INTRODUCTION

Since the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India in July 2017, enforcement actions have led to numerous arrests for offenses such as significant tax evasion, fraudulent input tax credit claims, and issuance of fake invoices. Data submitted to the Supreme Court indicates that from July 2017 to March 2024, the number of arrests under the GST framework varied annually, with 3 arrests in 2017-18 and peaking at 460 in 2020-21. In Gujarat alone, central tax officers booked 12,803 GST evasion cases between 2021 and 2024, resulting in 101 arrests. While these enforcement measures aim to deter large-scale fraud, concerns are often raised about potential coercion, especially when recoveries are significantly lower than the detected amounts, highlighting the need for a balanced approach between strict enforcement and maintaining a business-friendly compliance environment. Businesses and impacted individuals are often forced to knock the judicial forums to seek redressal in such situations. In a recent decision (Radhika Agarwal vs. UOI [(2025) 27 Centax 425 (S.C.)]), the Supreme Court has elaborately dealt with the constitutional validity of the provisions concerning power to arrest under the Customs and Goods and Services Tax (GST) law. This article analyses the provisions of arrest under the GST Law and the observations of the Supreme Court in this regard.

CONSTITUTIONAL VALIDITY

The Supreme Court has upheld the constitutional validity of the arrest provisions in Radhika Agarwal on the premise that the parliament, having powers to make laws relating to levy & collection of GST, as a necessary corollary, has powers to enact provisions for tax evasion in the form of powers to summon, arrest and prosecute, which are ancillary and incidental to the power to levy and collect GST.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS RELATING TO ARRESTS

Section 69 of the CGST Act, 2017 deals with the powers to arrest. The relevant provisions are reproduced below:

(1) Where the Commissioner has reasons to believe that a person has committed any offence specified in clause (a) or clause (b) or clause (c) or clause (d) of sub-section (1) of section 132 which is punishable under clause (i) or (ii) of sub-section (1), or sub-section (2) of the said section, he may, by order, authorise any officer of central tax to arrest such person.

A plain reading of the above provisions shows that the provisions of arrest can be invoked only in the following cases:

a) The authorization to arrest must be granted by the Commissioner.

b) There must be reasons to believe that an offense is committed.

c) The offense must be a specified offense for which the powers to arrest can be invoked

REASONS TO BELIEVE

The essential condition for invoking the arrest provisions, as seen above, is that the Commissioner should have reasons to believe that an offense is committed. The phrase “reasons to believe” was recently analyzed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Arvind Kejriwal vs. Directorate of Enforcement [(2025) 2 SCC 248] in the context of PMLA and applied on all fours to customs / GST matters in Radhika Agarwal’s case.

In Arvind Kejriwal’s case, the Hon’ble Supreme Court observes that the powers to arrest without a warrant is a drastic & extreme power. Therefore, the legislature had prescribed safeguards in the language of Section 19 (of PMLA) itself which act as exacting conditions as to how and when the power is exercisable. These safeguards include the requirement to have “material” in the possession of DoE, and based on such “material”, the authorised officer must form an opinion and record in writing their “reasons to believe” that the person arrested was “guilty” of an offence punishable under the PMLA. More importantly, the Supreme Court has held that not only the “grounds of arrest”, but the “reasons to believe” must also be furnished to the arrested persons. In simple words, the “reasons to believe” cannot be some concocted grounds at the whims and fancies of the authorities. It must be based on credible evidence admissible before the Court of law.

The court has held the above principles equally applicable to customs / GST matters. More leverage has been accorded to existence of evidence to form a reason to believe for the simple reason that the Commissioner is not only required to establish whether an offense is committed or not, he also needs to classify the offense as cognizable or non-cognizable. In fact, to do so, there must be a computation or explanation, based on various factors, such as goods seized. Such a level of detail is critical during judicial review of the exercise. This requirement is also laid down by the Board vide Instruction 2/2022-23 dated 17th August, 2022 based on the decision in Siddharth vs. State of UP [(2022) 1 SCC 676] wherein para 3 lays down the specific parameters for its’ Officers:

3.2 Since arrest impinges on the personal liberty of an individual, the power to arrest must be exercised carefully. The arrest should not be made in routine and mechanical manner. Even if all the legal conditions precedent to arrest mentioned in Section 132 of the CGST Act, 2017 are fulfilled, that will not, ipso facto, mean that an arrest must be made. Once the legal ingredients of the offence are made out, the Commissioner or the competent authority must then determine if the answer to any or some of the following questions is in the affirmative:

3.2.1 Whether the person was concerned in the non-bailable offence or credible information has been received, or a reasonable suspicion exists, of his having been so concerned?

3.2.2 Whether arrest is necessary to ensure proper investigation of the offence?

3.2.3 Whether the person, if not restricted, is likely to tamper the course of further investigation or is likely to tamper with evidence or intimidate or influence witnesses?

3.2.4 Whether person is mastermind or key operator effecting proxy / benami transaction in the name of dummy GSTIN or non-existent persons, etc. for passing fraudulent input tax credit etc.?

3.2.5 Unless such person is arrested, his presence before investigating officer cannot be ensured.

3.3 Approval to arrest should be granted only where the intent to evade tax or commit acts leading to availment or utilization of wrongful Input Tax Credit or fraudulent refund of tax or failure to pay amount collected as tax as specified in sub-section (1) of Section 132 of the CGST Act 2017, is evident and element of mens rea / guilty mind is palpable.

3.4 Thus, the relevant factors before deciding to arrest a person, apart from fulfillment of the legal requirements, must be that the need to ensure proper investigation and prevent the possibility of tampering with evidence or intimidating or influencing witnesses exists.

3.5 Arrest should, however, not be resorted to in cases of technical nature i.e. where the demand of tax is based on a difference of opinion regarding interpretation of Law. The prevalent practice of assessment could also be one of the determining factors while ascribing intention to evade tax to the alleged offender. Other factors influencing the decision to arrest could be if the alleged offender is co-operating in the investigation, viz. compliance to summons, furnishing of documents called for, not giving evasive replies, voluntary payment of tax etc.

The Supreme Court in Radhika Agarwal’s case reiterates the above requirements and holds that department’s authority to arrest hinges on satisfying these statutory thresholds (para 44). Infact, it is held that the “reasons to believe” can be subject to judicial review as arrest often involves contestation between the fundamental right to life and liberty of individuals against the public purpose of punishing the guilty. However, it has held that it cannot amount to a review on merits. Such an exercise, in all cases, shall be restricted to the review of material in possession that forms the basis for reasons to believe.

In Dharmendra Agarwal vs. UOI [[2025] 170 taxmann.com 558 (Gauhati)], the non-determination of liability by the respondent authorities before executing the arrest was one of the reasons for the grant of bail. In KshitijGhildiyal vs. DGGI [[2024] 169 taxmann.com 446 (Delhi)], bail was granted since the grounds for arrest were not provided while making the arrest. Post the decision in Kshitij Ghildiyal, the CBIC issued instruction 1/2025-GST dated 13th January, 2025 making it mandatory for the arresting officer to provide the grounds of arrest.

PUNISHABLE OFFENSES

Section 69 requires that the Commissioner must have reasons to believe that an offense is committed. While the statute does not define the term “offense”, section 3(38) of the General Clauses Act, 1897 defines it to mean any act or omission made punishable by any law for the time being in force. Such acts, which amount to an offense are covered u/s 132 of the CGST Act, 2017.

A perusal of the first limb of section 132 (1) brings out an important distinction when compared with section 69. It reads as follows:

(1) [Whoever commits, or causes to commit and retain the benefits arising out of, any of the following offences], namely:—

The distinction is vis-à-vis the applicability of the section. Section 69 applies to an offense committed by a person, while section 132 applies to a person committing, or causing to commit and retain the benefits arising out of the listed offenses. In other words, only a person who commits an offense can be arrested u/s 69 and not the person causing the offense to be committed, i.e., an auxiliary to a crime.

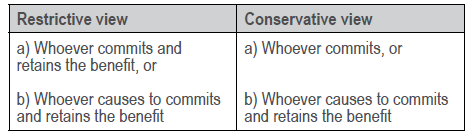

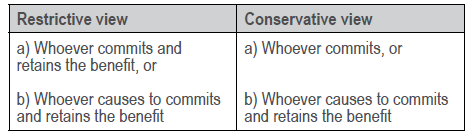

The next question that arises is the interpretation of applicability of section 132(1). The above extracts of section 132(1) can be interpreted in two different ways:

While the first interpretation substantially restricts the applicability of section 132, it may not stand judicial scrutiny. The importance of punctuation marks in interpreting statutes was recently examined by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in ShapoorjiPallonji& Company Private Limited [(2023) 11 Centax 180 (S.C.)] as follows:

27. In the present case, the use of a semicolon is not a trivial matter but a deliberate inclusion with a clear intention to differentiate it from sub-clause (ii). Further, it can be observed upon a plain and literal reading of clause 2(s) that while there is a semicolon after sub-clause (i), sub-clause (ii) closes with a comma. This essentially supports the only possible construction that the use of a comma after sub-clause (ii) relates it with the long line provided after that and, by no stretch of imagination, the application of the long line can be extended to sub-clause (i), the scope of which ends with the semicolon. We are, therefore, of the opinion that the long line of clause 2(s) governs only sub-clause (ii) and not sub-clause (i) because of the simple reason that the introduction of semicolon after sub-clause (i), followed by the word “or”, has established it as an independent category, thereby making it distinct from sub-clause (ii). If the author wanted both these parts to be read together, there is no plausible reason as to why it did not use the word “and” and without the punctuation semicolon. While the Clarification Notification introduced an amended version of clause 2(s), the whole canvas was open for the author to define “governmental authority” whichever way it wished; however, “governmental authority” was re-defined with a purpose to make the clause workable in contra-distinction to the earlier definition. Therefore, we cannot overstep and interpret “or” as “and” so as to allow the alternative outlined in clause 2(s) to vanish.

Therefore, the second interpretation seems more plausible. This takes us to the question of the difference between “commit” & “causes to commit”. The term “commit” refers to the person who has committed the offense while “causes to commit” refers to the person who influences or motivates the person committing the offense. As such, a person who supports / sponsors such offenses though does not commit them, will be equally liable. However, the onus to prove that the offense was caused by such a person will be with the Department. It would also be necessary for the Department to demonstrate that the person causing the offense also retains the benefits derived from the offense so caused.

Section 132 lists the following acts as punishable offenses, providing for arrest and imposition of fines.

- Supplying any goods or services without the issuance of any invoice, with an intention to evade tax [132(1)(a)]

– The phrase is self-explanatory and is intended to cover situations of clandestine removal of goods, under-reporting of services, etc. it may be noted that the situation covered here deals with supply of goods without issuance of invoice and is not intended to cover situations of interpretation relating to classification, valuation, applicability of tax rate or exemption notification, etc.

– Further, for this clause to trigger, the Commissioner must establish “intent to evade tax”. The ‘intention to evade’ assumes some positive act on the part of the alleged person. It is a settled law that the burden to prove the allegation shall be on the accuser, i.e., the Department.

- Issuing any invoice or bill without supply of goods or services or both leading to wrongful availment or utilization of ITC or refund of tax [132(1)(b)]

– This clause refers to a situation where a supplier issues any invoice or bill without the supply of any goods or services, resulting in the wrong availment / utilization of ITC or refund. What is essential for this clause to trigger is that the invoice issued without any underlying supply shall lead to a wrong availment / utilisation of ITC or refund of the tax. If the recipient has not availed / utilized ITC or claimed a refund of such tax, the offense may not arise. Therefore, for the Commissioner to have a reason to believe such an offense is committed, there must exist evidence to that effect. In the absence of such evidence, an allegation under this clause may not survive. It may be noted that intention to evade tax is not a pre-condition for offense under this clause.

- Avails ITC using the invoice or bill referred to above or fraudulently avails ITC without any invoice or bill [132(1)(c)]

– This clause is linked with clause (b). While clause (b) is from the supplier’s perspective, this clause is from the recipient’s perspective and provides that when a person avails ITC on an invoice issued by the supplier without any underlying supply or avails ITC without any invoice or bill.

– Let us first look at an offense where ITC is claimed on the strength of an invoice without any underlying supply being received by the recipient. Generally, such offenses are detected based on the investigation undertaken at the suppliers’ end and notices are sent to all recipients of such supplier based on supplier’s statement. In such cases, based on such a statement, the Department proceeds with a preconceived notion that all supplies made by such suppliers are fake and therefore, the recipients have claimed wrong ITC. It is therefore imperative that in such cases, when the investigation starts, the recipient should make available all the evidence to justify the genuineness of the transactions, such as invoices, payment proofs, delivery challans, EWB, etc., The recipient should also invoke his right to cross-examine all such persons, whose statements are relied upon in such proceedings.

– The next situation covered under this clause is one where ITC is claimed without any invoice / bill. One of the conditions for claiming the ITC u/s 16 is that the recipient should have the tax invoice or prescribed document in his possession, which can be either the original copy or in the forms prescribed u/s 145 of the CGST Act, 2017. However, if any person claims ITC in contravention of this provision, an offense under this clause gets committed. The situation might change if the ITC claimed is already reversed, as the reversal of ITC amounts to non-taking of ITC in the first place, as held in Commissioner vs. Bombay Dyeing & Mfg. Co. Ltd. [2007 (215) E.L.T. 3 (S.C.)]

- Fails to pay the tax collected within three months from the date on which such payment becomes due [132(1)(d)]

– This clause refers to cases where a supplier collects GST but fails to deposit it with the Government. This can be either self-assessed liability (i.e., liability declared in GSTR-1 but not discharged) or liability not disclosed / discharged in return.

- Evades tax / fraudulently obtains refund by committing an offense not covered under (a) to (d) [132(1)(e)]

– This clause refers to a situation of tax evasion / fraudulent refunds (other than cases covered in (a) to (d)). Any instance of non-payment of tax/ fraudulent refund, which is not covered under clauses (a) to (d) may be covered under this clause. However, not all cases of non-payment/ erroneous refunds can be treated as tax evasion / fraudulent. In case of interpretation issues, bona-fide beliefs, etc. where there is no intention to evade / fraud the Government, the said sub-clause may not apply.

- Falsifies or substitutes financial records / produces fake accounts or documents or furnishes false information with an intention to evade tax [132(1)(f)]

– This clause specifically covers cases where a person falsifies / substitutes financial records / produces fake accounts or documents or false information with an intention to evade tax. The documentary evidence to support an allegation that a person has committed this act with an intention to evade tax must exist beforehand.

- Obstructs or prevents any officer in the discharge of his duties under this Act [132(1) (g)] – omitted w.e.f 1st October, 2023

– As a trade-friendly measure, the above offense has been decriminalized w.e.f 1st October, 2023.

- Acquires possession of, or in any way concerns himself in transporting, removing, depositing, keeping, concealing, supplying or purchasing or in any other manner deals with, any goods which he knows or has reasons to believe are liable to confiscation [132(1)(h)]

– This clause refers to cases where goods are liable to be confiscated u/s 130 of the CGST Act, 2017 which is generally triggered in the following cases:

(i) Supply or receipt of any goods in contravention of any of the provisions of this Act or the rules made thereunder with intent to evade payment of tax; or

(ii) Non-accounting of any goods on which he is liable to pay tax under this Act; or

(iii) Supply of goods liable to tax under this Act without having applied for registration; or

(iv) Contravention of any of the provisions of this Act or the rules made thereunder with intent to evade payment of tax; or

(v) Use of any conveyance as a means of transport for carriage of goods in contravention of the provisions of this Act or the rules made thereunder unless the owner of the conveyance proves that it was so used without the knowledge or connivance of the owner himself, his agent, if any, and the person in charge of the conveyance.

– In addition to the above, this clause shall also apply to service providers providing warehousing services if it is found that they are storing goods that are liable to confiscation.

- Receives or is in any way concerned with the supply of, or in any other manner deals with, any services which he knows or has reasons to believe are in contravention of any provisions of this Act or rules made thereunder. [132(1)(i)]

– This clause refers to cases where a person either receives or supplies any service in contravention of any provisions of this Act or rules. An example of contravention would be when a person, though liable to register under GST, does not register and continues to supply service. Such a supply would be in contravention of the provisions of section 22.

- Tampers with or destroys any material evidence or documents [132(1)(j)] – omitted w.e.f 1st October, 2023

– As a trade-friendly measure, the above offense has been decriminalized w.e.f 1st October, 2023

- Failure to supply any information which he is required to supply under this Act or the rules made thereunder or (unless with a reasonable belief, the burden of proving which shall be upon him, that the information supplied by him is true) supplies false information [132 (1)(k)]– omitted w.e.f 1st October, 2023

– As a trade-friendly measure, the above offense has been decriminalized w.e.f 1st October, 2023

- Attempts to commit, or abet the commission of any of the offenses mentioned above [[132 (1)(l)].

– This clause covers cases where a person aids or abets in the commission of any offense specified in section 132. In one of the cases, a tax practitioner was arrested alleging he had facilitated registration based on fake & vague documents for evading GST, thus abetting the commission of an offense. (Satya Prakash Singh vs. State of Jharkhand [2025] 170 taxmann.com 684 (Jharkhand)].

A perusal of section 132 makes it clear that all cases of non-payment of tax / short-payment of tax/ wrong availment or utilization of ITC do not trigger the arrest provisions. Only when an offense specified under specific clauses and exceeding specified monetary limit is committed can a person be arrested. Therefore, genuine cases involving interpretation issues, such as rate classification, valuation, exemption eligibility, ITC eligibility, etc. cannot be covered under the offenses prescribed u/s 132 & in such cases, arrest provisions cannot be invoked. This shows that cases involving interpretation issues are given more flexibility and such cases cannot be treated as a punishable offense. This has also been clarified by instruction 2/2022-23-GST dated 17th August, 2022.

PUNISHMENTS

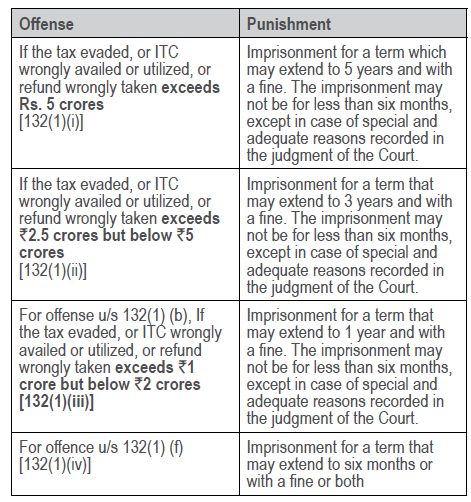

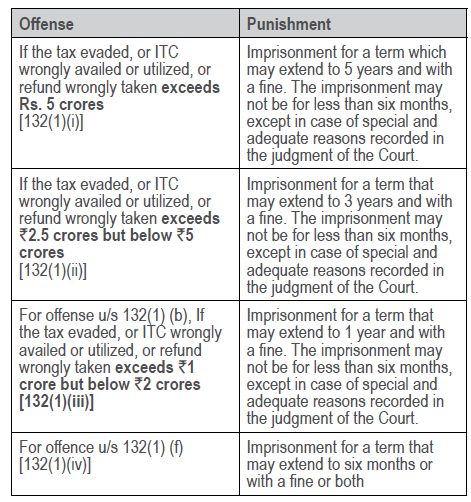

The punishment for the above offenses, based on the tax quantum involved, is prescribed u/s 132(1), as follows:

Section 132(2) further provides that a repeat offender shall be liable to imprisonment for a term that may extend up to 5 years with a fine for each subsequent offense. However, no person shall be prosecuted without the previous sanction of the Commissioner [section 132 (6)].

It is interesting to note that the punishment is prescribed only for offenses specified in clauses (b), (c), (e), and (f). Before 1st October, 2023, sub clause (iii) referred to any other offense, which has been now substituted with an offense under clause (b). Therefore, while the prescribed acts are offenses, no punishment is prescribed for them. Therefore, to that extent, even if the person commits the said acts, he cannot be punished, since no such punishment is prescribed under the law. In this regard, one may refer to Vijay Singh vs. State of UP [2012 (5) SCC 242]:

16. Undoubtedly, in a civilized society governed by rule of law, the punishment not prescribed under the statutory rules cannot be imposed. Principle enshrined in Criminal Jurisprudence to this effect is prescribed in legal maxim nullapoena sine lege which means that a person should not be made to suffer penalty except for a clear breach of existing law. In S. Khushboo v. Kanniammal&Anr., AIR 2010 SC 3196, this Court has held that a person cannot be tried for an alleged offence unless the Legislature has made it punishable by law and it falls within the offence as defined under Sections 40, 41 and 42 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, Section 2(n) of Code of Criminal Procedure 1973, or Section 3(38) of the General Clauses Act, 1897. The same analogy can be drawn in the instant case though the matter is not criminal in nature.

OFFENSES – COGNIZABLE & NON-COGNIZABLE

In general, all the offenses are declared as non-cognizable &bailable offenses [section 132 (4)] except for the offenses covered under clause (a) to (d) which are punishable under (i) above [section 132(5)].

The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 classifies an offense as either “cognizable” or “non-cognizable”. The distinction between cognizable and non-cognizable offenses is in the manner of arrest. An arrest for a cognizable offense can be made without an arrest, i.e., a person can be arrested without a warrant. In contrast, the arrest in case of a non-cognizable offense can be made only based on an arrest warrant. The classification of an offense into cognizable & non-cognizable depends on the gravity of the offense and is provided u/s 132.

SPECIFIED OFFENSES – WHERE A PERSON CAN BE ARRESTED U/S 69

The third limb of section 69, to invoke the arrest provisions, is that the Commissioner should have reasons to believe that a specified offense is committed. While section 132 provides a list of acts as offenses, the arrest provisions can be invoked only in case of specified offenses, as follows:

a) An offense under clauses (a) to (d) of section 132(1) should have been committed.

b) The offense must be punishable under sub-clause (i) section 132, i.e., the tax amount involved exceeds ₹5 crores, making the offense cognizable & non-bailable.

c) The offense must be punishable under sub-clause (i) section 132, i.e., the tax amount involved exceeds ₹2.50 crores but is less than ₹5 crores, making the offense non-cognizable &bailable.

In other words, the powers to arrest by the Commissioner can be exercised in cases of specified cognizable & non-cognizable offenses. However, when a person is authorized for a non-cognizable and therefore, a bailable offense based on the authorization issued by the Commissioner, such person arrested shall be admitted in bail, or in the default of bail, forwarded to the custody of the Magistrate until such time that a bail is furnished.

EXECUTING THE ARREST

Section 4(2) of the IPC, 1860 provides that the offenses covered under laws other than IPC, 1860 shall be investigated, inquired, tried, or otherwise dealt with under the CrPC, 1973 (“code”). Section 5 carves out a savings clause to clarify that the Code shall not affect any special / local law, or any special jurisdiction or powers conferred or special procedure prescribed unless there is a specific provision prescribed. In other words, the provisions of the Code would apply to the extent that there is no contrary provision in the special act or any special provision excluding the jurisdiction and applicability of the Code. In the context of GST, in Radhika Agarwal, it has been held that the provisions of the Code shall equally apply to customs’ offense and by extension, to GST as well.

As stated above, section 69 provides for cases where the Commissioner may authorize any officer of central tax to arrest a person. However, for other offenses, the GST law is silent. Hence, in such cases, the procedure prescribed under the Code shall apply. This takes us to the Code. Chapter V thereof deals with the arrest of persons. A perusal of Chapter V provides for arrest by a police officer. The question that arises is whether the GST officer is a police officer. This issue has been examined by Courts on multiple occasions1 and recently summarised in Radhika Agarwal wherein it has been held that GST officers are not police officers.

1 State of Punjab vs. Barkat Ram, (1962) 3 SCR 338, Ramesh Chandra Mehta vs.

State of West Bengal,

(1969) 2 SCR 461, Illias v. Collector of Customs (1969) 2 SCR 613,

Tofan Singh vs. State of Tamil Nadu [(2s021) 4 SCC 1]

Therefore, while in cases covered u/s 69, the GST officers can execute the arrest, for all other offenses, the arrest can be executed only by a police officer. In such cases, the arrest can be executed by a police officer based on a complaint filed by the GST Officer (section 41 (b) of the code). However, as provided in section 132 (6), no person shall be prosecuted without the prior sanction of the Commissioner. Therefore, even for prosecution in other offenses, a prior sanction of the Commissioner is mandatory.

Once a person is arrested, either u/s 69 by a GST officer or a police officer, the arrested person shall be presented before a Magistrate within 24 hours of the arrest, excluding the traveling time between the place of arrest & the Magistrate’s Court. Even in case of arrests u/s 69, it is incumbent upon the arresting officer to admit the arrested person to bail, or in default of bail, forward it to the custody of the magistrate.

When a person is presented before the Magistrates’ Court, the Magistrate shall, if the investigation is not completed within 24 hours of the arrest and feels that further investigation is required, order that such arrested person must remain in police custody for not more than 15 days. However, in case of GST offenses, custody may be granted to the GST officers, as held in Directorate of Enforcement vs. Deepak Mahajan [(1994) 3 SCC 440].

A person arrested for offenses u/s 132 shall have all the rights, whether arrested u/s 69 by a GST officer / by a police office under Chapter V of the Code, such as:

a) The right to meet an advocate of his choice during the investigation, but not throughout the investigation and have such advocate present within a visual distance but not audible distance during the investigation (section 41D of the code).

b) The right to give information regarding such arrest and place where the arrested person is being held to any of his friends, relatives, or other person as may be disclosed or nominated by the arrested person (section 50A of the code)

c) The guidelines laid down in D K Basu vs. State of West Bengal [(1997) 1 SCC 416] must be stringently followed.

Similarly, the duties and obligations cast on a police officer under the Code shall equally apply to the GST officers. This includes the obligation to maintain a diary of investigation proceedings, taking reasonable care of the arrested persons’ health and safety, etc.,

Double jeopardy – can a person be subjected to simultaneous proceedings u/s 73/74 as well as section 69?

As stated above, there can be instances where proceedings u/s 73 or 74 have already been initiated. The question that arises is whether in such cases, proceedings u/s 69 alleging offenses u/s 132 can be initiated. In other words, can there be simultaneous civil & criminal proceedings for the same offense or not?

This issue has been dealt with in the case of Maqbool Hussain vs. State of Bombay [1983 (13) E.L.T. 1284 (S.C.)] wherein the Constitutional Bench held that sea customs authorities are not judicial tribunals. Therefore, proceedings by sea customs authorities do not constitute prosecution and the Orders passed by them did not constitute punishment. Therefore, separate criminal proceedings can be initiated against the accused for such offense and the same would not be hit by double jeopardy. This view was also followed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Leo Roy Frey vs. Superintendent [1983 (13) E.L.T. 1302 (S.C.)] and RadheshyamKejriwal [[2011 (266) ELT 294 (SC)]]. One may also refer to instruction 4/2022-23 dated 1st September, 2022 which deals with this aspect of parallel criminal & adjudication proceedings.

In fact, relying on Makemytrip (India) Private Limited vs. UOI [2016 SCC OnLine Del 4951], one of the arguments raised in Radhika Agarwal was that prosecution can be done only after adjudication proceedings are completed. However, this argument has been rejected and it has been held that there could be cases where even without a formal order of assessment, the department / Revenue is certain that it is a case of offense under clauses (a) to (d) to sub-section (1) of Section 132 and the amount of tax evaded, etc. falls within clause (i) of sub-section (1) to Section 132 of the GST Acts with sufficient degree of certainty. In such cases, the Commissioner may authorise arrest when he is able to ascertain and record reasons to believe. This reiterates that there is no relationship between the adjudication proceedings or prosecution for offenses.

PRE-ARREST PROTECTION

Any person apprehending prosecution and arrest has a right to apply for anticipatory bail. In Radhika Agarwal’s case, it has been held as follows:

70. We also wish to clarify that the power to grant anticipatory bail arises when there is apprehension of arrest. This power, vested in the courts under the Code, affirms the right to life and liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution to protect persons from being arrested. Thus, in Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia (supra), this Court had held that when a person complains of apprehension of arrest and approaches for an order of protection, such application when based upon facts which are not vague or general allegations, should be considered by the court to evaluate the threat of apprehension and its gravity or seriousness. In appropriate cases, application for anticipatory bail can be allowed, which may also be conditional. It is not essential that the application for anticipatory bail should be moved only after an FIR is filed, as long as facts are clear and there is a reasonable basis for apprehending arrest. This principle was confirmed recently by a Constitution Bench of Five Judges of this Court in Sushila Aggarwal and others v. State (NCT of Delhi) and Another (2020) 5 SCC 1. Some decisions State of Gujarat v. ChoodamaniParmeshwaranIyer and Another, 2023 SCC OnLine SC 1043; Bharat Bhushan v. Director General of GST Intelligence, Nagpur Zonal Unit Through Its Investigating officer, SLP (Crl.) No. 8525/2024 of this Court in the context of GST Acts which are contrary to the aforesaid ratio should not be treated as binding.

POST-ARREST STEPS

Once a person is arrested, pending trial, he shall remain in custody unless granted bail. Chapter XXXIII of the Code deals with provisions relating to bail.

Section 436 of the code provides that a person arrested for a bailable offense shall be released on bail. Similarly, for non-bailable offenses, section 437 of the code provides that the bail may be granted subject to the exceptions provided therein (such as cases where the punishment for the alleged offense is death or life imprisonment, or a repeat offender). However, in any case, when a person undergoes detention for more than one-half of the maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offense, he shall be released by the Court on his bond with or without sureties (section 436A of the code).

In addition, there is a settled principle of law that bail is the norm, jail is an exception, which has been upheld for economic offenses (see Prem Prakash vs. UOI).

There are many reported cases where bail has been granted for non-bailable offenses also:

- In Ashutosh Garg vs. UOI [[2024] 164 taxmann.com 767 (SC)], the bail has been granted upon having served a substantial time in detention, pending trial.

- In yet another case2, the bail was granted since the co-accused was granted bail.

- In DGGI vs. Harsh Vinodbhai Patel [Director General of Goods and Service Tax Intelligence, Ahmedabad vs. Harsh Vinodbhai Patel [2024] 164 taxmann.com 410 (SC)], bail was granted since all documentary evidences and other material were seized by the investigation agency, the presence of accused was not necessary for the investigation and trial was unlikely to commence and conclude in near future. Similar view was followed in the case of Ratnambar Kaushik vs. UOI [[2022] 145 taxmann.com 296 (SC)].

- In Natwar Kumar Jalan vs. UOI [[2025] 171 taxmann.com 112 (Gauhati)], one of the reasons for a grant of bail was that the accused was not a flight risk.

2 Ronaldo Earnest Ignatio vs. State of Odisha [[2024] 167 taxmann.com 418 (Orissa)]

CONCLUSIONS

The Supreme Court, while upholding the legislative competence of the Parliament to incorporate criminal provisions under GST law, has delivered a balanced judgment reinforcing constitutional safeguards to protect personal liberty. The decision in Radhika Agarwal also imposes a glaring requirement on the tax officers to invoke the arrest provisions only based on substantial evidence, which can be subjected to judicial review and reiterates the rights of the arrested persons, by following the guidelines laid down in D K Basu, Deepak Mahajan, etc, This shows that Courts shall, as they always have, continue to maintain the balance between the curtailment of tax evasion and the liberty of the individual. On the other hand, taxpayers will have to be equivalently vigilant with their tax practices, i.e., filing of returns, responding to department notices and submissions before the department, and so on, and in case of impending prosecution and / or arrests, proactively take preventive steps.

Every year, the most awaited event is the budget. What the Finance Minister unfolded on 29th February 2016 with respect to the direct tax provisions was covered in the Public Lecture Meeting held on 4th March 2016 by Senior Advocate Mr. S. E. Dastur. This was the 51st Budget Lecture Meeting of the Society and 28th year of address by Mr. S. E. Dastur. This year the Society has captured pre budget expectations and post budget inteviews from the stalwarts and the youth. Just before the lecture began, a series of views of various people on the budget were taken by Mr. Ameet Patel. All these videos are available on our website as well as Youtube channel and also on social media.

Every year, the most awaited event is the budget. What the Finance Minister unfolded on 29th February 2016 with respect to the direct tax provisions was covered in the Public Lecture Meeting held on 4th March 2016 by Senior Advocate Mr. S. E. Dastur. This was the 51st Budget Lecture Meeting of the Society and 28th year of address by Mr. S. E. Dastur. This year the Society has captured pre budget expectations and post budget inteviews from the stalwarts and the youth. Just before the lecture began, a series of views of various people on the budget were taken by Mr. Ameet Patel. All these videos are available on our website as well as Youtube channel and also on social media. President Raman Jokhakar welcomed the speaker, Senior Advocate Mr. Vikram Nankani, an eminent speaker on the subject to throw light on the amendments of the changes by the Finance bill 2016.The lecture meeting commenced with the launch of the new publication of the Society “Partnership Firms – Registration Procedure and Frequently Faced Issues with Registrar of Firms” by Mr. Uday Sathaye, Past President of the Society. The book was launched by the speaker Mr. Nankani.

President Raman Jokhakar welcomed the speaker, Senior Advocate Mr. Vikram Nankani, an eminent speaker on the subject to throw light on the amendments of the changes by the Finance bill 2016.The lecture meeting commenced with the launch of the new publication of the Society “Partnership Firms – Registration Procedure and Frequently Faced Issues with Registrar of Firms” by Mr. Uday Sathaye, Past President of the Society. The book was launched by the speaker Mr. Nankani.  Professionals like CA’s, Advocates, Businessmen are finding it difficult to Register Partnership Firms with Registrar of Firms in Maharashtra due to various issues. This process of registration involves submission of documents and the careful adherence to a procedure which has been laid down.

Professionals like CA’s, Advocates, Businessmen are finding it difficult to Register Partnership Firms with Registrar of Firms in Maharashtra due to various issues. This process of registration involves submission of documents and the careful adherence to a procedure which has been laid down.

His address was followed by the interactive session wherein the panel of RBI officers provided views on the written queries provided to them in advance. The queries covered all important areas of FEMA including those dealing with ODI, FDI, LRS, ECB and Trade transactions. The Officers answered the queries and also dealt with several questions from the audience.

His address was followed by the interactive session wherein the panel of RBI officers provided views on the written queries provided to them in advance. The queries covered all important areas of FEMA including those dealing with ODI, FDI, LRS, ECB and Trade transactions. The Officers answered the queries and also dealt with several questions from the audience. The post lunch technical sessions was on “Trade Transactions” by Mr. Shabbir Motorwala who succinctly covered the vast subject in the time available with him. The last session was on “ECBs” wherein Mr. Kumar Saurabh Singh covered the recent amendments in the ECB policy and also dealt with the other financing routes available to borrowers. Both the speakers answered queries from the audience and covered the subjects in significant detail. The Conference was received well by all present.

The post lunch technical sessions was on “Trade Transactions” by Mr. Shabbir Motorwala who succinctly covered the vast subject in the time available with him. The last session was on “ECBs” wherein Mr. Kumar Saurabh Singh covered the recent amendments in the ECB policy and also dealt with the other financing routes available to borrowers. Both the speakers answered queries from the audience and covered the subjects in significant detail. The Conference was received well by all present.  It was once again a proud moment for BCAS and BCAS Foundation to organise a music concert “Udat Abeel Gulal”, together with a few other organisations at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan on 19th March, 2016 in aid of Dilasa Sanstha, an NGO engaged in relief work for drought affected farmers of Maharashtra. Attended by a large audience, it started with jugalbandi of Santoor and Saraswati Veena by Shri Snehal Muzoomdar, Maithili Muzoomdar on Santoor and Shri Narayan Mani on Saraswati Veena respectively, accompanied by a team of virtuoso musicians and interspersed with Vedic chants by Ved Pandit Dr. Narasimha Ghanpatigal. Explaining the theme “Bairagi se Basant”, Compere Mihir Sheth vividly created background atmosphere for celebration of spring with quotes from Kalidasa and Rig-Veda. Narrating the ethos of the theme and quoting medieval poet Maagh, he said when season of Basant arrives, its enchanting beauty feels us with a sense of bliss, Abeel and Gulal colour our lives, the fire of Holi protects our lives, give us the prosperity and hence, we all invoke Firegod Agni as narrated in Agnisooktam in Rig-Veda whose hymns are often chanted in raga Bairagi.

It was once again a proud moment for BCAS and BCAS Foundation to organise a music concert “Udat Abeel Gulal”, together with a few other organisations at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan on 19th March, 2016 in aid of Dilasa Sanstha, an NGO engaged in relief work for drought affected farmers of Maharashtra. Attended by a large audience, it started with jugalbandi of Santoor and Saraswati Veena by Shri Snehal Muzoomdar, Maithili Muzoomdar on Santoor and Shri Narayan Mani on Saraswati Veena respectively, accompanied by a team of virtuoso musicians and interspersed with Vedic chants by Ved Pandit Dr. Narasimha Ghanpatigal. Explaining the theme “Bairagi se Basant”, Compere Mihir Sheth vividly created background atmosphere for celebration of spring with quotes from Kalidasa and Rig-Veda. Narrating the ethos of the theme and quoting medieval poet Maagh, he said when season of Basant arrives, its enchanting beauty feels us with a sense of bliss, Abeel and Gulal colour our lives, the fire of Holi protects our lives, give us the prosperity and hence, we all invoke Firegod Agni as narrated in Agnisooktam in Rig-Veda whose hymns are often chanted in raga Bairagi.  The Jugalbandi started with raga Bairagi rendered on Santoor and Saraswati Veena interspersed with chanting of Vedic hymns and then deftly moved on to raga Basant and Kafi, which are the popular ragas of the Basant season, accompanied by vocalists Shraddha Shridharni in Hindustani style and Nupur Joshi in Carnatic style. Both the vocalists recreated magic with their rendition of poet Nanhalal’s poems so ably composed by Snehal Muzoomdar. Fine balance of melodious music with perfect percussion and dramatic entry of vocalists on the stage left the audience completely mesmerised when it reached the crescendo in the end.

The Jugalbandi started with raga Bairagi rendered on Santoor and Saraswati Veena interspersed with chanting of Vedic hymns and then deftly moved on to raga Basant and Kafi, which are the popular ragas of the Basant season, accompanied by vocalists Shraddha Shridharni in Hindustani style and Nupur Joshi in Carnatic style. Both the vocalists recreated magic with their rendition of poet Nanhalal’s poems so ably composed by Snehal Muzoomdar. Fine balance of melodious music with perfect percussion and dramatic entry of vocalists on the stage left the audience completely mesmerised when it reached the crescendo in the end.  The Human Development & Technology Initiative Committee continued with the annual CSR activity of supporting Eye Camp for the tribals and the needy people from the rural area surrounding Vansda, Dist. Navsari.

The Human Development & Technology Initiative Committee continued with the annual CSR activity of supporting Eye Camp for the tribals and the needy people from the rural area surrounding Vansda, Dist. Navsari.  The Committee had set a target of one Eye Camp with a Budget of Rs.51,000/- for cataract surgery of 51 patients. However, with divine grace and kind support of all donor friends, it was able to collect Rs.2,17,200, which can take care of 217 patients i.e. little over four Eye Camps.

The Committee had set a target of one Eye Camp with a Budget of Rs.51,000/- for cataract surgery of 51 patients. However, with divine grace and kind support of all donor friends, it was able to collect Rs.2,17,200, which can take care of 217 patients i.e. little over four Eye Camps.