by them on the taxable value of the canteen service. The ld. AAR observed that the contention of applicant is based on premises that the supply of food in canteen is part of employment contract and hence ousted from the scope of supply vide the Entry 1 in Schedule III of the CGST Act, 2017. Therefore, there is no supply between the Applicant and the employees. Further, the amount received from the employees is in the nature of recovery and not consideration.

As per direction of ld. AAAR in appeal order, the ld. AAR referred to Circular no.172/04/2022-GST dt. 6th July, 2022 and particularly to clarification given at Sl. No.5 in said circular.

The ld. AAR observed that as per the said circular, perks provided in terms of contractual agreement are not supply under GST which means that if any perks are provided to the employee, in terms of contractual agreement, then such perks are outside the purview of GST.

The ld. AAR observed that if any perk / privilege is mentioned in the employment contract, then it becomes binding for the employer to provide the same to the employees but anything provided beyond the employment contract is a part of sweet will or largesse on the part of employer and cannot be insisted upon by an employee.

The ld. AAR found that consuming food at the canteen facility made available by the applicant in their premises is not mandatory and it is purely optional for the employees and that while extending the canteen facility, no meal is extended free but the meals / food are provided at concessional rates.

The ld. AAR observed that although the provision of food in canteen is on account of the mandate prescribed in the Factories Act, 1948, the supplies are provided by the employer to the employees for a consideration, though nominal. The ld. AAR held that it is taxable supply.

Referring to provisions of Factories Act, 1948, the ld. AAR also held that such supply is in course of business, being incidental to business activity of applicant.

The further contention that making recovery is not consideration but recovery of cost also negatived by the ld. AAR on grounds that such recovery fulfils the definition of “consideration” given in section 2(31) of CGST Act.

In relation to availability of ITC, the ld. AAR observed as under:

“So in the instant case, the flow of the transaction is that the Canteen Contractor is providing service to the applicant, which is classifiable as Restaurant Service and the applicant himself is also providing same service to its worker, as mandated in the Factories Act, 1948 i.e. he is also providing a Restaurant Service to its worker. As already brought out above, the Restaurant Service, compulsorily attracts GST rate of 5% without ITC, in a non-specified premises and the applicant’s premises is not a specified premises in terms of Notification No. 11/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017. Therefore, though the Section 17(5) of the CGST Act, 2017, does not debar availment of ITC in entirety, but in the present case availment of ITC is debarred in terms of provisions of Notification No. 11/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017 as amended vide Notification No. 20/2019- C.T. (Rate) dated 30.09.2019.”

In respect of all above issues, the ld. AAR also relied upon order in appeal passed by the ld. AAAR, H.P.

The ld. AAR accordingly ruled that recoveries in canteen for foods are taxable supply and no ITC is eligible.