1 Introduction

1.1. In 1920-1923,

the International Chamber of Commerce (‘ICC’) commenced a process to

develop a model income tax treaty in the immediate aftermath of World

War I. It was the period of conception for the model treaties of today.

Though the work has been lost as the world has evolved, it is

instructive with respect to the current tax policies being espoused by

Source Countries.

1.2. T he repercussions of the World War I

left England with enormous war debt. There was a material flow of

commerce between England and India. For the most part, England

transferred capital, technology, and access to global markets to

affiliates in India. India responded with commodities and produced

goods. England became a creditor and India a debtor. These dealings led

to a major concern as to how income from these activities should be

shared between “Resident” and “Source” countries.

1.3.

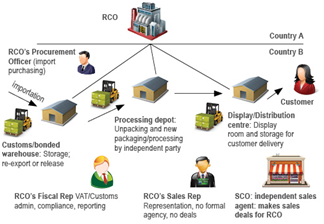

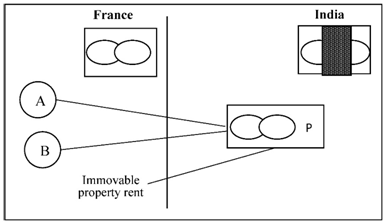

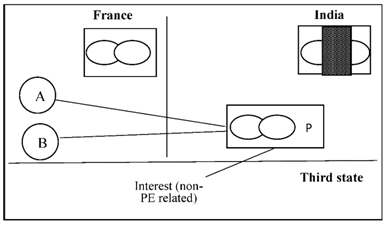

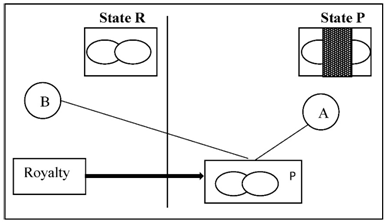

D iagram ‘A’ is still prevalent in present day scenario where tax

havens like BVI, Cayman, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Bermuda, Costa Rica,

etc. are used as a means to drain all the profits generated in developed

and developing countries. 1.4. I CC in its interim report in 1923

proposed what we would call today a profit split or formulary allocation

methodology, to address income allocation between Residence (Creditor)

and Source (Debtor) countries. The proposal was similar to the combined

income methodologies typically used today, to resolve major Competent

Authority cases under treaty mutual agreement procedures cases between

countries with Multinational Enterprise (MNE) in the middle. Frankly, it

is also similar to the methodologies for evaluating intangibles in the

2012 OECD discussion draft. 1.5. T he OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines

(OECD Guidelines) as amended and updated, were first published in 1995;

this followed previous OECD reports on transfer pricing in 1979 and

1984. The OECD Guidelines represent a consensus among OECD Members,

mostly developed countries, and have largely been followed in domestic

transfer pricing regulations of these countries. Another transfer

pricing framework of note which has evolved over time is represented by

the USA Transfer Pricing Regulations (26 USC 482). The European

Commission has also developed proposals on income allocation to members

of MNEs active in the European Union (EU). Some of the approaches

considered have included the possibility of a “common consolidated

corporate tax base (CCTB)” and “home state taxation.” 1.6. The United

Nations for its part published an important report on “International

Income Taxation and Developing Countries” in 1988. The report discusses

significant opportunities for transfer pricing manipulation by MNEs to

the detriment of developing country tax bases. It recommends a range of

mechanisms specially tailored to deal with the particular intra-group

transactions by developing countries. The United Nations Conference on

Trade and Development (UNCTAD ) also issued a major report on Transfer

Pricing in 1999.

1.7. T he Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (“OECD”) has had an absolute presence as a

provider of global guidelines for international taxation area. While the

OECD is based on the consensus of 34 developed countries, it has

played an enormous role on the international taxation issues such as

setting guidelines for model tax treaty, transfer pricing and permanent

establishment, and tackling the international tax avoidance issue.

1.8.

O n the other hand, the role of the United Nations (UN) having a

membership of 193 economies (whose working is not consensus based), on

the taxation issue had been limited such as making the model tax treaty

for developing countries. However, the UN has recently increased the

presence on this area especially in the field of transfer pricing and

has released its Manual on Transfer Pricing in May, 2013.

2. Evolution of Transfer Pricing in India

2.1.

T he year 1991 is considered a watershed year in modern India’s

economic history. It was after all the year in which the Indian economy

was “opened up,” i.e., liberalised by the then widely hailed Finance

Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, the former Indian Prime Minister. The

economic reforms of 1991 were far-reaching including opening up India

for international trade and investment, taxation reforms, inflation

controls, deregulation and privatisation. These reforms opened the

floodgates and caused over the next two decades huge amounts of foreign

cash flows into and out of India.

2.2. From a taxation

perspective, these huge foreign cash flows brought into bright spotlight

the issue of transfer pricing wherein the Indian companies ought to

price their services, or imports as the case maybe, to their group

companies outside India at arm’s length, i.e., what they would charge,

or pay for in case of imports, to an unrelated third party in the open

market.

2.3. The underlying logic is that Indian companies might

under-charge their services or over-price their imports to group

companies and thereby shift their profits abroad for various reasons

such as for saving taxes if the tax rate abroad is lower, etc. The

Indian Government, like most others, is heavily dependent on tax revenue

and simply cannot ignore tax avoidance issues on this scale. So it

stepped up in 2001 and amended the Indian Income-tax Act of 1961 (‘ITA

’) via the Finance Act of 2001 and added a new chapter titled “Chapter

X: Special Provisions Relating to Avoidance of Tax” and introduced

section 92 in Chapter X containing s/s. 92A to 92F and Income Tax Rules

(Rule 10A-10E) laying out specific TP provisions for the first time. In other words, the foundations of the Indian TP maze were laid!

2.4.

In India, under the ITA , prior to the introduction of TPR in 2001,

section 92 was the only section dealing with the Transfer Pricing and

that was the only statutory provision available to the Revenue

Authorities for making certain adjustments in the income of a resident

arising from the business carried on with a non-resident as provided in

the said section 92. Rules 10 and 11 in the Income-tax Rules,1962 (‘the

IT Rules’) were also available for this purpose, i.e., Old Provisions.

However, these statutory provisions and the Rules were not giving

sufficient powers to the Revenue Authority to find out whether the

foreign companies/non-residents operating in India or earning in India

were being taxed on their Indian income on an arm’s length basis and at

the same time, necessary powers were also lacking in most cases, for

making appropriate adjustments in the Indian income of such entities in

cases where the transaction appeared to be not on an arm’s length basis.

At the same time, under the ITA , another provision contained in

section 40A(2) which deals with the disallowance of expenses to the

extent they are found unreasonable where the payments are made to

related parties was also limited in scope to deal with the cases of

cross border transactions. With the liberalisation of policies with

regard to participation of the MNE in the Indian economy, need for

comprehensive provisions to protect the interest of the Indian Revenue

and collect the legitimate due share of taxes in cross border

transactions as also a need to streamline the Law and procedure in that

respect was felt. That is how, new provisions relating to Transfer

Pricing have been introduced by the Finance Act, 2001 (in place of the

above referred section 92) w.e.f. Asst. Yr. 2002-03 i.e., New Provisions.

Objects of the New Provisions

2.5. As stated in the earlier para, the new provisions have been introduced in the act to overcome the limi- tation of the old provisions and also to make more comprehensive provisions in the act and the rules relating to transfer pricing to safeguard the interest of indian revenue with regard to income arising in cross border transactions. the new provisions (sec- tions 92 to 92f) are contained in Chapter-X of the it act with the heading “special provisions relating to avoidance of tax” and therefore, the introduction of the new provisions is primarily an anti tax avoidance measure. This is also further fortified by the fact that CBdt Circular no.14 of 2001, while explaining these new provisions, also explains the same under the head “new legislation” to curb tax avoidance by abuse of “transfer pricing.” the object of these pro- visions gets clarified from the following two paras of the said Circular:

“55.1. The increasing participation of multinational groups in economic activities in the country has given rise to new and complex issues emerging from transactions entered into between two or more enterprises belonging to the same multi- national group. The profits derived by such enterprises carrying on business in India can be controlled by the multi-national group by manipulating the prices charged and paid in such intra-group, transactions, thereby, leading to erosion of tax revenues.

55.2. Under the existing section 92 of the IT Act, which was the only section dealing specifically with cross border transactions, an adjustment could be made to the profits of a resident arising from a business carried on between the resident and a non-resident, if it appeared to the Assessing Officer that owing to the close connection between them, the course of business was so arranged so as to produce less than expected profits to the resident. Rule 11 prescribed under the section provided a method of estimation of reasonable profits in such cases. However, this provision was of a general nature and limited in scope. It did not allow adjustment of income in the case of nonesidents. It referred to a “close connection” which was undefined and vague. It provided for adjustment of profits rather than adjustment of prices, and the rule prescribed for estimating profits was not scientific. It also did not apply to individual transactions such as payment of royalty, etc., which are not part of regular business carried on between a resident and a non-resident. There were also no detailed rules prescribing the documentation required to be maintained.”

2.6. The above object would be very relevant for the purpose of interpreting the new provisions because the provisions deal with the computation of income from an “international transaction” between “associated enterprises” (‘AES’) and provide the basis of such computation.

3. Transfer Pricing regime in India

3.1. Under the new provisions, any income arising from an “international transaction” is required to be computed having regard to the arm’s length price (alp). The ALP is defined to mean a price which is applied (or proposed to be applied) in a transaction between the persons other than aes, in uncontrolled conditions. It is also clarified that the allowance for any expense or interest arising from an “international transaction” shall also be determined having regard to the alp. in short, the law now expects that computation of income in such cases (including allowance for expense) should be based on a price which one would consider for the purpose of entering in to a transaction with an unrelated party (i.e., not “associated Enterprise” as defined). – [Section 92(1) and explanation thereto and section 92f(ii)].

3.2. It is also provided that in an “international transaction” or “Specified Domestic Transaction” (“SDT”), if under mutual agreement or arrangement between aes any arrangement for sharing cost, expenses etc. incurred (or to be incurred) in connection with a benefit, service or facility for the benefit of such aes is made, the same will also be covered within the new provisions (hereinafter such arrangement is referred to as Cost sharing arrangement) and accordingly, such Cost sharing arrangement between the aes should also be determined having regard to ALP of such benefit, service or facility, as the case may be. accordingly, the allocation or apportionment of cost or expense under such arrangement amongst various aes is also required to be made having regard to the ALP of such benefit, service or facility, as the case may be. – [Section 92(2)]

3.3. s/s. (2a) of section 92 provides that in relation to the SDST would be computed having regard to ALP:

1) Any allowance for an expenditure, 2) any allowance for interest, 3) allocation of any cost or expense and 4) any income. The first two clauses would be relevant from viewpoint of an assessee who incurs the expenses or interest in relation to sdt. the third clause would be relevant in case of cost sharing arrangements, whereby the cost or expense needs to be allocated between two or more assessees having regard to alp. The fourth clause would be relevant from the angle of determining the income of an assessee undertaking an sdt.

3.4. A specific provision has also been made stating that the above referred provisions providing for determining income or Cost sharing arrangement in an “international transaction” on the basis of alp shall not apply if the application of those provisions has the effect of reducing the taxable income or increasing the loss under the act which may otherwise be comput- ed on the basis of entries made in the relevant books of account. Therefore, in effect, the above provisions will have to be applied only if the application thereof results into tax advantage to the Revenue. – [Section 92(3)]

3.5. Considering the definition of the term “International transaction” and “associated enterprises,” the pro- visions of section 92 will be attracted only in cases where any income arises (including allowance of ex- penses), or in cases of Cost sharing arrangement, only if the transaction is between two AEs [except in exceptional cases, referred to section 92B(2)], and at least one of the parties to the transactions is non-resident and the transaction is regarded as “international Transaction” as defined in the Chapter. Consider- ing the very wide definition of the terms “Associated enterprises” and the “international transaction,” the scope of the applicability of the provisions of section 92 is very wide and therefore, one has to be very careful before coming to conclusion as to non-applicability thereof, particularly in cases where the transaction involves a related non-resident.

? Associated enterprise (AE)

3.6. the provisions relating to computation of income or Cost sharing arrangements will be attracted only if the transaction is between “associated enterprises” and therefore, the understanding of the term “associ- ated enterprise” (ae) is very crucial. this has been exhaustively defined in section 92A.

3.7. The tests to be applied for determining whether an enterprise is an AE or not [as contained in section 92a] can be divided into two parts viz. General tests and Specific Tests.

3.8. Under the General tests, in substance, it is provided that if one enterprise, directly or indirectly (or through one or more intermediaries), participates in the management, control or capital of the other enterprise or if common persons similarly participate in the management, control or capital of both the enterprises, then, such enterprise could be regarded as “associated enterprise” (ae). these General tests do not lay down any specific method or percentage to determine as to when the same should be applied. therefore, the application of General tests for such purposes will depend on the facts of each case. this will have to be understood in the context of these provisions. Broadly, these provisions are similar to the provisions contained in article 9 of the Model Conventions (OECD as well as UN). – [Sec- tion 92a(1)]

3.9. Under the Specific Tests, it is provided that two enterprises shall be deemed to be aes if, at any time during the year any of the Specific Tests is satisfied. for this purpose, twelve different tests have been provided and the power has also been given to pre- scribe further tests based on a relationship of mutual interest between the two enterprises. however, till date no such additional test has been prescribed. a debate is on as to whether the Specific Tests are the examples of the General tests or each one of the Specific Tests is exhaustive in the sense that once the same is satisfied, the enterprise should be regarded as ae irrespective of the fact as to whether the test of participation in management, control or capital (referred to in the General Tests) is satisfied or not. – [Section 92A(2)]

3.10. With regard to independent application of the General tests, an important question is whether provi- sions contained in section 92a(1) are in any way controlled by the provisions of section 92a(2). in this context, the issue was under debate as to where the two enterprises do not become aes under any of the Specific Tests, then, whether by applying the General tests independently, two enterprises can be brought within the meaning of aes u/s. 92a(1). it seems that this issue gets resolved on account of the amendment made in section 92a(2) by the finance act, 2002 read with the memorandum explaining the relevant provisions of the finance Bill, 2002, which reads as under:

“The existing provisions contained in section 92a of the income-tax act provide as to when two enterprises shall be deemed to be associated enterprises.

It is proposed to amend s/s. (2) of the said section to clarify that the mere fact of participation by one enterprise in the management or control or capital of the other enterprise, or the participation of one or more persons in the management or control or capital of both the enterprises shall not make them associated enterprises, unless the criteria specified in s/s. (2) are fulfilled.”

3.11. In cases where two enterprises have become aes by applying the provisions of section 92a of the act, an interesting issue is under debate as to whether, by taking recourse to article of the relevant treaty dealing with AE [similar to Article 9 of the OECD/ un model treaties], it is possible to argue that such enterprises are not be regarded as aes if, by ap- plication of the provisions of article 9 of the relevant treaty, they do not become aes.

3.12. For the purpose of this Chapter, the term “enter- prise” has already been exhaustively defined and the definition of the term is very wide. In effect, the term “enterprise” would include every person carrying on any activity (which may or may not amount to business) relating to the production, storage, supply, distribution, acquisition or control of articles or goods or know how, patent etc. in fact, list of the activities is so wide that, by and large, every activity may get covered. even a “permanent establishment” (pe) carrying on such activity is also treated as an “enterprise” for the purpose of this Chapter. Therefore, even a Branch of a foreign Bank carrying on any activity in india will be regarded as “enterprise.”

3.13. The term PE, for this purpose, is defined to include a fixed place of business through which the business of the “enterprise” is wholly or partly carried on. therefore, it appears that the `pe’ would be regarded as an “enterprise” only when it carries on business and that too through a fixed place of business. – [Section 92F(iii) and (iiia)].

? International Transaction

3.14. for the purpose of applicability of section 92 a transaction giving rise to income or a transaction relating to Cost sharing arrangement has to be an “international transaction.”

3.15. The term “international transaction” has been ex- haustively defined to mean transaction between two or more aes (of which at least one of them should be non resident) in the nature of purchase, sale or lease of any tangible or intangible property or provision of services or lending or borrowing of money, or any other transaction having a bearing on the profits, income, losses or assets of such en- terprise etc. and includes a Cost sharing arrange- ment between two or more aes. Considering the wide meaning of the term “international transac- tion,” by and large, every transaction between two aes involving at least one non resident will get covered. it is not necessary that for a transaction to be an “international transaction,” it must be cross border transaction. even a transaction between head Office of a Foreign Company outside India and its ae in india may get covered. a transaction between a pe of a foreign Company in india and its ae in in- dia (say, subsidiary of such foreign Company) may also get covered. even a transaction between two non residents giving rise to taxable income under the ita may get covered. on the other hand, transaction between two resident aes will fall outside the scope of the term “international transaction,” e.g. a transaction between an indian Bank and its foreign Branch though regarded as transaction between two aes, the same will not be regarded as “interna- tional transaction” since the same is between two resident enterprises. – [Section 92B(1)]

3.16. A deeming fiction has also been provided to treat even a transaction between one enterprise and another unrelated enterprise (which is not ae) as a transaction entered in to between two aes in a case where there exists a prior agreement between the ae of the enterprise and the unrelated enter- prise in relation to the transaction entered into with such unrelated enterprise or the terms of the rel- evant transaction are determined in substance be- tween such ae and the unrelated enterprise. para 55.8 of the CBDT Circular no.14 of 2001 explains this with an illustration of a case where a resident enterprise exports goods to unrelated persons abroad and there is a separate agreement or an arrangement between such unrelated person and an AE of the resident enterprise which influences the price at which those goods are exported. such a transaction will also be regarded as “international transaction” though the same is entered into with unrelated enterprise by virtue of this deeming fiction provided in the act. it seems that the deeming fiction is attracted only in a case where there exists a prior agreement in relation to the relevant transaction between the unrelated party and such ae. other transactions with such unrelated party would not get covered within the scope of the term “inter- national Transaction.” – [Section 92B(2)]

3.17. The Finance Act, 2012 has now expanded the definition by bringing in specific transactions. The trans- actions that are covered now include purchase, sale, transfer or lease of various kinds of tangible and intangible properties; various modes of capital financing; provision of services; and business re- structuring or reorganisation transactions. further, as per the revised definition, business restructuring transactions include all transactions, whether they have a bearing on profit or loss or not, either at the time of the transaction or at any future date. this has been done in light of recent judicial precedents in Dana Corporation ([2010] 186 Taxman 00187 (AAR)), Amiantit International Holding Ltd. ([2010] 189 taxman 00149 (aar)), Vanenburg Group B.V. (289 itr 464), which held that transfer pricing provisions cannot apply in a case where there is no impact on profit or loss or income.

3.18. The term ‘international transaction’ included transactions in the nature of purchase, sale or lease of intangible property. The term ‘intangible property’ was not defined. The term ‘intangible property’ has now been defined and expanded to a large extent, by including various types of intangible properties related to marketing, technology, artistic, data processing, engineering, customer, contract, human capital, location, goodwill, and any similar item which derives its value from intellectual content rather than physical attributes.

3.19. Presently, transactions entered with an unrelated person is deemed as a transaction between associ- ated enterprises if there exists a prior agreement in relation to such transaction between such unrelated person and an associated enterprise or the terms of the relevant transaction are determined in substance between such unrelated person and the associated enterprise the present provisions do not provide whether or not such unrelated person should also be a non-resident. The Finance act, 2014 has amended such transaction deemed to be an international transaction irrespective of whether such unrelated person is a resident or non-resident as long as either the enterprise or the associated enterprise is a non-resident.

? Arm’s length Price (ALP)

3.20. As stated earlier, the ultimate object of the new pro- visions is to ensure that the “international transac- tions” between aes take place at the alp so that the interest of the revenue is safeguarded and the Country gets its due share of taxes from the income arising in such transactions.

3.21. The methods for determination of ALP are specifi- cally provided. for this purpose, the alp in relation to “international transaction” is required to be de- termined by selecting the most appropriate method out of the following methods:

a) Comparable Uncontrolled Price Method (CUP) – the Cup method compares the price charged for a property or service transferred in a controlled transaction to the price charged for a comparable property or service transferred in a comparable uncontrolled transaction in com- parable circumstances.

b) resale Price Method (RPM) – the resale price method is used to determine the price to be paid by a reseller for a product purchased from an associated enterprise and resold to an independent enterprise. the purchase price is set so that the margin earned by the reseller is sufficient to allow it to cover its selling and operating expenses and make an appropriate profit.

c) Cost Plus Method (CPM) – the Cost plus meth- od is used to determine the appropriate price to be charged by a supplier of property or services to a related purchaser. the price is determined by adding to costs incurred by the supplier an appropriate gross margin so that the supplier will make an appropriate profit in the light of market conditions and functions performed.

d) Profit Split Method (PSM) – Profit-split methods take the combined profits earned by two related parties from one or a series of transactions and then divide those profits using an economically valid defined basis that aims at replicating the division of profits that would have been anticipated in an agreement made at arm’s length. arm’s length pricing is therefore derived for both parties by working back from profit to price.

e) Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM) – these methods seek to determine the level of profits that would have resulted from controlled transactions by reference to the return realised by the comparable independent enterprise. the TNMM determines the net profit margin rela- tive to an appropriate base realised from the controlled transactions by reference to the net profit margin relative to the same appropriate base realised from uncontrolled transactions.

f) Any other method as may be prescribed – recently vide Circular dated 23rd may, 2012 the CBdt has prescribed a sixth method, i.e., rule 10aB for computation of the arm’s length price operative from 1st april, 2012 and applicable from assessment year 2012-13. for analytical purposes, the new method may be split into two parts:

i. any method which takes into account the price which has been charged or paid; or

ii. any method which takes into account the price which would have been charged or paid

The first part refers to a price that has actually been charged or paid and in that sense necessitates the ex- istence of a real or actual same or similar uncontrolled transaction. this is similar to the existing Cup method though broader in scope. the second part – ‘or would have been charged or paid’ – is more significant with wider ramifications.

3.22. The above referred methods hereinafter are referred to as Specified Methods. Out of the above referred five Specified Methods, the Most Appropriate method is required to be selected having regard to the nature of the transaction, class of transactions or aes, functions performed by such persons or such other relevant factors as may be

prescribed. -[Section 92C(1)]

3.23. For the purpose of determining the alp and selecting the most appropriate method out of the Specified Methods for the International Transac- tions, rules 10B and 10C are relevant.

3.24. Each of the Specified Methods and the manner of determining alp under each one of them has been provided in the Rules. Each of the Specified Methods has been explained and it is also provided that the differences, if any, between the comparable uncontrolled prices/transactions and the relevant transaction should be determined and such dif- ferences should be adjusted to arrive at the alp.

– [Rule 10B(1)]

3.25. Since under each of the Specified Methods, primar-ily, the alp is required to be determined by making comparison with the uncontrolled prices/transactions, necessary general criteria have also been given in the rules to enable the entity as to how to judge the comparability of uncontrolled transactions with the “international transaction.” effec- tively, these criteria are based on general economic and commercial sense approach and the same will have to be used while determining such compara- bility e.g. for determining comparability of transac- tion, the terms and conditions of both the transac- tions also will have to be the same and if there is any difference between the same, the necessary adjustments will have to be made in respect of such difference. – [Rule 10B(2)]

3.26. It has also been specifically provided that the un- controlled transaction shall be treated as compa- rable with the “international transaction” if the dif- ference between the two are not likely to materially affect the price, or cost, charged or paid etc. in such transaction in the open market or alternatively, reasonably accurate adjustment can be made to elimi- nate the material effect of such difference. this, in effect, provides that the uncontrolled transaction ultimately has to be commercially comparable either without material differences or with reasonably accurate adjustments for such differences with the “International Transaction.” – [Rule 10B(3)]

3.27. It has also been provided that for the purpose of determining the comparability of uncontrolled transaction with the “international transaction,” the data relating to the financial year of the “International transaction” should be used to analyse the comparability with the uncontrolled transaction. under certain circumstances, the data of earlier two financial years can also be used for this purpose. – [Rule 10B(4)]

? Most appropriate method

3.28.Since the alp is required to be determined on the basis of the most appropriate method out of the Specified Methods, the basis of selection of the most appropriate method and the manner of appli- cation of the method so selected have also been prescribed in Rule 10C. – [Section 92C(2)]

3.29. It is provided that the most appropriate method shall be selected considering the facts and cir- cumstances of “international transaction” where the same becomes the basis for determining the most reliable measure of alp in relation to rel- evant “international transaction.” for the purpose of making such selection, necessary general crite- ria have also been given in the rules. such crite- ria are primarily based on general economic and commercial common sense approach and also on availability of reliable data, the degree of compa- rability between the “international transaction” and uncontrolled transactions as well as between the enterprises entering into such transactions etc. – [Rule 10C(2)]

3.30. A specific provision has also been made that while determining the alp by applying the most appropri- ate method, if the variation between alp determined and price at which the international transaction has actually been undertaken does not exceed 3 %, the price at which the international transaction has actually been undertaken shall be deemed to be alp. it may be noted that this provision will be applicable only where more than one price is determined un- der the most appropriate method and not in cases where different prices are determined under different Specified Methods.- [Proviso to section 92C(2)]

? Determination of ALP by the assessing officer (AO)

3.31. power has also been given to the ao to determine alp other than the alp determined by the assessee under certain circumstances. the ao is empowered to determine such alp where, on the basis of material, information or document in his possession, the ao is of the opinion that :

• the price charged or paid in an “International Transaction” or sdt has not been determined in accor- dance with section 92C(1) and(2); or

• the prescribed information and document have not been kept and maintained by the assessee; or

• the information or data used in computation of ALP is unreliable or incorrect; or

• the assessee has failed to furnish within 30 days (or extended period of further 30 days) the required information or document.

3.32. The AO can determine such alp only under the above referred circumstances. in this context, the CBDT has clarified that the AO can have recourse to section 92C(3) only under the circumstances enumerated in the section and in the event of mate- rial information or document in his possession on the basis of which an opinion can be formed that any such circumstance exists. In other cases, the value of international transaction should be ac- cepted without further scrutiny [Cir No. 12 dated 23-08-2001]. Therefore, the onus will be on the ao to prove the existence of any of the above circumstances which should become the basis of forming his opinion and he has to be in possession of some relevant material or information or document for the same. – [Section 92C(3)]

3.33. It has been specifically provided that the AO should give proper opportunity of being heard to the as- sessee before determining the alp under the above referred provisions. for this purpose, the ao should also disclose the material or information or docu- ment on the basis of which he proposes to exercise his power u/s. 92C(3) and determine the alp. it seems that even if there is no such specific provi- sion, the ao will have to give such opportunity and disclose the material etc. on which he proposes to rely. there can be some debate as to whether and extent to which the information etc. in respect of other assessees in possession of the ao can be disclosed to the assessee on account of the requirement of confidentiality to be maintained in respect of such information gathered by him in respect of other assessees. However, if the ao decides to use the same, the principle of natural justice demands that sufficient information etc. Pertaining to such other assessee will have to be provided to the assessee to enable him to properly explain and defend his case. Of course, the basic issue is still under debate as to whether the material or information or document received or collected by the ao in respect of one assessee, say mr. a, (either in the course of determining alp of mr. a or otherwise) can at all be used for the purpose of determining the alp u/s. 92C(3) of another assessee, say mr. B. this issue merits consideration because Mr. B would never have had any material information about the transactions of Mr. A at the time when Mr. B had determined the transfer prices between himself and his associated enterprises. – [Proviso to section 92C(3)]

3.34. Once the alp is determined by the ao by exercis- ing his power u/s. 92C(3), he may compute the total income of the assessee having regard to such ALP. It has also been specifically provided that no deduction u/s.10a/10aa/10B or under Chapter Via shall be allowed in respect of the increase in the total income on account of determination of such alp. It may be noted that the ao will not make any adjustment which results in decrease in the total income (or increase in the loss) because of provi- sions contained in section 92(3). – [Section 92C(4) and first Proviso thereto]

3.35. A specific provision has also been made to prohibit any corresponding adjustment in the hands of the recipients of income where any downward adjust- ment is made in the alp in respect of any payment under the above referred provisions where the tax was deducted or deductible under Chapter XViiB e.g., a royalty at the rate of 5% is paid by a ltd. (resident) to B ltd. (non-resident) treating the same as the alp and the tax is deducted while making such payment to B ltd. if in this case, the ao determines the alp at 4% in respect of such royalty by exercising his power u/s. 92C(3), then, the income of the B ltd., in respect of such royalty shall not be recomputed at 4%. however, in this context, one may consider whether recourse can be taken to the relevant treaty for seeking such recomputation. – [2nd Proviso to section 92C(4)]

3.36. Use of multiple year data for comparability analysis Presently, the Indian transfer pricing regulations allow the use of single year data for comparability analysis and multiple year data in exceptional cases

The Income Tax rules, 1962 has been amended vide Finance act, 2014 to introduce the regulations to allow use of multiple year data for comparability analy- sis. rules to be issued on this aspect.

3.37. Inter-quartile range

In India, aLP is determined as the arithmetic mean of the range of prices/margins leading to disputes in majority of the cases. It is a fact that no comparable enterprise can operate at the exactly at the identical level of comparability as the taxpayer/comparables so as to transact at the same price or earn the same margin. Moreover, there are limitations in information available of the comparables and some comparability defects remain that cannot be identified and adjusted. Computing of arithmetic mean as an average of the prices/margins obviously gets distorted by the extreme values and hence does not give a true arm’s length price/margin.

Tax payers as well as tax administrators have gained significant understanding and learning in the data analysis and for the benchmarking processes.

The Finance act, 2014 has introduced the con- cept of inter-quartile range, an internationally accepted concept of range to enhance the reliability of the analysis which includes a sizable number of comparables (statistical tools that take account of central tendency to narrow the range) of such prices/margin will be a step in right direction. This will also reduce disputes at the assessment stage itself.

? Transfer Pricing officer (TPO)

3.38. Since specialised knowledge and expertise is re- quired for the purpose of verification and/or deter- mination of ALP, a specific cell is created in the De- partment to deal with major transfer pricing cases. accordingly, the power has been taken by the Gov- ernment for assigning the job of verification or determination of the alp u/s. 92 C and documentation u/s. 92D to specified categories of officers called as tpo who could be a jt. Commissioner or dy. Commissioner or asst. Commissioner of income- tax authorised by the Board. – [Explanation to

section 92Ca]

3.39. In the last few years, the Government of india has taken many steps in order to strengthen the transfer pricing (taxation) regime in india. a series of amendment has been introduced in order to enhance the ambit of tax base and consequent increase in the revenue. the latest step in this direction was the extension of the transfer pricing provisions to Specified domestic transaction w.e.f. 01-04-2012. another area in which the government achieved considerable success was widening of the scope of the pow- ers of Transfer Pricing Officer. The basic intention of this article is to highlight the latest development that has resulted in strengthening of the powers of the Transfer Pricing Officers along with a summary discussion on section 92 Ca of ita.

3.40. Section 92Ca deals with role tpo under the trans- fer pricing regime. according to section 92 Ca, the assessing officer (AO) may refer the computation of the arm’s length price (alp) u/s. 92C to the tpo if he considers it necessary and expedient and an approval of the commissioner has been obtained.

section 92 CA also casts an obligation on the tpo to provide an opportunity of being heard to the assessee. tpo shall serve a notice to the assessee requiring him to produce (or cause to be produced) on a specified date, any evidence on which the assessee may rely in support of the calculation made by him of the alp in relation to the international transaction. a distinction has to be drawn while interpreting this section with reference to section 92C (3), wherein the ao is obliged to disclose the method adopted by him to compute alp in the show cause notice issued to the assessee but where the ao is referring the computation of alp to tpo, he is not required to disclose the reason for such refer- ring to the assessee. after conducting the hearing and taking into consideration all the relevant facts, the tpo shall by order in writing determine the alp in relation to the transaction in accordance with the provision of section 92C (3) and send a copy of his order to the ao and the assessee. on receipt of the order, the ao shall proceed to compute the total income of the assessee u/s. 92C (3) having regard to the alp determined by the tpo.

3.41. Where any other international transaction other than an international transaction referred under 92Ca(1), comes to the notice of tpo during the course of the proceedings before him, tpo shall apply as if such other international transaction is an international transaction referred to him under 92CA(1). [Section 92CA(2A)]

Where in respect of an international transaction, the assessee has not furnished the report u/s. 92e and such transaction comes to the notice of tpo during the course of the proceeding before him, tpo shall apply as if such transaction is an international transaction referred to him under 92CA(1). [Section 92Ca(2B)]

The Assessing Officer is empowered to either to assess or reassess u/s. 147 or pass an order enhancing the assessment or reducing a refund already made or otherwise increasing the liability of the assessee u/s. 154, for any assessment year, proceedings for which have been completed before the 1st day of July, 2012. [Section 92CA(2C)]

3.42. The Finance Act, 2014 has been amended to ex- tend the power to levy a penalty of 2% of value of international transaction or SDT for failure to furnish information or documentation under 92D(3) of ITA.

? Maintenance of information and documents

3.43. A specific provision has been made requiring every person who has entered into “international transaction” to keep and maintain the prescribed information and documents. such information and documents should be, as far as possible, contem- poraneous and should exist by the date specified for the submission of report u/s. 92F [i.e., due date of furnishing return of income u/s. 139(1)]. it has also been provided that fresh documentation need not be maintained separately in respect of each previous year in cases where an “international transaction” continues to have effect over more than one previous year so long as there is no sig- nificant change in the nature or terms thereof, other factors having influence on the transfer price, etc. such information and documents are required to be kept and maintained for a period of eight years from the end of the relevant assessment year. relaxation has also been provided from the requirements of keeping and maintaining such information and documents in cases where the ag- gregate value of “international transaction” entered into by the assessee in the previous year does not exceed rupees one crore (i.e., small cases). however, in such small cases, the assessee is still required to substantiate that income arising from such transaction has been computed having regard to the ALP. – [Section 92D(1) and (2) read with rule 10d(2)/(4)/(5)]

3.44. The assessee is required to keep and maintain various information and documents as provided in the rule 10d. such information and documents can be divided into two parts viz. (i) primary infor- mation and documents and (ii) supporting docu- ments. the primary information and documents required to be maintained by the assessee can be classified into three categories viz. (a) documents relating to the enterprise such as the description of ownership structure of the assessee, profile of the multinational group of which the assessee is a part etc., (b) Transaction specific documents such as the nature and terms of “international transaction”, description of the functions performed, the risks assumed and assets employed etc and (c) Computation related documents such as methods considered for determining the alp, the method selected as most appropriate method with the rea- sons for such selection, record of the actual work carried out for determining the alp, assumptions, policies and price negotiations, if any, which have critically affected the determination of the alp etc. the supporting documents would primarily include the official publications, reports, studies etc. of the Government of the country of ae or other country, market research studies, reports and technical publications of reputed institutions (national and international), price publications etc. to support the primary information and documents kept and maintained by the assessee. such information and documents should be furnished before the ao or Cit(a) as and when he requires within a period of 30 days which period can be further extended by another 30 days – [Section 92D (3) and Rule 10D(1) and (3)]

3.45. OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, in particular comparability analysis, gives importance to FAR analysis which is primarily based on residency based taxation principle developed by them and is suitable for the developed countries. In fact, the functional analysis is set on a pedestal through FAR Analysis (Functions performed, Assets em- ployed and Risks assumed). But OECD TPG pri- marily pays no heed to the importance of ‘market place’ where consumption takes place. Conversely, United Nations Model Tax Convention is sourced based and has taken into account the primary interest of developed countries’ right to tax such incomes sourced from these countries, id est, market place is recognised by UN in its Model Treaty. However this issue is not fully captured in Article 5 (Permanent Establishment) and Article 7 (Business Profits). If one looks at experience shared by India, China and Brazil, these countries want to retain justifiably their right of taxation through attribution theory by giving importance to market place. United Nations released its Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for developing countries wherein Comparability Analysis also gives importance to concepts like Location Savings, Location Specific Advantage, Location Rent and Market Premium. The experience shared by three major developing coun- tries (India, China and Brazil) will enable readers to understand the philosophy behind those concepts which are dealt in greater detail in subsequent part of the article. Therefore, in my opinion, these devel- oping countries as well as UN TP Guidance gives importance to FARM Analysis (Functions performed, Assets employed, Risks assumed and Market premium) as against FAR Analysis.

? Accountant’s Report

3.46. Every person entering into “international transac- tion” is also required to obtain and furnish a report from a Chartered accountant in form no. 3CeB on or before the specified date [viz. due date of furnishing Return of Income u/s.139(1)]. – [Sec.92E and rule 10e]

3.47. For the purpose of maintenance of the prescribed information and documents and obtaining and furnishing accountant’s report, reference may also be made to the Guidance note of the institute of Chartered accountants of india (ICAI).

? Penalty

3.48. For non-compliance with the provisions relating to transfer pricing referred to herein before, penalty provisions have been made in the ita in respect of various defaults. 3.49. as stated above, the assessee is required to keep and maintain specified information and documents in respect of international transactions. the same are also required to be produced whenever called for by the AO or the CIT(A) within the specified time limit. If the assessee fails to maintain and/or furnish such information or documents before the authorities as may be required, a penalty can be imposed of an amount equal to 2% of the value of interna- tional transaction or sdt for each such failure. it seems that once the authority is satisfied about such default, the quantum of penalty is fixed under the act. however, no such penalty can be imposed if the assessee proves that there was a reasonable cause for such failure. – [Section 271AA, Section 271G and section 273B.]

3.50. As stated above, the assessee is required to obtain and furnish a report from Chartered accountant in the prescribed form within the specified time limit. in the event of failure to comply with this requirement, without a reasonable cause, a penalty of ru- pees One lac can be imposed. – [Section 271BA and section 273B]

3.51. A penalty for concealment of income or for furnishing inaccurate particulars of income can levied under the it act of an amount equal to 100% to 300% of the amount of tax sought to be evaded by reason of the concealment of income or furnishing of inaccurate particulars of such income u/s. 271(1)(c) (‘Concealment Penalty’). A specific provision has been made to provide that if an addition is made to the total income of the assessee by ex- ercising power vested in the ao u/s.92C(3), then, for the purpose of provisions relating to Conceal- ment penalty, the amount of such addition to the total income shall be deemed to represent the con- cealed income or the income in respect of which inaccurate particulars have been furnished unless the assessee proves to the satisfaction of the ao or the Cit(a) or the Cit that the price charged or computed in the relevant international transaction was computed in accordance with the provisions contained in section 92C and in the manner prescribed under that section in good faith and with due diligence. – [Explanation 7 to section 271(1)]

? Advance Pricing Arrangements – sections 92cc anD 92cD

3.52. The taxation tug-of-war between mnes and the indian tax authorities has been a never-ending story. the transfer pricing regulations, which have been a long-drawn contentious issue between the tax authorities and mnes, recently came into the limelight after certain multinationals were slapped with hefty tax demands for allegedly entering into international transactions with their associated enterprises at non-arm’s length prices.

3.53. In each round of audit, the indian tax authorities have ventured into new controversies in areas such as marketing intangibles, share valuation, corpo- rate guarantees, business restructuring and loca- tion savings, in addition to attributing high markups for routine activities. With close to usd 10 billion of adjustments being made in the eighth round of transfer pricing audits, transfer pricing has gained paramount importance for both taxpayers and the tax authorities. With such huge adjustments, the indian tax authorities are reckoned as tough in transfer pricing matters, with india accounting for approximately 70% of all global transfer pricing dis- putes by volume.

3.54. With significant uncertainties existing in the approach of the indian tax authorities towards several complex transactions undertaken by multinationals, an advance pricing agreement (apa) programme has clearly been the need of the hour for multinationals in india. APAS appear to be the best possible solution for obtaining stability and certainty in transfer pricing matters. the apa programme is expected to introduce a whole new dimension to the transfer pricing landscape in india. With taxpayers looking for increased tax certainty, many are opting for the apa route.

3.55. APAs were first showcased as a part of the proposed direct taxes Code back in 2009 and were again mentioned in the direct taxes Code, 2010. however, with the uncertainty surrounding the introduction of the direct taxes Code, the introduction of apas was also deferred. for the highly litigious transfer pricing regime in india, this uncertainty regarding the fate of apas raised much concern amongst large taxpayers. in a much appreciated move, the ministry of finance introduced apas in the finance act, 2012.

3.56. An APA is an agreement between the tax authori- ties and the taxpayer that determines in advance the most appropriate transfer pricing methodology or the arm’s length price for covered intercompany international transactions. the indian apa regime allows multinationals to ascertain the potential price for their international transactions beforehand. Taxpayers are also relieved of many compliance obligations for a period of five years, providing taxpayers with stability and certainty with regard to their tax liability.

3.57. The tax authorities have proved their claim that the apa programme is a big success, by concluding the first number of APAs in just one year since the APA program was introduced in india. india is undoubtedly the first country in the world to achieve this success in the very first year. The tax authorities believe that the apa programme will help to avoid disputes arising from the country’s increasingly aggressive positions on transfer pricing matters.

3.58. Till now, most apa requests in india are from companies belonging to the information technology and information technology enabled services (ITES), automobile, pharmaceuticals and financial sectors, on issues that pertain to captive outsourcing centres, share valuation, the extension of corporate guarantees, royalties, management fees and interest income. these issues have been at the heart of virtually all transfer pricing disputes.

3.59. APAS offer better assurance regarding the taxpayer’s transfer pricing method. another effect is that they reduce risk and assist in the financial reporting of possible tax liabilities. apas also decrease the incidence of double taxation and costs linked with audit defence and transfer pricing documentation preparation. APAS can provide risk management, certainty, avoidance of double taxation and reduced litigation. The bilateral or multilateral approach is far more likely to ensure that the apa will reduce the risk of double taxation.

3.60. However, a significant challenge of an APA is that it relies on predictions about future events. Criti- cal assumptions should provide possible scenari- os and should be appropriately worded to ensure that an apa remains workable. the tax authorities may become privy to highly sensitive information and documentation which could present its own challenges. further, the taxpayers also need to have assurance that past closed years will not be reopened for an audit based on the transfer pricing agreed in the apa.

3.61. The success of the apa programme will be de- termined by its ability to distinguish itself from traditional audits, and to act as a means to facili- tate expedited dispute resolution for international transactions. an apa is certainly a positive step towards a more certain economy; however it is imperative for taxpayers to perform a cost-benefit analysis of all aspects before taking a step forward towards an apa.

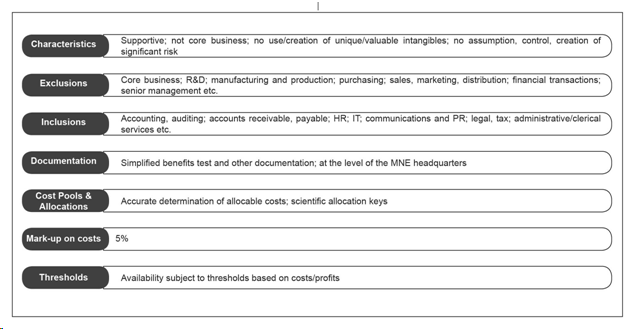

? Safe harbour rules

3.62. With the introduction of safe harbour rules, akin to the apa mechanism, taxpayers expect a reduction in litigation. However, as this is the first year for In- dia, taxpayers suffer from the ambiguity surround- ing these rules, including the following:

– As the apa option was only recently introduced in india, taxpayers will have to cleverly evaluate the two available alternatives, namely the apa mechanism or the safe harbour rules, considering the cost and time involved; and

– The eligibility of taxpayers to opt to apply the safe harbour rules is debatable as, although the eligible activities are defined, clarity is still lacking regard- ing which parties fall under those activities.

3.63. The rates indicated in the safe harbour rules are not tantamount to an arm’s length price. However, these rates are provided so as to avoid the litigation process as a whole by the indian tax authorities while jointly achieving consensus on the transfer price.

3.64. The introduction of safe harbour rules is surely a welcomed step, moving towards reducing substantial transfer pricing litigation and building a proper tax environment. Nevertheless, it would have been better if the safe harbour rules had allowed dispensation from compliance with documentation requirements.

3.65. However, from a taxpayer perspective, considering the pressures on profitability and solid competition from other jurisdictions, it might be challenging for many groups to opt to apply the safe harbour regime. It is anticipated that the assessing officer and transfer pricing officer will focus on the functions, assets and risks analysis of the taxpayer to validate the taxpayer’s eligibility to apply the safe harbour rules. Also, no time limit is prescribed within which such validation must be conducted, thereby leaving it open to experience during the time to come.

3.66. Nevertheless, considering that the markup rates are on the higher side, it would be interesting to observe the actual application of the safe harbour rules by taxpayers, more specifically whether the taxpayer opts to apply a higher markup and achieve relief from the lengthy litigation process or prefers to defend its lower markup through the existing litigation mechanisms.

4. Special Issues related to Transfer Pricing

4.1. documentation requirements

a. Generally, a transfer pricing exercise involves vari- ous steps such as:

• Gathering background information;

• Industry analysis;

• Comparability analysis (which includes functional

analysis);

• Selection of the method for determining Arm’s length pricing; and

• Determination of the Arm’s Length Price.

b. At every stage of the transfer pricing process, vary- ing degrees of documentation are necessary, such as information on contemporaneous transactions. one pressing concern regarding transfer pricing documentation is the risk of overburdening the taxpayer with disproportionately high costs in ob- taining relevant documentation or in an exhaustive search for comparables that may not exist. ideally, the taxpayer should not be expected to provide more documentation than is objectively required for a reasonable determination by the tax authorities of whether or not the taxpayer has complied with the arm’s length principle. Cumbersome documentation demands may affect how a country is viewed as an investment destination and may have particularly discouraging effects on small and mediumsized enterprises (smes). c. Broadly, the information or documents that the tax-payer needs to provide can be classified as:

1. Enterprise-related documents (for example the ownership/shareholding pattern of the tax- payer, the business profile of the MNE, industry profile etc);

2. Transaction-specific documents (for example the details of each international transaction, func- tional analysis of the taxpayer and associated enterprises, record of uncontrolled transactions for each international transaction etc); and

3. Computation-related documents (for example the nature of each international transaction and the rationale for selecting the transfer pricing method for each international transaction, computation of the arm’s length price, factors and assumptions influencing the determination of the Arm’s Length price etc).

d. The domestic legislation of some countries may also require “contemporaneous documentation.” Such countries may consider defining the term “contemporaneous” in their domestic legislation. The term “contemporaneous” means “existing or occurring in the same period of time.” different countries have different interpretations about how the word “contemporaneous” is to be interpreted with respect to transfer pricing documentation. some believe that it refers to using comparables that are contemporaneous with the transaction, regardless of when the documentation is produced or when the comparables are obtained. Other countries interpret contemporaneous to mean using only those comparables available at the time the transaction occurs.

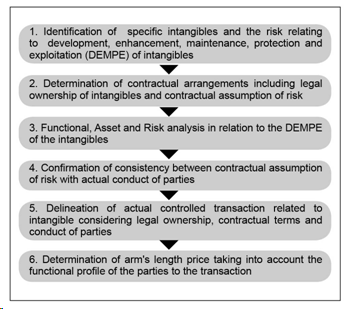

4.2. Intangibles

a. Intangibles (literally meaning assets that cannot be touched) are divided into “trade intangibles” and “marketing intangibles.” trade intangibles such as know-how relate to the production of goods and the provision of services and are typically developed through research and development. Marketing intangibles refer to intangibles such as trade names, trademarks and client lists that aid in the commercial exploitation of a product or service.

b. The Arm’s Length Principle often becomes difficult to apply to intangibles due to a lack of suitable comparables; for example intellectual property tends to relate to the unique characteristic of a product rather than its similarity to other products. this difficulty in finding comparables is accentuated by the fact that dealings with intangible property can also occur in many (often subtly different) ways such as by: license agreements involving payment of royalties; outright sale of the intangibles; compensation included in the price of goods (i.e., selling unfinished products including the know-how for further processing) or “package deals” consisting of some combination of the above.

c. The Profit Split Method is typically used in cases where both parties to the transaction make unique and valuable contributions. however, care should be taken to identify the intangibles in question. experience has shown that the transfer pricing methods most likely to prove useful in matters involving transfers of intangibles or rights in intangibles are the CUP Method and the Transactional Profit Split method. Valuation techniques can be useful tools in some circumstances.

4.3. Intra-group Services

a. An intra-group service, as the name suggests, is a service provided by one enterprise to another in the same mne group. for a service to be considered an intra-group service it must be similar to a service which an independent enterprise in comparable circumstances would be willing to pay for in-house or else perform by itself. if not, the activity should not be considered as an intra-group service under the arm’s length principle. the rationale is that if specific group members do not need the activity and would not be willing to pay for it if they were independent, the activity cannot justify a payment. Further, any incidental benefit gained solely by being a member of an mne group, without any specific services provided or performed, should be ignored.

b. An arm’s length price for intra-group services may be determined directly or indirectly — in the case of a direct charge, the Cup method could be used if comparable services are pro- vided in the open market. in the absence of comparable services the Cost plus method could be appropriate.

c. If a direct charge method is difficult to apply, the mne may apply the charge indirectly by cost sharing, by incorporating a service charge or by not charging at all. such methods would usually be accepted by the tax authorities only if the charges are supported by foreseeable benefits for the recipients of the services, the methods are based on sound accounting and commercial principles and they are capable of producing charges or allocations that are commensurate with the reasonably expected benefits to the recipient. In addition, tax authorities might allow a fixed charge on intra-group services under safe harbour rules or a pre- sumptive taxation regime, for instance where it is not practical to calculate an arm’s length price for the performance of services and tax accordingly.

4.4. Cost-contribution agreements

a. Cost-contribution agreements (CCas) may be formulated among group entities to jointly develop, produce or obtain rights, assets or services. each participant bears a share of the costs and in return is expected to receive pro rata (i.e., proportionate) benefits from the developed property without further payment. such arrangements tend to involve research and development or services such as central- ised management, advertising campaigns etc.

b. In a CCA there is not always a benefit that ulti- mately arises; only an expected benefit during the course of the CCa which may or may not ultimately materialise. the interest of each participant should be agreed upon at the outset. the contributions are required to be consistent with the amount an independent enterprise would have contributed under comparable cir- cumstances, given these expected benefits. the CCa is not a transfer pricing method; it is a contract. however, it may have transfer pricing consequences and therefore needs to comply with the arm’s length principle.

4.5. Use of “secret comparables” a. there is often concern expressed by enterprises over aspects of data collection by tax authorities and its confidentiality. Tax authori- ties need to have access to very sensitive and highly confidential information about taxpayers, such as data relating to margins, profitability, business contacts and contracts. Confidence in the tax system means that this information needs to be treated very carefully, especially as it may reveal sensitive business information about that taxpayer’s profitability, business strategies and so forth.

b. Using a secret comparable generally means the use of information or data about a taxpayer by the tax authorities to form the basis of risk assessment or a transfer pricing audit of another taxpayer. that second taxpayer is often not given access to that information as it may reveal confidential information about a compet- itor’s operations.

c. Caution should be exercised in permitting the use of secret comparables in the transfer pricing audit unless the tax authorities are able to (within limits of confidentiality) disclose the data to the taxpayer so as to assist the taxpayer to defend itself against an adjustment. taxpayers may otherwise contend that the use of such secret information is against the basic principles of equity, as they are required to benchmark controlled transactions with comparables not available to them — without the opportunity to question comparability or argue that adjustments are needed.

4.6. Controlled foreign corporation provisions

Some countries operate Controlled foreign Cor- poration (CfC) rules. CfC rules are designed to prevent tax being deferred or avoided by taxpayers using foreign corporations in which they hold a controlling shareholding in low-tax jurisdictions and “parking” income there. CfC rules treat this income as though it has been repatriated and it is therefore taxable prior to actual repatriation. Where there are CfC rules in addition to transfer pricing rules, an important question arises as to which rules have priority in adjusting the taxpayer’s returns. due to the fact that the transfer pricing rules assume all transactions are originally conducted under the arm’s length principle, it is widely considered that transfer pricing rules should have priority in applica- tion over CfC rules. after the application of transfer pricing rules, countries can apply the CfC rules on the retained profits of foreign subsidiaries.

4.7. Thin Capitalisation

When the capital of a company is made up of a much greater contribution of debt than of equity, it is said to be “thinly capitalised”. this is because it may be sometimes more advantageous from a taxation viewpoint to finance a company by way of debt (i.e., leveraging) rather than by way of equity contributions as typically the payment of interest on the debts may be deducted for tax purposes where- as distributions are non-deductible dividends. To prevent tax avoidance by such excessive leveraging, many countries have introduced rules to prevent thin capitalisation, typically by prescribing a maximum debt to equity ratio. Country tax administrations often introduce rules that place a limit on the amount of interest that can be deducted in calculating the measure of a company’s profit for tax purposes. Such rules are designed to counter cross-border shifting of profit through excessive debt, and thus aim to protect a country’s tax base. From a policy perspective, failure to tackle excessive interest payments to associated enterprises gives mnes an advantage over purely domestic businesses which are unable to gain such tax advantages.

4.8. Documentation

a. Another important issue for implementing do- mestic laws is the documentation requirement associated with transfer pricing. Tax authorities need a variety of business documents which support the application of the arm’s length principle by specified taxpayers. However, there is some divergence of legislation in terms of the nature of documents required, penalties imposed, and the degree of the examiners’ authority to collect information when taxpayers fail to produce such documents. There is also the issue of whether documentation needs to be “contemporaneous.”

b. In deciding on the requirements for such documentation there needs to be, as already noted, recognition of the compliance costs imposed on taxpayers required to produce the documentation. another issue is whether the benefits, if any, of the documentation require- ments from the administration’s view in dealing with a potentially small number of non-compliant taxpayers are justified by a burden placed on taxpayers generally. A useful principle to bear in mind would be that the widely accepted international approach which takes into account compliance costs for taxpayers should be followed, unless a departure from this approach can be clearly and openly justified because of local conditions which cannot be changed immediately (e.g. constitutional requirements or other overriding legal requirements). In other cases, there is great benefit for all in taking a widely accepted approach.

4.9. Time Limitations

Another important point for transfer pricing domestic legislation is the “statute of limitation” issue — the time allowed in domestic law for the tax administration to do the transfer pricing audit and make necessary assessments or the like. since a transfer pricing audit can place heavy burdens on the taxpayers and tax authorities, the normal “statute of limitation” for taking action is often extended compared with general domestic taxation cases. however, too long a period during which adjustment is possible leaves taxpayers in some cases with potentially very large financial risks. Differences in country practices in relation to time limitation may lead to double taxation. Countries should keep this issue of balance between the interests of the revenue and of taxpay- ers in mind when setting an extended period during which adjustments can be made.

4.10. Lack of comparables

One of the foundations of the arm’s length princi- ple is examining the pricing of comparable transactions. Proper comparability is often difficult to achieve in practice, a factor which in the view of many weakens the continued validity of the principle itself. the fact is that the traditional transfer pricing methods (Cup, rpm, Cp) directly rely on comparables. these comparables have to be close in order to be of use for the transfer pricing analysis. It is often extremely difficult in practice, especially in some developing countries, to obtain adequate information to apply the arm’s length principle for the following reasons:

1. There tend to be fewer organised operators in any given sector in developing countries; finding proper comparable data can be very difficult;

2. The comparable information in developing countries may be incomplete and in a form which is difficult to analyse, as the resources and process- es are not available. in the worst case, information about an independent enterprise may simply not exist. Databases relied on in transfer pricing analysis tend to focus on developed country data that may not be relevant to developing country markets (at least without resource and informa-tion-intensive adjustments), and in any event are usually very costly to access; and

3. Transition countries whose economies have just opened up or are in the process of opening up may have “first mover” companies who have come into existence in many of the sectors and areas hitherto unexploited or unexplored; in such cases there would be an inevitable lack of comparables.

Given these issues, critics of the current transfer pricing methods equate finding a satisfactory comparable to finding a needle in a haystack. Overall, it is quite clear that finding appropriate comparables in developing countries for analysis is quite possibly the biggest practical problem currently faced by enterprises and tax authorities alike.

4.11. Lack of knowledge and requisite skill-sets

Transfer pricing methods are complex and time- consuming, often requiring time and attention from some of the most skilled and valuable human re- sources in both mnes and tax administrations. transfer pricing reports often run into hundreds of pages with many legal and accounting experts employed to create them. this kind of complexity and knowledge requirement puts tremendous strain on both the tax authorities and the taxpayers, espe- cially in developing countries where resources tend to be scarce and the appropriate training in such a specialized area is not readily available. their transfer pricing regulations have, however, helped some developing countries in creating requisite skill sets and building capacity, while also protecting their tax base.

4.12. Complexity

a. Rules based on the arm’s length principle are becoming increasingly difficult and complex to administer. transfer pricing compliance may in- volve expensive databases and the associated expertise to handle the data. transfer pricing audits need to be performed on a case by case basis and are often complex and costly tasks for all parties concerned.

b. In developing countries resources, monetary and otherwise, may be limited for the taxpayer (especially small and medium sized enterprises (smes)) which have to prepare detailed and complex transfer pricing reports and comply with the transfer pricing regulations, and these resources may have to be “bought-in.” similarly, the tax authorities of many developing countries do not have sufficient resources to examine the facts and circumstances of each and every case so as to determine the acceptable transfer price, especially in cases where there is a lack of comparables. Transfer pricing audits also tend to be a long, time consuming process which may be contentious and may ultimately result in “estimates” fraught with conflicting interpretations.

c. In case of disputes between the revenue authorities of two countries, the currently available prescribed option is the mutual agreement procedure as noted above. This too can possibly lead to a protracted and involved dialogue, often between unequal economic powers, and may cause strains on the resources of the companies in question and the revenue authorities of the developing countries.

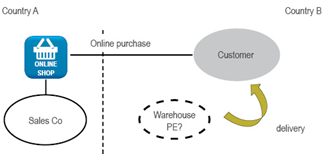

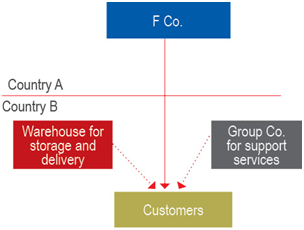

4.13. Growth of the “e-commerce economy”

a. The internet has completely changed the way the world works by changing how information is exchanged and business is transacted. physical limitations, which have long defined traditional taxation concepts, no longer apply and the application of international tax concepts to the internet and related e-commerce transac- tions is sometimes problematic and unclear.

b. The different kind of challenges thrown up by fast-changing web-based business models cause special difficulties. From the viewpoint of many countries, it is essential for them to be able to appropriately exercise taxing rights on certain intangible-related transactions, such as e-commerce and web-based business models

4.14. Location savings

a. Some countries like China, india and other developing countries are taking the view that the economic benefit arising from moving operations to a low-cost jurisdiction, i.e., “location savings”, should accrue to that country where such operations are actually carried out.

b. Accordingly, the determination of location sav- ings, and their allocation between the group companies (and thus, between the tax authori- ties of the two countries) has become a key transfer pricing issue in the context of developing countries. unfortunately, most interna- tional guidelines do not provide much guidance on this issue of location savings, though they sometimes do recognise geographic conditions and ownership of intangibles. The us section 482 regulations provide some sort of limited guidance in the form of recognising that adjustments for significant differences in cost attributable to a geographic location must be based on the impact such differences would have on the controlled transaction price given the relative competitive positions of buyers and sellers in each market. the OECD Guidelines also consider the issue of location savings, emphasising that the allocation of the savings depends on what would have been agreed by independent parties in similar circumstances.

c. The un tp manual states that arm’s length attribution of location savings depends on the competitive factors relating to the access of location specific advantages and on the realistic alternatives available to the associated enterprises (aes) given their respective bargaining power.