1. Preface

This is a simple

and short article explaining ‘what is an economic war’. The term: “Trade War”

has become current term. Earlier popular term was “Currency War”. Economic War

is a broader term covering all these smaller wars.

Some common queries

may be: “Why this War?” “What may be the impact of a global economic war on

India/ on global economy?” “Can we protect India from the ill effects of a war

amongst other nations?” “How is it that President Trump imposed sanctions on

Turkey (In August 2018) and Indian Rupee went down?”

This article

presents:

(i) Historical reasons leading to current

Trade War; and

(ii) A few probabilities as results of war. These are considered guesses.

I don’t know actually how future will unfold.

Global events like

Economic Wars are like “elephants”. Writers and observers are like “the

six blind men”. Everyone looks at one or two aspects. Warring parties

involved also create deliberate confusions. I am presenting my views. There are

several other views simultaneously prevalent. Some philosophical thoughts on

Wars are given in notes at the end of the article.

1.2 Definition: An

Economic War is fought mainly for economic benefits using economic instruments

as weapons. Its economic impact can be more devastating than a weapons war. And

yet, there may be no loss of life – at least directly due to war.

1.3 When the war is between a

giant like USA and a smaller country like Venezuela; the smaller nation may get

economically destroyed. When the war is between two giants like USA &

China, both may be damaged. If a full scale Economic World War erupts,

global economy can be seriously damaged. Whole world will be poorer.

Share markets should normally be the first victim. Yet, even now the market

indices have not fallen. This may be because: (i) the cartel of share market

giants may be convinced that all these “War Cries” are just Trump’s typical

style of negotiating. Once the declared opponents concede, there will be no

war. Or (ii) they may be offloading their stocks to the gullible retail

investors. Or (iii) the Cartel may have some other strategy.

1.4 Different economic

weapons are:

i) Currency exchange rate manipulation or

currency dumping (also called Currency War);

(ii) Globalisation & imposition of a particular

currency at the cost of others (Dollarisation);

(iii) Tariffs (Custom duties);

(iv) Import restrictions of the licensing type &

others;

(v) Nationalisation of assets & businesses

belonging to enemy Government and citizens of enemy country. US government has

done this repeatedly.

(vi) Sanctions; rhetoric & threats; etc.

(vii) Finally when

nothing works, weapons wars have been unleashed in the last few decades. The threat

of real weapons war makes rhetoric work. North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un knew

well that his fate will not be different from the fate of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein

and Libya’s Gaddafi. Hence, Kim came to the negotiating table.

1.5 Almost all wars

are fought for economic reasons (Greed of exploiting other nations’

resources for own benefit) and/or for ego issues. Even in today’s modern

world, large nations may go to war largely for ego. Generally many issues are

mixed up as the cause for a war. Mahabharat war was fought largely for

economics & ego. Duryodhan was greedy & egotist. He would not fulfil

his promise. War became necessary. Hitler started 2nd world war for

redeeming the German pride & for economic reasons. USA has started current

trade war with China & several other countries mainly for economic reasons.

1.6 Many people are

greedy. This applies to individuals, societies, corporates and countries.

They want economic benefits at the cost of others. Generally they will start

with exploitations. If the exploited person, group, market does not

understand, fine. If, even after understanding, the exploited group cannot

fight back, there is apparent peace – which in economics may be called “Equilibrium”.

When someone resists, the equilibrium is disturbed. Systems are established

to frustrate resistance. When systems do not work and exploited people/

countries fight back; there may be a weapons war. Generally the exploited lobby

is further destroyed. Rarely the exploited sections win & exploiters lose the

war. Historians

praise victors.

Two illustrations

of economic exploitation within a country are given below: paragraphs 1.7 &

1.9.

1.7 Illustration 1: In

India the “Upper Caste” developed an entire caste system of exploiting the

“Lower Castes”. Religion & mythology have been used to confuse &

confound the poor people; and to establish & continue the exploitative

caste system. Similarly, religion & gender bias have been used by men to

exploit women. They (‘lower’ caste people & women) were deprived of even

education beyond their occupation by birth. It worked for thousands of years.

No amount of social reforms by several reformers including Gandhiji has

effectively removed Casteism from our society. (People living in big cities may

not have the idea of deep rooted caste prejudices in smaller towns &

villages.) Indian Constitution gave equal rights to women; and to every

individual irrespective of caste. Every Indian has a right to education. This

single step has maximum positive impact.

Indian Supreme

Court has now given equal rights to LGBT community & declared

individual freedom as corner stone of our constitution. But even these have

still not completely removed caste based prejudices and exploitations from our

society.

This is an

explosive subject & can provoke heated discussions on several issues.

1.8 My purposes for giving illustrations here are

to show that:

(a) Economic exploitation is all pervasive in

human life. Greed is almost like gravity – pulling every one down. Both

(Greed & Gravity) are not noticed in everyday life. Most people never

realise that they are: (i) exploiting others; and/or (ii) they are being

exploited. We Indians exploit others when we get opportunity. Exploitation is

not special to some people.

(b) At the same time, there can be NO

generalisations. Most social reformers have come from men and ‘upper

castes’.

(c) Exploitations have reversed also. As held by

Honourable SC in India, some backward caste people have abused the provisions

of The Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. In

life there are several cross-currents.

1.9 Illustration 2: In USA, whole population is exploited

by business lobbies. Pharmaceutical Lobby and Insurance

lobby – to name two. For anyone in doubt, ask for costs of medicines and

medical services in USA; and compare with the costs in India. You will realise

how US residents are being exploited by Pharma lobby & Insurance lobby.

Banking Lobby

In the past, US

Government tightly regulated banks & financial institutions which

used public money. They were not allowed to indulge in speculation & in

derivatives with depositors’ money. The banking lobby got the regulations modified

and openly used public savings for dangerous speculation including derivatives.

Banks & Financial Institutions together brought about the Great American

Economic Crisis of the years 2007 & onwards. Economists of the world

know that ‘greed of banks and financial institutions’ was the primary cause for

the crisis. Nothing happened to bankers or to banking laws. Whole focus as

“Cause for Crisis” was shifted to tax planning; and BEPS programme was started

by G20 & OECD.

In USA, the weapons

lobby (Pentagon) is of course most powerful. Whole of USA is being

exploited for continuing wars and weapons productions. In fact, world has

financed American wars. This statement may look unbelievable. I have explained

it in some of my past articles. For a short statement, listen to CNBC interview

of Jack Ma – chairman of Alibaba at:

https://www.cnbc.com/video/2017/01/25/alibaba-chairman-jack-ma-on-meeting-donald-trump.html?__source=sharebar%7Cemail&par=sharebar

Current US initiated Trade War

2. Current

Trade War – started in July, 2018:

2.1 We come to current US

initiated Trade War. The Trade War has already started. So we are not

discussing empty theories. It is also possible that by the time, BCAS Journal

is printed and you read this article; a lot of developments would have taken

place.

2.2 To understand the

reason why Trump has started this trade war, we may consider several matters.

2.3 Trump’s theories: Trump claims that USA is the most liberal

country and rest of the world is taking undue advantage of USA. This is at the

cost of GDP, trade deficits and employment in USA. Since other countries are

not responding to his appeals; war is necessary. He also claims that USA is the

most powerful economy as well as army. So the war will be won by USA.

2.4 Trump has conveniently forgotten

past strategies implemented by USA. Today, when those strategies have

resulted in unemployment in USA, Trump loves to blame China & others. (See

Jack Ma’s interview on link given under paragraph 1.9 above and also see

paragraphs 5 & 6 below.)

2.5 War mongering: Every warrior – whether Individual or

Government – spreads several theories including incorrect theories that justify

the war. World has neither forgotten nor forgiven the campaign that US & UK

had spread when they decided to attack Iraq. They alleged after September 2001

(World Trade Centre attack by Al Qaeda) that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had

accumulated “Weapons Of Mass Destruction” (WMD) which could be used

against..(?). It was known that Iraq neither had WMD nor the capability to

strike USA. It was later that the world realised that real purpose of attack

was – to punish Saddam Hussein – who defied US order to ‘sell oil only in US$’.

Saddam sold oil in Euro and got killed. Iraq got economically destroyed for not

obeying USA.

This is a clear

illustration of the hypothesis (Please see paragraph 1.6 above.) that: “when

economic exploitation is resisted, the victim is destroyed by weapons war”.

For eg., Saddam Hussein resisted US

Dollarisation of Iraqi crude oil exports. And Iraq was attacked by US. And

the world remained a silent spectator.

2.6 Even a strong army

may not open war on all fronts. But initially it seemed that Trump

opened up war on several fronts. He blamed almost all – (i) known adversaries

of USA as well as (ii) countries that considered themselves as strong allies of

USA. (Please see Note 1 below.) This second category includes Mexico, Canada,

UK & European Union (EU). After a lot of war rhetoric against EU; on 24th

July, 2018, EU president Jean Claude Juncker met Trump and a temporary truce

has been signed. (Please see note No. 5 below.)

India has been

warned by Trump. But India is an insignificant trade partner of USA and hence

is on the low burner. (Don’t feel bad. We, Indians are still insignificant in

world economy.) There is also another equation of – using India to fight China.

So how USA behaves with India – is yet to be seen.

2.7 Some History: After 2nd

world war, USA turned benevolent to all war victim countries including the

countries attacked by USA – Germany and Japan. To protect Western Lobby from

Russian threat, NATO was formed. Under NATO and similar other

agreements, the US army is present in every West European country and many

others. 72 years after the end of World War II, and 26 years after

dismemberment of USSR, US army is still present in Europe and several other

countries. Hence even Germany observes restrain while protesting against US

policies. Others have to simply toe the line.

2.8 Truth under the surface:

In USA, the President is most conspicuous person. He is the spokesman

for the whole Government. But his real power and impact may be far less than

apparent. There is an Establishment of think tanks, bureaucrats & lobbies

that works. They continue to work irrespective of the President for the time

being.

Illustration: When, in 1981, Ronald Reagan became the President, many

observers wrote him off as an ineffective failure from film industry. In 1982,

preparations for an Economic War against USSR started. (For some

details, see Note 2 below.) Reagan retired in 1988. The Economic attack on USSR

was made in the year 1992. Credit for the great event – destruction of USSR –

is being given to Reagan. However, who actually fought the war? The Establishment

which remains behind curtains fought the real economic war.

US policies (Paragraphs 3 to 6 below):

3. Super

Power No.1

3.1 It is US policy that US

should always remain Super Power No.1. All other countries should start from

No. 11 & onwards. If any country becomes so strong that it can challenge;

or does challenge US authority in some serious manner; it will be destroyed by

several alternatives available with USA. One of the alternatives is: Economic

War. Economic wars may take ten years preparations also.

3.2 I believe that an

action plan to hit China’s powers was already prepared long before Trump

decided to stand in election. Now that the Establishment has got a suitable

President, the war is started.

3.3 China has started

serious process to make Chinese Yuan a currency of international

trade. It has asked Russia, India and several countries to start their

bilateral trade in bilateral currencies. This is a challenge to the

Dollarisation of global trade.

China has started

serious endeavour to reduce its holding of US treasury bonds. China is

developing international foreign exchange markets in Yuan. This is a direct

challenge to Dollarisation of the international trade & investment.

China is today 2nd

largest economy. Chinese military and mind-set are the only powers on

earth that can say “No” to USA. (Apart from President Putin of

Russia.) The “One Belt One Road”

project by China is an audacious plan to increase Chinese influence globally.

Expanding Chinese bases in South China Sea; building a chain of ports in

countries like Srilanka, Pakistan, Djibouti etc., is a threat to American ego

for its largest military presence all over the world.

These are more than

enough causes for USA to set in motion a plan to destroy China. The plan may or

may not be similar to the plan for USSR. The Establishment waited for

suitable opportunity and struck when suitable president was in chair. Further

plans will unfold as the days go by.

4. Dollarisation of Global Trade:

It is another

unwritten order that whole world should do its international trade in US $.

When this order is not obeyed, see what happens:

4.1 Iran & Venezuela are facing allegations of being

terrorist nations. Severe sanctions are imposed on them crippling common life.

Their offense: exporting crude oil in currencies other than US$.

4.2 South East Asian

countries – Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, Philippines – went

insolvent in the year 1997 because they started exporting their goods to Japan

in Japanese Yen instead of US $. President Suharto of Indonesia committed

another offense of disobeying US order of allowing independence to East Timor.

(Population 12,00,000.) Suharto lost his power and Indonesia lost East Timor.

4.3 Iraq was attacked

and destroyed because it was selling oil in Euro. European Union understands

fully well that this is an indirect attack on EURO. However, EU can’t do much

except being a silent spectator.

4.4 EU launched Euro on 1st

January, 1999. This was a challenge to Dollar

monopoly of international currency. Hence EURO suffered a massive

economic attack. Its exchange rate dropped from “1 Euro = $ 1.2” to “1 Euro = $

0.8”.

These are just some

illustrations of how US enforces Dollarisation of global trade &

investments – by fighting economic wars on the world.

4.5 Having Dollarised

global financial settlements, now US has Weaponised Dollar. She is using

$ as a weapon. If any nation, any bank or financial institution disobeys US

dictates, its international payments will be crippled. That entity’s international business will

almost be stopped.

5. Using World for

outsourcing labour:

Outsourcing is done

for many decades. Computer software outsourcing through the internet made it

famous. However, outsourcing manufacturing functions is far older tradition.

5.1 There was a time

when the US Establishment adopted a policy. “Reserve US manufacturing for high

tech products and for weapons. Even for high tech items US MNCs need to own

only the technology. Manufacturing was shifted abroad and commoditised. All low

value manufacturing should be outsourced.” First outsourcing started with Japan.

Then major supplier of labour was China. The Establishment’s theory was

as under. Manufacturing within USA has high labour cost. China can provide

cheap labour. So let China manufacture goods. US want only sales and

distribution of cheap goods from abroad. This way, US consumers would get goods

at cheaper prices. And MNCs will make higher profits. Around 1980, China was

‘advised’ to devalue its currency. Chinese currency was devalued from Two

Yuan per $ to Four Yuan per $. By the year 1993, Yuan depreciated to Eight

Yuan per Dollar.

5.2 A devaluation of Chinese

currency means: (i) US gets same goods for much less dollars. (ii) Chinese

individual exporter –who counts his profits in Yuan, feels that he is still

making good profits. (iii) China as a whole suffers massive losses. In fact

devaluation meant poor Chinese people subsidising rich Americans.

American MNCs would

go to China and set up factories there. China would feel happy as “foreign

direct investment” was flowing into the country bringing precious dollars.

However, all low value products and environmentally harmful production was

being shifted to China.

5.3 This was an

elaborate plan. Explaining it in easier terms would mean several pages of

article. I would end this second US strategy in short here.

6. Results of outsourcing were:

6.1 Americans were getting goods

at low prices. Inflation within USA was always under control.

American consumer was happy. American business made good profits in marketing

and distribution.

6.2 American labour

jobs were exported abroad. This was planned by US establishment. It was not

an unknown development. In a super capitalist country, it is a declared policy

that “there is no job security in USA.” Business creates several entry barriers

for competition and secures its safety. But as far as labour is concerned, it

has to simply hope. Simultaneously, even education is fully commercialised in USA.

It is very costly. Middle class and poor cannot afford higher education. Hence

supply of blue collar labour kept on increasing and employment opportunities

kept on going down.

6.3 This outsourcing

policy has gone on for a few decades. Whole generations of middle class have

become poorer than their parents. Trump realised this gap in US economic

system. He used it for his political advantage. Now, to fulfil his election

promise to bring jobs back to USA, he has to start a Trade War. This is what

the Establishment wants.

This is the

reason why USA has started a Trade War.

See preface

paragraph 1(i).

Summary so far: There is a serious challenge to USA’s Super Power status and

monopoly of Dollar. USA has started a pre-emptive strike before the challenge becomes

serious.

Note: US economic policies require decades of study to understand. It is

difficult to explain in one article. I have tried to simplify and summarise.

Another way of understanding real life economics is personal discussions at

BCAS study circle for International Economics.

7. Indian Government:

Very few Indians

give due importance to Economics Wars. Fewer still understand it. In these

chaotic and dangerous times we need a Government that fully understands the

risks to which whole world is now exposed; and implements plans to protect

Indian economy. In my humble submission our present Prime Minister understands

these matters far better than most other PMs. He has the will power and the

capability to protect Indian economy.

We may remember

that in 1992 & 1997 a cartel did attack primarily USSR and South East Asia.

Attacks on Indian economy were incidental. The 2007 American Economic Crisis

spread over almost entire globe. In all three instances, it was primarily GOI

and RBI which managed and protected Indian economy. Government bureaucracy

continues to be same – probably, now more competent and empowered. We should be

able to sail through.

Sadly, we do not

have any private sector think tanks that can help GOI.

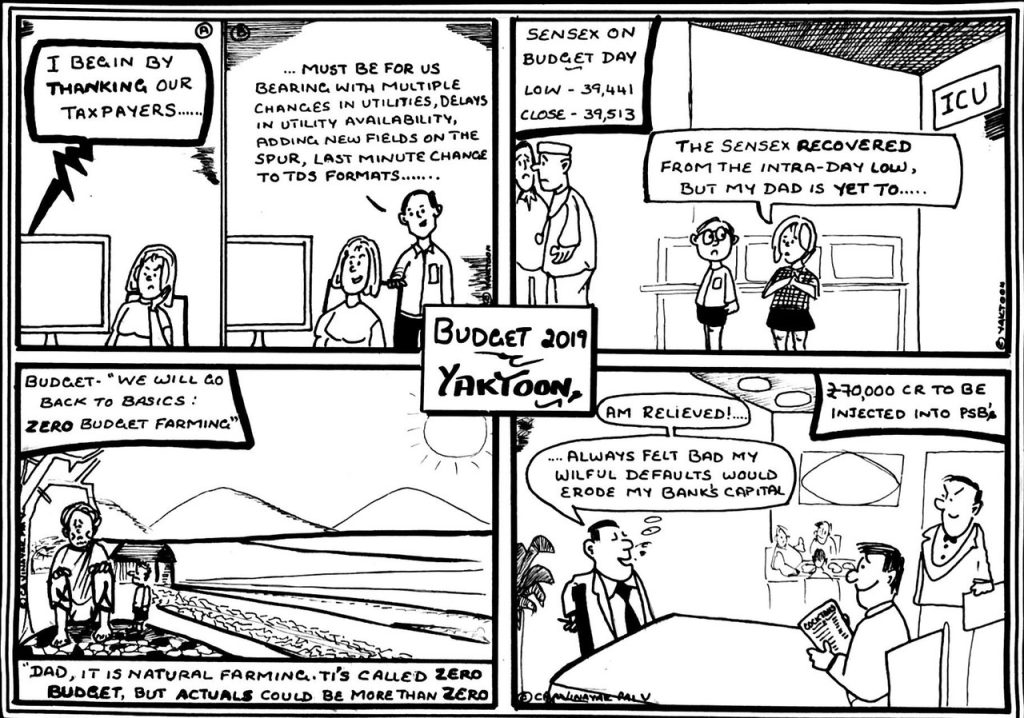

8. Indian share market:

For a long period

Indian share market has behaved as if it has no connection with Indian economy.

In a war, such myths get exposed and destroyed. If the war is prolonged, Indian

share market can be badly affected.

9. Can we estimate how the Trade War will proceed

further?

What will be the

results for Global economy?

See preface

paragraph 1(ii).

The war can go any

which way. It is difficult to guess how it will go. And yet, there are people

with huge investments in global markets. Apart from investors in shares and

securities, there are large industrial investments that can be seriously

affected. They would want considered estimates of the consequences of the

current Trade War. Can anyone advise them? I cannot advise. But I am presenting

some extreme opposite probabilities.

Some probable

results:

9.1 Trump made all

kinds of noises, insults and threats against several countries. But he settled

without firing a single bullet – with North Korea and Mexico. There is a

compromise of sorts with EU. Canada may soon fall. It is possible that Trump

may win the “War on the World” simply by threats. Only China refuses to

succumb.

9.2 Past Economic Wars – Instruments used:

Some of the past

Economic Wars have shown that these wars are fought by US Government using

following instruments:

(i) media for

public mind manipulation; (ii) IMF, UN & World Bank; (iii) cartel of banks

& financial institutions (iv) American Think Tanks (v) fact that Dollar is

the global currency.

We may refer to all

these together as Economic War Group. Note that only USA has all these

war instruments.

Secrecy of their strategy is their strength. They will never tell “what” is

their target; and “how” and “when” they will try to achieve the target.

The issue of “When”

is answered as the Trade War with China has already started.

Let us assume that

Chinese Government is fully aware of this strategy of economic wars. To fight

this strategy, China needs similar group of international institutions under

its control; control over global media; global currency; and so on. It is well

known that no country other than USA has this strength. So, how can China win

the war? Make your own guess.

9.3 China’s possible alternative response:

In absence of a

comparable Economic War Group, what can China do? What can be the consequences?

Consider the war

background before proceeding.

1. USA is the largest debtor country.

Borrowing is now a compulsion. She needs to borrow every day $ 2 Bn. If the

world stops subscribing to US treasury bonds; US Government will stop

functioning.

2. Several countries around the world are fed

up of US hegemony. But “Who will bell the cat?” Who will throw the first

salvo? Once a nation strikes against US Economic war; many nations may join.

3. Trump is unpopular within and outside

USA. Long hand of law may catch up with Trump. Whether the next president will

be friendly with the “Establishment” or not; is an issue.

Possible

Response: Let us say, China takes following steps

& US responds step by step or at one stroke. (Note: This is pure

hypothesis. And yet, it is possible.) China owns largest quantity of US

treasury bonds and currency as its foreign exchange reserve.

CHINA

China dumps US

treasury bonds & currency worth one trillion Dollars in the market in

one day for cash settlement. Then China refuses to buy any further US treasury

bonds. China refuses to sell any goods to USA on credit or for $ payment. She

demands either gold or Yuan or commodities in payment for any export to USA.

USA

US Treasury bond

market can crash.

Or

US Government &

Economic War Group can try to buy entire stock on the same day. This may not be

practical because China would demand cash payment. This would not be a

“futures” transaction. This would be sale by China “in Cash” for immediate

payment.

EU, Canada &

Mexico may follow China and refuse to sell goods on credit to US customers.

US need to borrow

every day. If the funds are not available, Government machinery will stop. It

has now happened several times that US Govt. could not pay its expenses &

non-essential services had to be stopped. Then the Govt. increased borrowing

limits & paid its expenses out of borrowings. Fiscal Cliff has been

discussed several times. It is a serious reality for which no American

Government has any solution. Real financial position of USA is weaker than what

is made out.

Now, if the world

stops lending to USA, what can US do? She will have to finance expenses by

simply printing notes. If there is no outside taker of US notes, deficit

financing will cause immediate and significant inflation. A country that

has not seen more than 2% inflation, will be shocked by 10% inflation.

More important, a

lot of commodities that US public takes for granted, will simply not

be available. US talks of shifting production from China to USA. Can it

start fresh factories in a short time? There can be huge uproar within USA

making US Government fall. So far, all wars have been fought beyond American

land. This war will be fought within USA. For the first time Americans

may suffer consequences of the war.

China’s response to

Economic War – by an attack on US $ – may work better if Japan, EU, Canada

& Mexico etc., join in the Economic World War. Normally US would succeed in

“divide & rule policy” & won’t allow all of them to join

together. However, the way Trump behaves, probability of a combined front

against USA has improved. Against a combined front USA is doomed. In absence of

a combined front, ‘who will win’ becomes uncertain. Only certainty will be –

world economy will be damaged.

9.4 How long the world will go

on fighting?

How can world

avoid all wars?

One solution

appears. If there were a World Government, all wars would be

unnecessary. We have a good experience also. In India, at some time, there were

more than seven hundred kingdoms. Huge amount of their resources were spent on

war & defence. Now India is one country. All Kingdoms have merged into one.

There is no war within India. Of course, there are differences and troubles.

But these can’t be compared with wars.

Another solution

may be: At the root of all wars, there are greed and ego. Consider –

hypothetically, a solution where greed and ego are replaced by love &

spirituality. There would simply be no wars of any kind. Not a single soul

would go without food, medical services, education & home. Then the form of

Government would be irrelevant.

May God Bless human

kind.

Notes:

Note 1. Allies: (See para No. 2.4) India, Pakistan, Britain or

any other country may consider itself to be a friend of USA. However, in

economics as in politics; no one is a permanent enemy and no one is a permanent

friend. Britain and European Union (EU) realised this fact when US cartel

attacked Euro on 1st January, 1999 – the day of Euro’s launch.

Trump’s accusations against EU have made this fact abundantly clear.

Note 2. Outsourcing & Exchange Rates:

Japan:

In the year 1940,

Japanese Yen to US $ rate was 4 yen = $1. After 2nd

world war defeat of Japan huge inflation took place in Japan. US occupied Japan

& controlled its economy. It is then that US outsourcing to Japan started.

Yen was depreciated to 360 Yen = $1.

After a few

decades, Japan grew in manufacturing strength. Japanese cars started winning

the competition with American cars. This is when Japan was asked to revalue its

currency. Eventually, it appreciated to 140 yen to a dollar in the year 1990.

And Japan went into deep recession. 1990s was called the lost decade for Japan.

By now rate has gone up to 112 yens per dollar.

US Strategy is: when a country is pure commodity supplier, its currency must be

down. When it starts competing with US manufacturers, its currency must

appreciate.

My observations: Japan is excellent in manufacturing and poor in international

economics. It followed the dictates of US Establishment in exchange rate policy

and suffers. China is refusing to obey the orders by the Establishment. Hence

the Trade War.

Note 3. An Illustration of past

Economic War: 1992 economic war on USSR.

In the year 1982

under president Reagan, US Establishment started preparations for economic war

against USSR. For the public & media consumption, “Star Wars” were started

to maintain US superiority in air war over USSR. Real strategy was – massive

expenditure in developing missiles and counter missiles made USSR insolvent, US

printed dollars & world grabbed dollars as $ was global currency. World

was financing US Star War. No one was buying USSR Rouble & hence no one

financed USSR in her Star War. Result was – USSR insolvency.

Reagan retired in

1989. In the year 1992 USSR was economically destabilised because of sudden

change from communist regime to democratic regime installed by President

Mikhail Gorbachev. KGB arrested Gorbachev and nation was thrown in chaos. At

that time the G4 – US, UK, France and Germany together with their cartel of

banks and financial institutions struck. USSR got divided into fifteen

countries and economically went insolvent. It got reduced from the position

of Super Power No. 2 to 11. USA won the Cold War without losing men or money.

Note 4. Strategies like outsourcing

may not be a Government of USA decision. Nor a one man decision. Initially,

businesses found it profitable to shift labour abroad. Then Government

supported it. Eventually it developed into a full national strategy.

Note 5. Trump’s negotiating

strategy is now famous. “First threaten the opponent with dire

consequences. When the opponent is mentally broken, negotiate on your own

terms.” This is what he did with North Korea and Mexico. This is how he

negotiated a temporary truce with European Union.

This truce has

given USA tremendous benefit. Consider the news that China was making overtures

with EU to make a joint attack on USA. EU was scared but was considering

joining hands with China. Now Trump has ensured that EU will stay with US.

China is the lonely warrior.

Note 6. More and more

nations are disillusioned about US hegemony. Finance Minister of Germany

– Mr. Heiko Maas came out with clear statement that – US is

using $ monopoly for suppressing other nations. Even the global Swift Payment

system based in Belgium is using US$ for settlements. EU must come out with its

own international settlement system independent of US $. Prime Minister Ms.

Merkel of Germany quickly contradicted. She said: US defence deal with Germany

is far more important. See the link –

https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-quashes-german-foreign-minister-heiko-maas-anti-american-dream/.

Soon French

President stated that US defence deal is no longer reliable. EU must not depend

exclusively on US for its defence.

Note 7. Ego: It is said: “Eleven Sadhus can stay in one

hut. But two Samrats cannot stay in one Samrajya”.

Note 8. Advait:

1. Indian philosophy of Advait has taught me

that “We are all one”. “?? ?? ?? ??” is a famous Indian slogan.

2. Hence no one is my enemy. When “We are all

one”; the concept of enemy is void ab initio.

3. We have to live in this practical Sansar

knowing the philosophy and yet being alert about people who, under the

influence of greed, are out to harm us. Protect ourselves. Protect the weak.

Hate none.

Note 9. Geeta:

Consider what Trump

representing US Government thinks: “I am the Super Power No. 1. I must get what

I demand. I can & will destroy all competition. Who can fight me?”

See here Geeta

chapter 16 shlok 14 as translated by Swami Chinmayanandji: (Without any

modification.)

“Businessmen in

the world, unknown to themselves, constantly chant this stanza in their heart

of hearts. “I destroyed one competitor in the market, and now I must destroy

the remaining competitors also.” …”In fact, what can those poor men do to stop

me from doing what I want?”… “Because there is none equal to me in any

respect…I am the Lord. I enjoy, I am the most successful man. I am strong in

influence, among political leaders, in my business connections, and in my bank

balance. I am strong and healthy….” This, in short, is the ego’s SONG OF

SUCCESS that is even hummed in the heart of a true materialist. Under the spell

of this Satanic lullaby, the higher instincts and the divine urges in man go

into a sleep of intoxication.

Most people keep

Geeta on one side while analysing commercial/ economic/ war matters. I

personally submit: Geeta is a way of life. Without incorporating principles of

Geeta in life, it (life) has no meaning at all. Consequences of a person’s

actions will be as projected in Geeta.

Nature has its own

way of dealing with any person (Individual, company or Government) who

continuously abuses others. Nature’s ways are unpredictable and beyond our

logic.

10. In my reading,

it is possible that the Trade wars started by USA – together will several other

factors; will bring about the downfall of USA. Then what? Some other greedy

people will exploit the world. Men have been fighting wars for thousands of

years. When will it stop?

Wars will stop when

people become free from forces of Maya – Greed and Ego. In other words, wars

will stop when people become spiritual.