Background

IAS 12 (Ind AS 12) Income

Taxes specifies requirements for

current and deferred

tax assets and

liabilities. However, there was no

clarity with respect to recognition and

measurement of uncertain

tax treatments. An‘uncertain tax treatment’

is a tax treatment for which there is uncertainty over whether the relevant

taxation authority will accept the entity’s tax treatment under tax law. For

example, an entity’s

decision not to include

particular income in taxable profit,

is an uncertain tax treatment if its acceptability is

uncertain under tax

law. IFRIC 23 Uncertainty over Income Tax

Treatments is an interpretation of IAS 12 that deals with recognition and

measurement of uncertain tax treatments. A corresponding interpretation is not

yet issued under Ind AS, but is expected shortly.

Uncertainty over Income Tax Treatments

In assessing whether

uncertainty over income tax treatments exists, an entity may consider a number

of indicators including, but not limited to, the following:

– Ambiguity in the drafting of relevant tax

laws and related guidelines (such as ordinances, circulars and letters) and

their interpretations

– Income tax practices that are generally

applied by the taxation authorities in specific jurisdictions and situations

– Results of past examinations by taxation

authorities on related issues

– Rulings and decisions from courts or other

relevant authorities in addressing matters with a similar fact pattern

– Tax memoranda prepared by qualified in-house

or external tax advisors

– The quality of available documentation to

support a particular income tax treatment.

Unit of Account

The Interpretation requires

an entity to determine whether to consider each uncertain tax treatment

separately or together with one or more other uncertain tax treatments. This

determination is based on which approach better predicts the resolution of the

uncertainty. In determining the approach that better predicts the resolution of

the uncertainty, an entity might consider, for example, (a) how it prepares its

income tax filings and supports tax treatments; or (b) how the entity expects

the taxation authority to make its examination and resolve issues that might

arise from that examination.

The author believes that

interdependent tax positions (i.e., where the outcomes of uncertain tax

treatments are mutually dependent) should be considered together. Significant

judgement may be required in the determination of the unit of account. In

making the judgement, entities would need to consider the approach expected to

be followed by the taxation authorities to resolve the uncertainty. The

judgement required in the selection of a unit of account may be particularly

challenging in groups of entities trading in various jurisdictions where the

relevant tax laws or taxation authority treat similar elements differently.

Example 1 – Unit of account

Entity A is part of a

multinational group and provides intra-group loans to affiliates. It is funded

through equity and deposits made by its parent. Whilst the entity can show that

its interest margin earned on many loans is at an appropriate market rate,

there are loans where the rate is open to challenge by the taxation

authorities. However, Entity A determines that, across the loan portfolio as a

whole, the existence of rates above and below a market comparator results in an

overall interest margin that is within a reasonable range accepted by the

taxation authorities.

Depending on the applicable

tax law and practice in a specific jurisdiction, a taxation authority may accept

a tax filing position on the basis of the overall interest margin if it is

within a reasonable range. However, there might be other taxation authorities

that would examine the interest rate separately for each loan receivable. In

considering whether uncertain tax treatments should be considered separately

for each loan receivable or combined with other loan receivables, Entity A

should adopt the approach that better reflects the way the taxation authority

would examine and resolve the issue.

Detection risk

The Interpretation requires

an entity to invariably assume that a taxation authority will examine amounts

it has a right to examine and have full knowledge of all related information

when making those examinations.

In some jurisdictions,

examination by taxation authorities is subject to a time limit, sometimes

referred to as a statute of limitations. In others, examination by taxation

authorities might not be subject to a statute of limitations, which means the

authorities can examine the amounts at any time in the future. Some respondents

to the draft Interpretation suggested in their comment letter that an

assessment of the probability of examination would be relevant in this latter

case. However, the IFRS Interpretation Committee (IC) decided not to change the

examination assumption, nor to create an exception to it, for circumstances in

which there is no time limit on the taxation authority’s right to examine

income tax filings.

The IC also noted that the

assumption of examination by the taxation authority, in isolation, would not

require an entity to reflect the effects of uncertainty. The threshold for

reflecting the effects of uncertainty is whether it is probable that the

taxation authority will accept an uncertain tax treatment. In other words, the

recognition of uncertainty is not determined based on whether a taxation

authority examines a tax treatment.

The Interpretation does not

explain what is meant by ‘results of examinations’. The examination procedures

vary by jurisdiction and, in some jurisdictions, an examination can have

multiple phases. In the author’s view, the communication between an entity and

the taxation authorities during the course of such examinations may provide

relevant information that could give rise to a change in facts and

circumstances before the actual ‘results’ of the examination are formally issued.

Example 2 – Detection risk

Entity A is based in

Country B. It is generally known that the taxation authorities in Country B

have limited resources. As a consequence, their examination procedures are

usually limited to a summary assessment of the income tax filings. Scrutiny tax

examinations are only performed in very rare circumstances and if there is a

clear indication of a tax fraud. Entity A has never been subjected to such a

scrutiny examination by the taxation authorities.

Prior to the application of

IFRIC 23, Entity A argued that it was unlikely that the taxation authorities

would identify any key income tax exposures not already identified through

their summary assessment, because they could be identified only by analysing

the underlying accounting records. Therefore, Entity A did not recognise any

uncertain tax treatments.

With the adoption of IFRIC

23, Entity A would need to consider underlying tax positions even though

scrutiny by the taxation authorities is unlikely. Entity A should assume that

the taxation authority can and will examine amounts it has a right to examine

and have full knowledge of all related information when making those

examinations.

Recognition and Measurement

Under IFRIC 23, the key

test is whether it’s probable that the taxation authority would accept the tax

treatment used or planned to be used by the entity in its income tax filings.

If yes, then the amount of taxes recognised in the financial statements would

be consistent with the entity’s income tax filings. Otherwise, the effect of

uncertainty should be estimated and reflected in the financial statements. This

would require the exercise of judgement by the entity. The recognition of

current and deferred taxes including uncertain tax treatments continues to be

on the underlying principle of “probability”. The measurement requirements in

IFRIC 23 do not distinguish between a probability of 51% and a probability of

100%. This is consistent with the objective of IAS 12 (Ind AS 12) that refers

to a probable threshold and with the Conceptual Framework for Financial

Reporting which refers to a probability threshold for the recognition of

assets and liabilities in general. It should be noted that deferred tax assets

on carry forward of losses can be recognised only if there is convincing

evidence that it will be utilised in future years.

Example 3 – Current and deferred tax impact

Entity C, constructs and

leases wooden chalet at hill stations, and claims 100% depreciation on the

basis that they are temporary structures. However, the tax laws may not

consider them as temporary structures and therefore there is a risk that the

100% depreciation claim may be disallowed. On application of IFRIC 23, Entity C

should reflect the impact of such uncertainties in the measurement of current

and deferred tax assets and liabilities as at the reporting date.

An entity may need to apply

judgement in concluding whether it is probable that a particular uncertain tax

treatment will be acceptable to the taxation authority. An entity may consider

the following:

– Past experience related to similar tax

treatments

– Legal advice or case law related to other

entities

– Practice guidelines published by the taxation

authorities

– The entity obtains a pre-clearance from the

taxation authority on an uncertain tax treatment.

In defining ‘uncertainty’,

the entity only needs to consider whether a particular tax treatment is probable,

rather than highly likely or certain, to be accepted by the taxation

authorities. If an entity concludes it is probable that the taxation authority

will accept an uncertain tax treatment, the entity shall determine the taxable

profit or loss, deferred taxes, unused tax losses, unused tax credits or tax

rates consistently with the tax treatment used or planned to be used in its

income tax filings. If an entity concludes it is not probable that the taxation

authority will accept an uncertain tax treatment, the entity shall reflect the

effect of uncertainty in determining the related taxable profit or loss,

deferred taxes, unused tax losses, unused tax credits or tax rates. An entity

shall reflect the effect of uncertainty for a unit of uncertain tax treatment

by using either of the following methods, depending on which method the entity

expects to better predict the resolution of the uncertainty:

a) the

most likely amount—the single most likely amount in a range of possible

outcomes. The most likely amount may better predict the resolution of the

uncertainty if the possible outcomes are binary or are concentrated on one

value.

b) the

expected value—the sum of the probability-weighted amounts in a range of

possible outcomes. The expected value may better predict the resolution of the

uncertainty if there is a range of possible outcomes that are neither binary

nor concentrated on one value.

If an uncertain tax

treatment affects current tax and deferred tax (for example, if it affects both

taxable profit used to determine current tax and tax bases used to determine

deferred tax), an entity shall make consistent judgements and estimates for

both current tax and deferred tax.

Example 4 – Application of Expected Value Method

– Entity A’s income tax filing in a

jurisdiction includes deductions related to transfer pricing. The taxation

authority may challenge those tax treatments.

– Entity A

notes that the taxation authority’s decision on one transfer pricing matter

would affect, or be affected by, the other transfer pricing matters. Entity A

concludes that considering the tax treatments of all transfer pricing matters

in the jurisdiction together better predicts the resolution of the uncertainty.

Entity A also concludes it is not probable that the taxation authority will

accept the tax treatments. Consequently, Entity A reflects the effect of the

uncertainty in determining its taxable profit.

– Entity A estimates the probabilities of the

possible additional amounts that might be added to its taxable profit, as

follows:

|

|

Estimated additional amount, INR

|

Probability, %

|

Estimate of expected value, INR

|

|

Outcome 1

|

–

|

15%

|

–

|

|

Outcome 2

|

200

|

5%

|

10

|

|

Outcome 3

|

400

|

20%

|

80

|

|

Outcome 4

|

600

|

10%

|

60

|

|

Outcome 5

|

800

|

30%

|

240

|

|

Outcome 6

|

1,000

|

20%

|

200

|

|

|

|

100%

|

590

|

– Outcome 5 is the most likely outcome.

However, Entity A observes that there is a range of possible outcomes that are

neither binary nor concentrated on one value. Consequently, Entity A concludes

that the expected value of INR 590 better predicts the resolution of the

uncertainty.

– Accordingly, Entity A recognises and measures

its current tax liability that includes INR 650 to reflect the effect of the

uncertainty. The amount of INR 590 is in addition to the amount of taxable

profit reported in its income tax filing.

Example 5 – Application of the Most Likely Outcome Method

– Entity B acquires for INR 100 a separately

identifiable intangible asset that has an indefinite life and, therefore, is

not amortised applying IAS 38 (Ind AS 38) Intangible Assets. The tax law

specifies that the full cost of the intangible asset is deductible for tax

purposes, but the timing of deductibility is uncertain. Entity B concludes that

considering this tax treatment separately better predicts the resolution of the

uncertainty.

– Entity B deducts INR 100 (the cost of the

intangible asset) in calculating taxable profit for Year 1 in its income tax

filing. At the end of Year 1, Entity B concludes it is not probable that the

taxation authority will accept the tax treatment. Consequently, Entity B

reflects the effect of the uncertainty in determining its taxable profit and

the tax base of the intangible asset. Entity B concludes the most likely amount

that the taxation authority will accept as a deductible amount for Year 1 is

INR20 and that the most likely amount better predicts the resolution of the

uncertainty.

– Accordingly, in recognising and measuring its

deferred tax liability at the end of Year 1, Entity B calculates a taxable

temporary difference based on the most likely amount of the tax base of INR 80

(INR 100 – INR 20) to reflect the effect of the uncertainty, instead of the tax

base calculated based on Entity B’s income tax filing (INR 0).

– Entity B reflects the effect of the

uncertainty in determining taxable profit for Year 1 using judgements and

estimates that are consistent with those used to calculate the deferred tax

liability. Entity B recognises and measures its current tax liability based on

taxable profit that includes INR 80 (INR 100 – INR 20). The amount of INR80 is

in addition to the amount of taxable profit included in its income tax filing.

This is because Entity B deducted INR 100 in calculating taxable profit for

Year 1, whereas the most likely amount of the deduction is INR 20.

Changes in facts and circumstances

An entity shall reassess a

judgement or estimate required by this Interpretation, if the facts and circumstances

on which the judgement or estimate was based change or as a result of new

information that affects the judgement or estimate. For example, a change in

facts and circumstances might change an entity’s conclusions about the

acceptability of a tax treatment or the entity’s estimate of the effect of

uncertainty, or both. An entity shall reflect the effect of a change in facts

and circumstances or of new information as a change in accounting estimate

applying IAS 8 (Ind AS 8) Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting

Estimates and Errors. An entity shall apply IAS 10 (Ind AS 10) Events

after the Reporting Period to determine whether a change that occurs after the

reporting period is an adjusting or non-adjusting event.

Examples of changes in

facts and circumstances or new information that, depending on the

circumstances, can result in the reassessment of a judgement or estimate

required by this Interpretation include, but are not limited to, the following:

(a) examinations

or actions by a taxation authority. For example:

(i) agreement

or disagreement by the taxation authority with the tax treatment or a similar

tax treatment used by the entity;

(ii) information

that the taxation authority has agreed or disagreed with a similar tax

treatment used by another entity; and

(iii) information

about the amount received or paid to settle a similar tax treatment.

(b) changes

in rules established by a taxation authority.

(c) the

expiry of a taxation authority’s right to examine or re-examine a tax

treatment.

Example 6 – Change in facts and circumstances

Entity A claimed a

tax-deduction for a particular expense item. In the prior year, Entity A had

concluded that it was probable that the taxation authority would accept the tax

deduction. However, during the current year, Entity A is alerted by a similar

issue where a tax deduction was denied in a ruling by the Supreme Court. The

recent court ruling is considered a change in facts and circumstances. As a

result, Entity A has to reassess the uncertain tax treatment, taking into

account the recent Supreme Court decision.

Example 7 – Events after the reporting date

Scenario A

Entity C had claimed a tax

deduction for a particular expense item in its tax return related to the

financial year ending 31st December 2018. However, for the purpose

of recognising current and deferred taxes in that year, Entity C had concluded

that it is not probable that the taxation authorities will accept the tax

deduction. Accordingly, Entity C had recognised an additional tax liability

relating to the uncertainty. In February 2020, before the approval of the

financial statements for the year ending 31st December 2019, Entity

C receives the final tax assessment for 2018. The tax assessment confirms the

full deductibility of the expense item. The confirmation of tax deduction

received after the reporting period and prior to authorisation of the financial

statements for 2019 is considered as an adjusting event after the reporting

period. Accordingly, the additional tax liability that was recognised in 2018

relating to the uncertainty is released in the 2019 period.

Scenario B

Entity B claimed a

tax-deduction pertaining to interest expense on a loan granted by an affiliated

company, amounting to INR 500,000 in its tax return related to the financial

statements for the year ending 31st December 2018. However, for the

purposes of recognising current and deferred taxes for that year, Entity B had

concluded that the taxation authorities will only accept a deduction of INR 100,000.

In March 2020, before the approval of the financial statements for the year

ending 31st December 2019, Entity B learns from its tax advisor that

the taxation authorities have confirmed that they will accept, on a

retrospective basis, another method of determining interest rate at arm’s

length that would lead to a tax deduction of INR 300,000 in year 2018. In this

example, it appears that the taxation authorities have issued a new guideline

on deductibility of interest expenses relating to a loan from an affiliated

company. Accordingly, in contrast to Scenario A above, the information received

in March 2020 is considered as a non-adjusting event after the reporting period

for the 2019 financial statements.

Absence of an explicit

agreement or disagreement by the taxation authorities on its own is unlikely to

represent a change in facts and circumstances, or new information that affects

the judgements and estimates made. In such situations, an entity has to

consider other available facts and circumstances before concluding that a

reassessment of the judgements and estimates is required.

An uncertain tax treatment

is resolved when the treatment is accepted or rejected by the taxation

authorities. The Interpretation does not discuss the manner of acceptance

(i.e., implicit or explicit) of an uncertain tax treatment by the taxation

authorities. In practice, a taxation authority might accept a tax return

without commenting explicitly on any particular treatment in it. Alternatively,

it might raise some questions in an examination of a tax return. Unless such

clearance is provided explicitly, it is not always clear if a taxation

authority has accepted an uncertain tax treatment. An entity may consider the

following to determine whether a taxation authority has implicitly or

explicitly accepted an uncertain tax treatment:

– The tax treatment is explicitly mentioned in

a report issued by the taxation authorities following an examination

– The treatment was specifically discussed with

the taxation authorities (e.g., during an on-site examination) and the taxation

authorities verbally agreed with the approach; or

– The treatment was specifically highlighted in

the income tax filings, but not subsequently queried by the taxation

authorities in their examination.

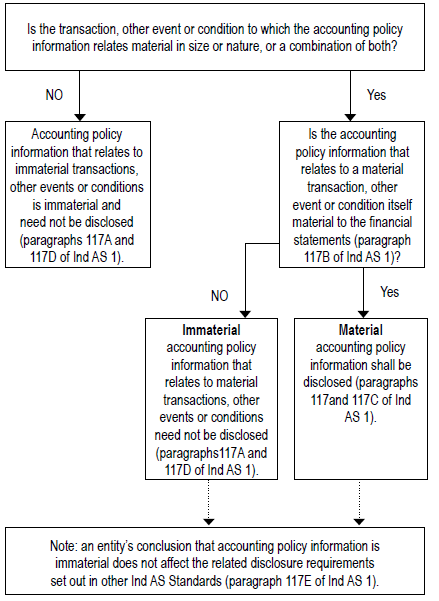

Disclosures

There are no new disclosure

requirements in IFRIC 23. However, entities are reminded of the need to

disclose, in accordance with existing IFRS (Ind AS) standards. When there is

uncertainty over income tax treatments, an entity shall determine whether to

disclose: judgements made in determining taxable profit (tax loss), tax bases,

unused tax losses, unused tax credits and tax rates; and information about the

assumptions and estimates made in determining taxable profit (tax loss), tax

bases, unused tax losses, unused tax credits and tax rates under IAS 1 (Ind AS

1) Presentation of Financial Statements. If an entity concludes it is

probable that a taxation authority will accept an uncertain tax treatment, the

entity shall determine whether to disclose the potential effect of the

uncertainty as a tax-related contingency under IAS 12 (Ind AS 12).

Effective date and transition

IFRIC 23 applies to annual

reporting periods beginning on or after 1st January 2019. Earlier

application is permitted. Entities can apply the Interpretation using either of

the following approaches:

– Full retrospective approach: this approach

can be used only if it is possible without the use of hindsight. The

application of the new Interpretation will be accounted for in accordance with

IAS 8, which means comparative information will have to be restated; or

– Modified retrospective approach: no

restatement of comparative information is required or permitted under this

approach. The cumulative effect of initially applying the Interpretation will

be recognised in opening equity at the date of initial application, being the

beginning of the annual reporting period in which an entity first applies the

Interpretation.

It

is not clear as to when this interpretation will apply under Ind AS. It is most

likely that this Interpretation may apply from annual reporting periods

beginning on or after 1st April 2019.

Key challenges

– Applying the Interpretation could be

challenging for entities, particularly those that operate in more complex

multinational tax environments.

– It would be challenging for entities to

estimate the income tax due with respect to tax inspections, when tax

authorities examine different types of taxes together and issue a report with a

single amount due therein.

– Entities may also need to evaluate whether

they have established appropriate processes and procedures to obtain

information, on a timely basis, that is necessary to apply the requirements in

the Interpretation and make the required disclosures.

– IFRIC 23 requires an entity to assume a

detection risk of 100%. An entity should not take any credit for the

possibility that uncertain tax treatments could be overlooked by the taxation

authority. This is a different approach compared to existing practice that may

lead to changes when the Interpretation is first applied. This could be a

challenging task in some cases.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will this

Interpretation apply to uncertain treatments of other taxes, for example GST?

Although uncertainty exists

in the determination of GST liability, IFRIC 23 is not applicable since GST is

not a tax on income and not in the scope of IAS 12 (Ind AS 12)/IFRIC 23. Rather

they would be covered under IAS 37 (Ind AS 37) Provisions, Contingent

Liabilities and Contingent Assets. It may be noted that whilst the

underlying principle for recognition in both standards is “probability”, the

measurement basis under the two standards are significantly different.

In a

particular jurisdiction, if tax is not deducted at source with respect to

royalty payments to non-resident the entity is subjected to penalty and also

disallowance of the royalty expenses in computation of taxable income. Is the

penalty and disallowance of the royalty expense covered under IFRIC 23?

Penalty is not a tax on

income and hence are not covered under IFRIC 23. Rather they would be covered

under IAS 37 (Ind AS 37) Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent

Assets. The disallowance of royalty expenses which is included in the

taxable income will be subjected to the requirements of IAS 12 (Ind AS 12) and

IFRIC 23.

Will

Interest and penalties levied by Income tax Authorities be covered under this

Interpretation?

IAS 12 (Ind AS 12) does not

explicitly refer to interest and penalties payable to, or receivable from, a

taxation authority, nor are they explicitly referred to in other IFRS

Standards. A number of respondents to the draft Interpretation suggested in

their comment letter that the Interpretation explicitly include interest and

penalties associated with uncertain tax treatments within its scope. Some said

that entities account for interest and penalties differently depending on

whether they apply IAS 12 (Ind AS 12) or IAS 37 (Ind AS 37) Provisions,

Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets to those amounts.

The IC decided not to add

to the Interpretation requirements relating to interest and penalties

associated with uncertain tax treatments. Rather, the IC noted that if an

entity considers a particular amount payable or receivable for interest and

penalties to be an income tax, then that amount is within the scope of IAS 12

and, when there is uncertainty, also within the scope of this Interpretation.

Conversely, if an entity does not apply IAS 12 to a particular amount payable

or receivable, then this Interpretation does not apply to that amount,

regardless of whether there is uncertainty.

An entity

determines that an uncertain tax treatment is not probable but is possible and

hence disclosure as contingent liability is required. Whether the contingent

liability disclosure will also include the consequential interest and penalty

amount?

Interest amount will be

included in the contingent liability amount if there is no or very little

likelihood of waiver. On the other hand, penalty amount may be waived by the

tax authorities. If it is probable that the penalties may be waived by the tax

authorities, they are not included in the contingent liability amount.

In evaluating

the detection risk, should an entity consider probability of detection by the

Income-tax authorities rather than assuming an examination will occur in all

cases?

The IC decided that an

entity should assume a taxation authority will examine amounts it has a right

to examine and have full knowledge of all related information. In making this

decision, the IC noted that IAS 12 (Ind

AS 12) requires an entity to measure tax assets and liabilities based on tax

laws that have been enacted or substantively enacted.

A few respondents to the

draft Interpretation suggested that an entity consider the probability of

examination, instead of assuming that an examination will occur. These

respondents said such a probability assessment would be particularly important

if there is no time limit on the taxation authority’s right to examine income

tax filings.

The IC decided not to

change the examination assumption, nor create an exception to it for

circumstances in which there is no time limit on the taxation authority’s right

to examine income tax filings. Almost all respondents to the draft

Interpretation supported the examination assumption. The IC also noted that the

assumption of examination by the taxation authority, in isolation, would not

require an entity to reflect the effects of uncertainty. The threshold for

reflecting the effects of uncertainty is whether it is probable that the

taxation authority will accept an uncertain tax treatment. In other words, the

recognition of uncertainty is not determined based on whether a taxation

authority examines a tax treatment.

Will the

principles of “virtual certainty” apply for recognition of current and deferred

tax assets in cases where there is uncertainty of tax treatments?

When the key test of the

Interpretation would result in the entity recognising tax assets (i.e. based on

the probability that the taxation authorities would accept the entity’s tax

treatment), the entity is not required to demonstrate the ‘virtual certainty’

of the tax authority accepting the entity’s tax treatment in order to recognise

such a tax asset. The underlying principle of “probability” will apply for

recognition of current and deferred tax asset arising from uncertain tax

treatments. Consider the example below.

Example 8 – Measurement of tax positions

The management of Entity B

decides to undertake a group-wide restructuring and records a restructuring

liability of INR 1,000,000. Entity B has tax loss carry-forwards of INR

1,200,000. Excluding the restructuring liability, taxable profit for the

current year is INR 2,000,000. Entity B is uncertain whether the local taxation

authorities will accept a deduction for the restructuring costs. However, it

analyses all available evidence and concludes that it is probable that the

taxation authorities will accept the deduction of the INR 1,000,000 in the year

when it is recorded.

Entity B therefore

estimates its taxable profit to be INR 1,000,000 and that this will be fully

offset with tax loss carry-forwards from the INR 1,200,000 available. As a

consequence, there is no current income tax charge in the period and Entity B

determines a remaining tax loss carry-forward balance of INR 200,000. As

management has convincing evidence that Entity B will realise sufficient

taxable profits in the future, it records a deferred tax asset for the unused

tax losses of INR 200,000. Though convincing evidence is required to record a

deferred tax asset on carry forward losses (INR 200,000), the acceptability of

uncertain tax treatments (INR 1,000,000) by the tax authorities is based on the

principle of “probability”.

Conclusion

For many large sized

entities or those with significant income tax litigations or complications,

this Interpretation may well be a significant change. Management and Audit

Committees should ensure that the Interpretation is properly understood and

complied with. Tax advisors too need to get upto speed on the standard, since

this standard may have significant impact on income tax computation and

assessments. _