INTRODUCTION

The internet revolution followed with the insurgence of mobility solutions has triggered an unprecedented growth in the e-commerce industry. Initially, emerging as a mere mediator of commercial transactions, e-commerce has now engulfed the entire traditional buy-sell and service delivery model into its wave. The start-up culture with its unconventional business models has further thrusted the steep degeneration of physical interface in commercial transactions. Moreover, with FDI limitations in multi-brand retail/ecommerce inventory trading, innovative techniques have crept into the transaction system. This has resulted in peculiar GST issues which are dealt with in the present article.

BUSINESS MODELS IN E-COMMERCE

E-commerce has been understood as buying and selling goods or services including digital products over digital or electronic network. The typical business models alive in the industry are:

Inventory Model: The operator owns and operates both the electronic platform as well as the inventory for supply of goods/services. He engages into a traditional buy-sell relationship with the end consumer (e.g. Brand Webstores).

Market Place Model: The FDI policy restriction has germinated this model for foreign PE funded companies in e-commerce retail space. The operator only owns the platform and provides ancillary functions in the form of logistics, packaging, collection and customer support. He does not own the inventory and projects itself as a platform where buyers and sellers transact with each other (e.g. Amazon/Flipkart). Sub-variants include aggregator of market-place (such as Trivago) which host multiple web platforms on one platform, akin to super-market place.

Aggregator Model: This is a variant of the market-place model where the operator plays a significant role in monitoring, influencing and pricing the commercial transaction (e.g. Uber). Not only does the aggregator perform a platform service but it also projects itself as a pseudo-service provider to the end customer.

Conversational Model: Social media platforms have made it possible for e-commerce companies to sell their products from their posts. Using this method, consumers are able to shop directly from their newsfeed. One could equate them with a super-market place assisting the market place in procurement of orders.

Each of these variants raise certain intriguing GST issues which have been addressed in the later part of the article.

LEGAL PROVISIONS ON E-COMMERCE

E-Commerce transactions are commercial transactions that take place through electronic networks. In legal sense, the terminology is with reference to ‘supply’ transactions which are executed over the internet network:

(44) “electronic commerce” means the supply of goods or services or both, including digital products over digital or electronic network;

(45) “electronic commerce operator” means any person who owns, operates or manages digital or electronic facility or platform for electronic commerce;

The phrase e-commerce has been adopted in two provisions: (a) section 9(5): ‘Tax shift mechanism’ where GST is being imposed on the E-commerce operator (ECO) as a deemed supplier of the services (Uber/Ola, etc); (b) section 52 – ‘Tax collection at source’ in cases where the e commerce operator is collecting payments on behalf of suppliers for orders received and fulfilled through the e-commerce portal, such an operator retains a portion of the sale proceeds as TCS which is deposited to the Government treasury (Amazon/ Flipkart, etc).

RATES/EXEMPTIONS INFLUENCED BY THE E-COMMERCE BUSINESS

Rate/exemption notifications have been customised for businesses operating under the ecommerce model. Some of them are:

– Entry 23 and 25 provide for taxation of house-keeping services (such as plumbing, carpentering, etc) classifiable under SAC 9985 and 9987 when supplied through an ECO provided input tax credit has not been availed, even though the individual suppliers are below taxable threshold limits and otherwise not taxable;

– Entry 17 and 15 provides for exemption to transportation of passengers in specified cases. But the exemption is not available if the service is supplied through ECO who is liable to pay tax under section 9(5)

SCOPE OF THE TERM ‘E-COMMERCE’ & ‘E-COMMERCE OPERATOR’

E-commerce supplies are generally contracted online but are performed/delivered either in on-line or off-line mode depending on the nature of supply and the customer requirements –variations are tabulated below:

| Contractual Mode |

Performance/Delivery | Payment | Example |

| Offline | Online | Online | Banking services |

| Online | Online | Online | NetFlix |

| Online | Offline | Offline/Online | Amazon |

| Offline | Offline | Online | UPI transactions |

The narrow issue under consideration is whether adoption of electronic mode is with respect to the contractual mode (for ease we call it ‘contractual supply’) or with reference to mode of performance/ delivery (‘performed supply’). There is absolutely no doubt in cases where both events (i.e. contract to performance) takes place over digital networks; the doubt arises where either one of the commercial elements takes place through physical mode. This debate leads us to (a) basics of supply; (b) the meaning of the phrase supply ‘over digital network’; and (c) contexts in which this phrase is used in the GST scheme.

SUPPLY IS CONTRACTUAL OR PERFORMANCE DRIVEN?

Taking a step back to the charging provisions, the scope of supply under section 7 is: sale, transfer, barter, exchange, license, rental, lease or disposal. These are legally recognized contracts with an obligation on the supplier for performance of certain acts. As a noun, it would refer to the genre of contract and the interpretation would tilt towards the ‘contractual supply’ rather than the ‘mode of performance’. The scope of supply also uses the phrase ‘made or agreed to be made.’ This implies that the scope of supply would stand with reference to the mode of agreement. If this is to be juxtaposed into the above analysis, it appears that supply is triggered the moment a contract comes to birth, and is not prolonged until performance/ delivery.

Alternatively, if supply is understood as a verb, then one would understand it to involve the actual performance obligations undertaken by the supplier. Traditionally, supply involved performance of obligations and counter obligations e.g. sale involves a transfer of property in goods for consideration; services in the nature of lease, license, etc, involve the promise of grant of use of a premises in consideration for a consideration. Historically, Courts have concurred that tax on services is on ‘rendition of service.’1 Mere agreements for sale were not considered as taxable events under the ambit of sales tax law.2 The GST law should not deviate on the fundamental principle that mere agreements should not form basis for imposing a tax levy. Though the tax may be collectible on advances or agreements, the said liability crystallises only on performance of the supply (i.e. rendition of service or sale of goods). While this is a debated topic, some implicit cues from the Government’s own circulars may indicate that performance is a necessary ingredient of supply:

– Circular3 on liquidated damages states that ‘performance is the essence of a contract’ and non-performance results in loss/damages which is not intended to be taxed, thus implying that without performance tax may not be imposable;

– The circular4 on fake invoicing also states that the person merely issuing bills is not to be subjected to tax but only penalty in the absence of a supply a.k.a. movement of goods;

– Section 34 provides for issuance of credit notes for reversal of tax payments on account of tax charged being in excess of tax payable, which includes cases where supply is not performed;

– Circular5 indicates eligibility of refund on advances for cancelled contracts where supply was not performed.

1. AL&FS v/s. UOI 2010 (20) S.T.R. 417 (S.C.) & AIFTP v/s. UOI 2007 (7) S.T.R. 625 (S.C.) 2. 1954 (5) TMI 17 SC Sale Tax officer vs.. Budh Prakash Jai Prakash 3. No. 178/10/2022-GST 3-8-2022 4. No. 171/03/2022-GST 6-7-2022 5. No. 137/07/2020-GST 13-4-2020

If performance is the basis of understanding supply, the definition of E-commerce should be apply only where ‘performance’ is over digital network rather than mere contracting over digital network. The consequence of these two extremes is laid down for better understanding:

SUPPLY ‘OVER’ E-COMMERCE – WIDE INTERPRETATION OF CONTRACTING USING DIGITAL NETWORK

Toeing the wide interpretation of supply to refer to ‘contractual supply’, ECOs, who facilitate digital communications and order confirmations through digital networks, would be covered and subjected to E-commerce provisions. In real-world scenarios the following could be classifiable as E-commerce transactions:

| Contract Mode | E-commerce operator | Performance | Example | Classification |

| Internet service provider (ISP) | Physical | All transactions |

E-commerce | |

| Telephonic | Telecom service provider (TSP) | Physical | ||

| Web-portal | ISP | Physical |

In today’s digital era all communications/contracts which take place over digital network would be engulfed into this wide interpretation. The only transaction which would be excluded would be the ones which take place over the counter. Consequently, all ISP/TSPs would be conferred as the ECOs and provisions of section 52 could be said to apply to all such transactions which are settled through their online systems. Section 24 would then mandate everyone to compulsory obtain registration without applying the threshold limit in which case the threshold limit of 20 lakhs would become a dead letter. Is this the probable intention of the law? We will hold onto the conclusion until examining other forms of interpretation.

SUPPLY ‘OVER’ E-COMMERCE – NARROW INTERPRETATION

Paying attention to the phrase ‘over’, it appears that the same has been used as an ‘adverb’ to the function of supply (which can be understood as a verb – refer supra). As an adverb to the verb, dictionaries indicate that the term represents a passage or trajectory over which the act is performed. The emphasis in the definition is then on the actual ‘performance’ of the supply obligations (refer discussion above) over digital networks. A narrow interpretation would demand that the definition of e-commerce would be applicable only for digital goods and services performing or passing through the digital network and cannot extend to physical world supplies even-though the agreement or order took place over the digital network. Unless and until the supply i.e. performance takes place over digital network (which is possible only for digital products and/or services), it would not amount to an ecommerce transaction. In the absence of a regulatory supervision, an appointment of an intermediary in the web of digital services would assist the Government in collecting the TCS and building a ‘crawler’ mechanism to identify the supplier in the digital format.

In contradistinction, supplies of goods through Amazon/Flipkart, where the delivery takes place at the doorstep, cannot be considered as an E-commerce transaction. Narrow interpretation demands that supply is performance driven and not merely contract driven i.e. sale and physical delivery should also take place over digital network. Online marketplaces perform services of displaying the product, recording orders, receipt of payment and coordinating the logistics. The subject-matter of contract performance is taking place in the real world through physical performance and hence one may contend that Amazon/Flipkart not falling within the GST understanding of ‘e-commerce’.

SUPPLY ‘OVER’ E-COMMERCE – REASONABLE INTERPRETATION

Naturally, the above views would face immediate resistance on perception as well as legality. The three-fold challenge would be (a) the context of the phrase (section 9(5) or 52 of GST law) encompass cases where even mere agreement or arrangement of the supply takes place through digital network – the very operation of ‘Tax shift’ or ‘TCS mechanism’ is linked to the core function of e-commerce being a facilitator of supply rather than engaging in performance itself; (b) the definition of e-commerce operator signifies a role distinct from that of a supplier, as one who owns, operates or manages a digital network for e-commerce transaction and does not extend to performing the subject supply. It also includes digital products and services separately implying that non-digital supplies would also be covered in the initial part of the definition; (c) FAQs and other government material suggests that Ecommerce operators like Amazon/ Flipkart are intended to be covered in this model and no indication has been made to narrow the scope to digital goods/ services only.

While on one hand, the wide interpretation of E-commerce results in the inclusion of all possible transactions as e-commerce, leaving none out of its fold, narrow interpretation limits inclusion only of digital products or services that are completely performed over electronic network, hence leaving the popular transactions over Amazon/ Flipkart outside its fold, making the other substantive provisions (TCS/ Tax-shift) very limited in operation. Naturally, this confusion would guide us onto a balanced interpretation on following contextual reasons:

– For tax shift mechanism to function under section 9(5), one needs a de-facto supplier which is then substituted with an ECO as a de-jure supplier (refer discussion below) – simple objective being administrative convenience to collect the same from a single point who aggregates all the supplies under an umbrella;

– TCS mechanism (including GSTR-8) is aimed at collecting taxes at the source of a supplier performing supplies of goods or services and receiving the payments through the ecommerce portal though tax is finally payable by the supplier;

Both these contexts indicate that e-commerce is intended to be a mediator of supplies wherein three parties must be necessarily involved. Where the e-commerce operator is the performer of supply itself (such as NetFlix), such transactions would stand excluded from TCS mechanism in the absence of a third party. Unless pure digital supplies are routed through online aggregators TCS provisions should not be invoked. This view also synchronises well with the amendments in GSTR-3B form in table 3.1.1 where separate tables have been now provided for reporting the taxable supplies at both points (a) at the ECO through whom the supplies have been performed under section 9(5) (b) exclusions of the corresponding value at the registered person’s end who performs the supplies through ECO under section 9(5). The industry appears to have accepted this reasonable view and implemented the law accordingly.

TAX SHIFT MECHANISM – SECTION 9(5)

E-commerce operators operating as ‘aggregators’ are governed by the Tax Shift mechanism under section 9(5). This section states that the e-commerce operator is liable to tax on specified categories of services (presently cab travel, accommodation, house-keeping, restaurant services). The e-commerce operator is deemed as a supplier (‘deemed supplier’) instead of the de facto supplier and consequently all provisions applicable to the suppliers extend even to the ecommerce operator. There is a stark difference between the reverse charge mechanism specified in section 9(3)/(4) and the said tax-shift mechanism under section 9(5). Reverse charge provisions fixes the ‘recipient’ of a supply (possessing contract privacy) to discharge the tax liability. Moreover, since this tax liability is not an output tax for the recipient, it has to be necessarily discharged through cash payment rather than input tax credit.

On the contrary, the tax shift mechanism fixes the tax liability onto a third party i.e. beyond contracting parties (i.e. supplier and recipient). It is intended to apply where an e-commerce platform aggregates all the suppliers and recipients (‘Aggregator’) and the parties formalize their agreement through the e-commerce aggregator. Since the aggregator is a central database of all agreements executed through it, the administration thought it fit to fix the liability (of otherwise unorganized service providers) on the e-commerce operator.

Therefore, by legislative choice the e-commerce operator, though an intermediary in the transaction is placed into the shoes of the supplier for GST purposes.

Now this tax shift scheme does not have a separate code. It operates within the entwines of regular provisions as applicable to other suppliers. Hence, all provisions should be read as applying to the e-commerce operator performing the supply of goods itself. Consequently, statutory responsibilities otherwise entrusted on the de-facto suppliers are now placed onto the ECO i.e. (a) ascertainment of character of inter-state/intra-state supplies (b) classification and/or rate of tax – composite/ mixed supply (c) fixation of time and value of supply (d) claim of input tax credit (e) discharge of output tax liability (f) apply for refunds (if any), etc. Consequently, all legal actions would operate against the ECO de-hors the taxable status of the actual supplier who performed the service – for example, revenue action would be taken on Uber for all rides booked through its application even-though the actual cab service was rendered by unregistered/non-taxable individual cab-driver to the passenger.

INPUT TAX UTILISATION FOR TAX PAYMENT UNDER SECTION 9(5)

It is certain that ECOs would have accumulated the input tax credit on account of the IT development and back-end functions. Apart from discharging its own liability on platform service fee, they may still possess the accumulated input tax credit (esp. in cases where the ECO is burning cash). Therefore, one would wonder whether the input tax credit accumulated through the platform business (say Zomato and Swiggy) would be eligible for utilisation/discharge of output taxes under the Tax-Shift mechanism – in other words whether the tax liability of a restaurant that has been shifted to the ECO by the way of deeming fiction can be discharged through electronic credit ledger balance standing to its account.

As stated above, the deeming fiction of section 9(5) does not merely fix the tax liability on the ECO – it treats the ECO as a supplier for all purposes of the Act. Such deeming fiction must be given a strict interpretation and taken to its logical conclusion. Where the law has fixed the ECO as a supplier for all purposes including the tax obligations, in the absence of a specific bar, the input tax credit otherwise eligible to the ECO on the platform business should, as a natural consequence, devolve upon such ECO.

In this context, the following clarifications of the CBEC6 may also be worth observing:

“2. Would ECOs have to mandatorily take a separate registration w.r.t. supply of restaurant service [notified under 9(5)] through them even though they are registered to pay GST on services on their own account?

As ECOs are already registered in accordance with rule 8 (in Form GST-REG 01) of the CGST Rules, 2017 (as a supplier of their own goods or services), there would be no mandatory requirement of taking separate registration by ECOs for payment of tax on restaurant service under section 9(5) of the CGST Act, 2017

3. Would the ECOs be liable to pay tax on supply of restaurant service made by unregistered business entities?

Yes. ECOs will be liable to pay GST on any restaurant service supplied through them including by an unregistered person.

6. Would ECOs be liable to reverse proportional input tax credit on his input goods and services for the reason that input tax credit is not admissible on ‘restaurant service’?

ECOs provide their own services as an electronic platform and an intermediary for which it would acquire inputs/input service on which ECOs avail Input Tax Credit (ITC). The ECO charges commission/fee etc. for the services it provides. The ITC is utilised by ECO for payment of GST on services provided by ECO on its own account (say, to a restaurant). The situation in this regard remains unchanged even after ECO is made liable to pay tax on restaurant service. ECO would be eligible to ITC as before. Accordingly, it is clarified that ECO shall not be required to reverse ITC on account of restaurant services on which it pays GST in terms of section 9(5) of the Act. It may also be noted that on restaurant service, ECO shall pay the entire GST liability in cash (No ITC could be utilised for payment of GST on restaurant service supplied through ECO)

5. Can the supplies of restaurant service made through ECOs be recorded as inward supply of ECOs (liable to reverse charge) in GSTR-3B? No, ECOs are not the recipient of restaurant service supplied through them. Since these are not input services to ECO, these are not to be reported as inward supply (liable to reverse charge).”

6. 167/23/2021-GST, dated 17-12-2021

Now, the circular makes certain critical points: (a) registration of ECO as a platform service provider and as an ECO can be under one number implying that they need not be distinct persons under law; (b) the tax liability of ECO ought to be discharged necessarily in cash; (c) input tax credit on platform business is permissible to be availed and utilised in terms of section 49 (d) the ECO is not a recipient of services, and hence does not pay tax as RCM. This leads us to the provisions to verify if law bars utilisation of input tax credit to discharge tax payable under section 9(5) as an ECO.

Manner of Payment of Tax: Section 49(4) provides that electronic credit ledger may be used for ‘any payment of output tax’. Rule 86(2) also states that the said ledger could be debited to the extent of ‘any liability’ in terms of section 49, 49A or 49B. Output tax under section 2(82) has been defined in relation to a taxable person, as tax chargeable on taxable supply of goods or services or both made by him or by his agent but excludes tax payable by him on reverse charge basis. Therefore, neither the definition of output tax nor section 49 provide for a separate legal treatment for payments of tax under section 9(5).

Input tax Credit Rationing: Similarly, provisions of section 17(2) r,w,s. 17(3) bar input tax credit only where the ‘recipient’ is liable to pay tax on reverse charge basis. Reverse charge has been defined under section 2(98) as a liability imposed on the ‘recipient’ under section 9(3)/9(4) and does not make any reference to liability imposed under section 9(5). Therefore, the ITC legal provisions do not also place any specific bar on payment of tax liability under section 9(5) through accumulated input tax credit.

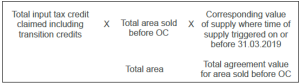

The above analysis could be applied for restaurant services operated through Swiggy/Zomato. The notification prescribing the rates of taxes to restaurant services7 bars the availment of input tax credit used in supplying the restaurant service. Explanation (iv) to the said entry provides that credit used exclusively in supplying the said restaurant services as well as common credits may be reversible on proportionate basis in terms of section 17(2) of the GST law (‘credit rationing provisions’). The fine point which needs to be appreciated is that rate notification conditions as well as provisions of section 17(2) aim at credit rationing at the ‘stage of availment’ and not at the ‘stage of utilisation’. Validly availed input tax credit which have already passed the credit rationing test (such as platform business which is completely taxable) and accruing to the electronic credit ledger, should be available for utilisation of the ‘deemed output tax’ of the ECO under the tax shift mechanism. The difference in availment and utilisation is also evident from the entry for real estate developers which not only bars the availment of ITC, but also bars utilisation (payment) of the output tax liability through input tax credit. The entry for a restaurant does not place any such embargo on input tax credit utilisation.

This issue takes us back to the service tax regime where reverse charge provisions were made applicable to the service recipient as a deemed service provider. Until the amendment in Cenvat regime, input tax credit was permitted to be utilised for payment of tax on reverse charge basis8 since the RCM provisions were treated at par with output tax. Adopting these service tax precedents, one could certainly consider paying taxes under section 9(5) through utilisation of input tax credit despite the Circular’s contrary view.

8. 2012 (25) S.T.R. 129 (P & H) CCE vs. Nahar Industrial Enterprises Ltd; 2014 (33) S.T.R. 148 (Mad.) CCE vs. Cheran Spinners Ltd

TAX COLLECTION MECHANISM

Section 52 provides for collection of tax at source where:

– ECO is not operating as an agent;

– Consideration in respect to supplies are collected by ECO;

Unlike the tax-shift mechanism, the said provisions are purely machinery provisions intended to collect taxes at a convenient point and build a transaction trail. The ECO, being in possession of the funds realised from supply of goods or services, has been tapped by the Government as its tax collecting representative. However, the final tax liability on such supplies would be assessed at the supplier’s end and not at the ECO’s end. Moreover, tax liability, rates, exemptions, etc would also be examined at the supplier’s end and ECO would not have any role to play in tax ascertainment. The said provision also provides that any discrepancy in data populated on the GST system would be communicated to the ECO and the supplier, and tax liability arising therefrom would be recoverable from the supplier. ECO’s liability is extended only to collection of taxes at source and its remittance to the Government.

Whether ECO can discharge the said TCS through input tax credit? The answer is a clear NO. This is because section 52 directs the ECO to collect an ‘amount’ rather than ‘output tax’; whereas section 49 clearly directs ‘amounts’ to be discharged through electronic cash ledger and not through the electronic credit ledger.

AGENCY IN E-COMMERCE

Provisions of section 52 are not applicable if ECO operates as an agent of the supplier. The phrase ‘agent’ has been defined under section 2(5) as being factor, broker, commission agent or any other person who carries the business of another person in representative capacity. Many ECO’s in today’s time perform the following:

– List the products over its platform;

– Promote products through listing preferences;

– Collect orders and transmit the same to the suppliers;

– Collect payments on behalf of the suppliers;

– Manage customer returns through their call centre support;

– Influence the product pricing, etc

The circular9 also emphasises the definition under section 182 of Contract Act to state that a principal agent relationship is present in case the agent has the authority to represent and bind the principal with its actions. Invoicing has been adopted as a critical factor in assessing whether the agent possess representative character in such transactions.

9. No. 57/31/2018 dated 4-9-2018

In many instances, online market place perform clinching actions which make them agents. It is not unknown that marketplaces influence product pricing of suppliers listed on their platform through Flash/ Big Billion-day sales, etc. They also develop systems where invoices are issued by their platform for sales made through them. Payments are also routed through their system and the marketplaces deduct their commissions prior to disbursing the sale proceeds to suppliers. These features make certain ECO’s as agents and hence all GST implications applicable to principal-agent relationships (Schedule-1, etc) would fall upon the ECO. While implications under GST can be addressed and neutralised, the larger concern for such ECO’s emerge on the FDI and Income tax front. The FDI policy may hold them as being engaged in retail trading and hence violating FDI regulations. Income tax would hold that ECOs (especially non-resident in India) as operating in India through agents would be taxable in India. This is a touchy subject and ECOs in the zest for market share sometimes go overboard and expose themselves to tax and regulatory vulnerability.

ONLINE DATABASE AND RETREIVAL SERVICES (OIDAR)

OIDAR was introduced as concept to tax digital services in B2C scenarios under the service tax era and carried forward into the GST regime. Service providers outside India having digital footprint in the country were not subjected to any taxation. B2B OIDAR services were in subjected to RCM taxation in the hands of business recipients under regular provisions.

OIDAR has been defined to apply where services are necessarily mediated through internet or electronic network, and so automated that involves either no or minimal human intervention. The scope of OIDAR services has been further spread-out to include all electronic services such as advertising, cloud services, music/video/textual content, database services, online gaming, etc. The wide expanse of such definition naturally places question on the outer limit of the definition. CBEC circulars10 have clarified that mere order processing or communication of outcomes over internet does not make the services as OIDAR. The essence of OIDAR is that suppliers do not involve any physical exchange with the recipient, and services are delivered entirely over the internet through an automated process – for example pre-recorded video courses were OIDAR but live streaming of the very same course is excluded therefrom.

10. No. 202/12/2016-S.T., dated 9-11-2016

The OIDAR scheme requires the non-resident service provider to assess whether the recipient of their services resides in India through certain parameters (such as address, credit/debit card issuance, IP address, bank account number, SIM country code, etc). By virtue of the digital footprint, the service provider is required to either establish a physical presence or appoint a representative for performing the tax compliances in India.

OTHER ISSUES

In summary, E-commerce has influenced the revenue administration to develop special provisions to address the peculiarities of this sector. Moreover, the sheer volumes and digitisation of the transactions sometimes makes it impossible for one to ascertain the fundamental character of the transactions. ECOs should thus disclaim their responsibilities not just in agreements but also in their acts and insulate from any regulatory risks. ECO startups are adopting innovative marketing techniques to increase their customer base through promotional or incentive programs. Some of them include exclusive co-promotion programs, cash-backs/ incentives, loyalty discounts/points, etc. These issues would be taken up in the subsequent articles.