By Mayur B. Nayak | Tarunkumar G. Singhal | Anil D. Doshi | Mahesh G. Nayak

Chartered Accountants

In the first of this two-part article published in June, 2021, we analysed some of the issues relating to the Equalisation Levy on E-commerce Supply and Services (‘EL ESS’) – what is meant by online sale of goods and online provision of services; who is considered as an E-commerce Operator (‘EOP’); and what is the amount on which the Equalisation Levy (‘EL’) is leviable.

In this part, we attempt to address some other issues relating to EL ESS such as those relating to the situs of the recipient, turnover threshold and specified circumstances under which EL ESS shall apply. We also seek to understand the interplay of the EL ESS provisions with tax treaties, provisions relating to Significant Economic Presence (‘SEP’), royalties / Fees for Technical Services (‘FTS’) and the exemption u/s 10(50) of the ITA.

1. ISSUES RELATING TO RESIDENCE AND SITUS OF CONSUMER

Section 165A(1) of the Finance Act, 2016 as amended (‘FA 2016’) states that the provisions of EL ESS apply on consideration received or receivable by an EOP from E-commerce Supply or Services (‘ESS’) made or provided or facilitated by it:

a) To a person resident in India; or

b) To a non-resident in specified circumstances; or

c) To a person who buys such goods or services or both using an internet protocol (‘IP’) address located in India.

The specified circumstances under which the ESS made or provided or facilitated by an EOP to a non-resident would be covered under the EL ESS provisions are:

a) Sale of advertisement, which targets a customer who is resident in India, or a customer who accesses the advertisement through an IP address located in India; and

b) Sale of data collected from a person who is resident in India or from a person who uses an IP address located in India.

Therefore, the EL ESS provisions apply to a non-resident EOP if the consumer, to whom goods are sold or services either provided to or facilitated, is a person resident in India, or one who is using an IP address located in India.

Interestingly, the words used in the EL provisions are different from those used in the provisions relating to SEP and the extended source rule in Explanations 2A and 3A to section 9(1)(i) of the ITA, respectively. The EL ESS provisions refer to the recipient of the ESS being a ‘person resident in India’, whereas the SEP provisions in Explanation 2A refer to the recipient of the transaction being a ‘person in India’. Similarly, the extended source rule in Explanation 3A refers to certain transactions with a person ‘who resides in India’.

While the terms ‘person in India’ and person ‘who resides in India’ referred to in Explanations 2A and 3A, respectively, refer to the physical location of the recipient in India, the term ‘person resident in India’ used in the EL provisions would refer to the tax residency of a person. While the EL ESS provisions do not define the term ‘resident’, one would interpret the same on the basis of the provisions of the ITA, specifically section 6.

This may lead to some challenging situations which have been discussed below.

Let us take the example of an EOP who is selling goods online. While such an EOP may have the means to track its customers whose IP address is located in India, how would it be able to keep track of customers who are residents in India but whose IP address is not located in India? This would be typically so in a case where a person resident in India goes abroad and purchases some goods through the EOP. Further, it would also be highlighted that unlike citizenship, the residential status of an individual is based on specific facts and, therefore, may vary from year to year and one may not be able to conclude with surety, before the end of the said previous year, whether or not one is a resident of India. A similar issue would also arise in the case of a company, especially a foreign company having its ‘Place of Effective Management’ in India and, therefore, a tax resident of India.

Similarly, let us take the example of a foreign branch of an Indian company purchasing some goods from a non-resident EOP. In this case, as the branch is not a separate person but merely an extension of the Indian company outside India, the provisions of EL ESS could possibly apply as the goods are sold by the EOP to ‘a person resident in India’.

While one may argue that nexus based on the tax residence of the payer is not a new concept and is prevalent even in section 9 of the ITA, for example in the case of payment of royalty or fees for technical services (‘FTS’), the main challenges in applying the payer’s tax residence-based nexus principle to EL are as follows:

a) While the payments of royalty and FTS may also apply for B2C transactions, the primary application is for B2B transactions. On the other hand, the EL provisions may primarily apply to B2C transactions. Therefore, the number of transactions to which the EL provisions apply would be significantly higher;

b) In the case of payment of royalty and FTS, the primary onus is on the payer to deduct tax at source u/s 195, whereas the primary onus in the case of EL ESS is on the recipient. The payer would be aware of its tax residence in the case of payment of royalty and FTS and, hence, would be able to determine the nexus, whereas in the case of EL the recipient may not be in a position to determine the tax residential status of the payer.

Given the intention of the provisions to bring to the tax net, income from transactions which have a nexus with India and applying the principle of impossibility for the non-resident EOP to evaluate the residential status of the customer, one of the possible views is that one may need to interpret the term ‘person resident in India’ to mean a person physically located in India rather than a person who is a tax resident of India.

However, in the view of the authors, from a technical standpoint a better view may be that one needs to consider the tax residency of the customer even though it may seem impossible to implement in practice on account of the following reasons:

a) Section 165A(1) of the FA 2016 has three limbs – a person resident in India, a non-resident in specified circumstances, and a person who uses an IP address in India. The reference in the second limb to a non-resident as against a person who is not residing in India indicates the intention of the law to consider tax residency.

b) The third limb of section 165A(1) of the FA 2016 refers to a person who uses an IP address in India. If the intention was to cover a person who is physically residing in India under the first limb, this limb would become redundant as a person who uses an IP address in India would mean a person who is physically residing in India at that time. This also indicates the intention of the Legislature to consider a person who is a tax resident rather than a person who is merely physically residing in India under the first limb.

c) Section 165 of the FA 2016 dealing with Equalisation Levy on Online Advertisement Services (‘EL OAS’) applies to online advertisement services provided to a person resident in India and to a non-resident person having a PE in India. Given that the section refers to a PE of a non-resident, it would mean that tax residence rather than physical residence is important to determine the applicability of the EL OAS provisions. In such a case, it may not be possible to apply two different meanings to the same term under two sections of the same Act.

2. SALE OF ADVERTISEMENT

As highlighted above, one of the specified circumstances under which ESS made or provided or facilitated by an EOP to a non-resident would be covered under the EL ESS provisions, is of sale of advertisement which targets a customer who is resident in India, or a customer who accesses the advertisement through an IP address located in India.

The question which arises is in respect of the possible overlap of the EL ESS and the EL OAS provisions. In this respect, section 165A(2)(ii) of the FA 2016 provides that the provisions of EL ESS shall not apply if the EL OAS provisions apply. In other words, the EL OAS application shall override the application of the EL ESS provisions.

EL OAS provisions apply in respect of payment of online advertisement services rendered by a non-resident to a resident or to a non-resident having a PE in India. However, the application of EL ESS provisions is wider. For example, the EL ESS provisions can also apply in the case of payment for online advertisement services rendered by a non-resident to another non-resident (which does not have a PE in India), which targets a customer who is a resident in India or a customer who accesses the advertisement through an IP address located in India.

3. ISSUES IN RESPECT OF TURNOVER THRESHOLD

Section 165A(2)(iii) of the FA 2016 provides that the provisions of EL shall not be applicable where the sales, turnover or gross receipts, as the case may be, of the EOP from the ESS made or provided or facilitated is less than INR 2 crores during the previous year. Some of the issues in respect of this turnover threshold have been discussed in the ensuing paragraphs.

3.1 Meaning of sales, turnover or gross receipts from the ESS

The first question which arises is what is meant by ‘sales, turnover or gross receipts’. The term has not been defined in the FA 2016 nor in the ITA. However, given that the term is an accounting term, one may be able to draw inference from the Guidance Note on Tax Audit u/s 44AB issued by the ICAI (‘GN on tax audit’). The GN on tax audit interprets ‘turnover’ to mean the aggregate amount for which the sales are effected or services rendered by an enterprise. Similarly, ‘gross receipts’ has been interpreted to mean all receipts whether in cash or kind arising from the carrying on of business.

The question which needs to be addressed is this – in the case of an EOP facilitating the online sale of goods, what should be considered as the turnover? To understand this issue better, let us take an example of goods worth INR 100 owned by a third-party seller sold on the portal owned by an EOP whose commission or fees for facilitating such sales is INR 5. Let us assume further that the buyer pays the entire consideration of INR 100 to the EOP and the EOP transfers INR 95 to the seller after reducing the facilitation fees.

In such a case, what would be considered as the turnover for the purpose of determining the threshold for application of EL ESS? As the EL provisions provide that the consideration received or receivable from the ESS shall include the consideration for the value of the goods sold irrespective of whether or not the goods are owned by the EOP, can one argue that the same principle should apply in the case of the computation of turnover as well, i.e., turnover in the above case is INR 100?

In the view of the authors, considering the facilitation fee earned by the EOP as the turnover of the EOP may be a better view, especially in a scenario where the EOP is merely facilitating the sale of goods and is not undertaking the risk associated with a sale. One may draw inference from paragraph 5.12 of the GN on tax audit which, following the principles laid down in the CBDT Circular No. 452 dated 17th March 1986, provides as below:

‘A question may also arise as to whether the sales by a commission agent or by a person on consignment basis forms part of the turnover of the commission agent and / or consignee, as the case may be. In such cases, it will be necessary to find out whether the property in the goods or all significant risks, reward of ownership of goods belongs to the commission agent or the consignee immediately before the transfer by him to third person. If the property in the goods or all significant risks and rewards of ownership of goods belong to the principal, the relevant sale price shall not form part of the sales / turnover of the commission agent and / or the consignee, as the case may be. If, however, the property in the goods, significant risks and reward of ownership belongs to the commission agent and / or the consignee, as the case may be, the sale price received / receivable by him shall form part of his sales / turnover.’

Moreover, section 165A(2)(iii) of the FA 2016 also refers to sales, turnover or gross receipts of the EOP.

Therefore, in the view of the authors, in the above example the turnover of the EOP would be INR 5 and not INR 100.

3.2 Whether global turnover to be considered

Having evaluated the meaning of the term ‘turnover’, a question arises as to whether the global turnover of the EOP is to be considered or only that in relation to India is to be considered. Section 165A(2)(iii) of the FA 2016 provides that the turnover threshold of the EOP is to be considered in respect of ESS made or provided or facilitated as referred to in sub-section (1). Further, section 165A(1) of the FA 2016 refers to ESS made or provided or facilitated by an EOP to the following:

(i) to a person resident in India; or

(ii) to a non-resident in the specified circumstances; or

(iii) to a person who buys such goods or services or both using an IP address located in India.

Accordingly, the section is clear that the turnover in respect of transactions with a person resident in India or an IP address located in India is to be considered and not the global turnover.

3.3 Issues relating to application of threshold of INR 2 crores

Another question is whether the turnover threshold of INR 2 crores applies to each person referred to in section 165A(1) independently or should one aggregate the turnover for all the persons who are covered under the sub-section.

This issue is explained by way of an example. Let us assume that an EOP sells goods to the following persons during the F.Y. 2021-22:

|

Person

|

Value of goods sold

(in lakhs INR)

|

Applicable clause of

section 165A(1)

|

|

Mr. A, a person resident in India

|

50

|

(i)

|

|

Mr. B, a person resident in India

|

125

|

(i)

|

|

Mr. C, a non-resident under specified circumstances

|

100

|

(ii)

|

|

Mr. D, a non-resident but using an IP address located in India

|

25

|

(iii)

|

|

Total

|

300

|

|

In the above example, the issues are as follows:

a) As each clause of section 165A(1) refers to ‘a person’, whether such threshold is to be considered qua each person. In the above example, the transactions with each person do not exceed INR 2 crores.

b) As each clause of section 165A(1) is separated by ‘or’, does the threshold need to be applied qua each clause, i.e., in the above example the transactions with persons under each individual clause do not exceed INR 2 crores.

In other words, the question is whether one should aggregate the turnover in respect of sales to all the persons which are covered u/s 165A(1). In the view of the authors, while a technical view that the turnover threshold of INR 2 crores applies to each buyer independently and not in aggregate is possible, the better view may be that the turnover threshold applies in respect of all transactions undertaken by the EOP in aggregate.

Interestingly, the Pillar One solution as agreed amongst the majority of the members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, provides for a global turnover of the entity of EUR 20 billion.

4. INTERPLAY BETWEEN PE AND EL ESS

One of the exemptions from the application of the EL ESS is in a scenario where the EOP has a PE in India and the ESS is effectively connected to such PE. The term ‘permanent establishment’ has been defined in section 164(g) of the FA 2016 to include a fixed place through which business is carried out, similar to the language provided in section 92F(iii) of the ITA. The question arises whether the definition of PE under the FA 2016 would include only a fixed place PE or whether it would also include other types of PE such as service PE, dependent agent PE, construction PE, etc.

In this regard, one may refer to the Supreme Court decision in the case of DIT (International Taxation) vs. Morgan Stanley & Co. Inc.1 wherein the Apex Court held that the definition of PE under the ITA is an inclusive definition and, therefore, would include other types of PE as envisaged in tax treaties as well.

However, in the view of the authors, ‘Service PE’ may not be considered under this definition under the domestic tax law as the duration of service period for constitution of Service PE is different under various treaties and the definition under a domestic tax law cannot be interpreted on the basis of the term given to it under a particular treaty when another treaty may have a different condition. A similar view may also be considered for construction PE where under different tax treaties the threshold for constitution of PE also is different.

5. INTERPLAY BETWEEN EL ESS AND ROYALTY / FEES FOR TECHNICAL SERVICES

Section 163 of the FA 2016 provides that the EL ESS provisions shall not apply if the consideration is taxable as royalty or FTS under the ITA as well as the relevant tax treaty. Similarly, section 10(50) of the ITA also exempts income from ESS if such income has been subject to EL and is otherwise not taxable as royalty or FTS under the ITA as well as the relevant tax treaty.

Accordingly, one would need to apply the royalty / FTS provisions first and the EL ESS provisions would apply only if the income were not taxable as royalty / FTS under the ITA as well as the tax treaty.

Interestingly, when the EL provisions were introduced, the exemption u/s 10(50) of the ITA applied to all income and this carve-out for royalty / FTS did not exist. This amendment of taxation of royalty / FTS overriding the EL provisions was introduced by the Finance Act, 2021 with retrospective effect from F.Y. 2020-21.

Prior to the amendment as mentioned above, one could take a view that transactions which, before the introduction of the EL provisions, were taxable under the ITA at a higher rate, would be subject to EL ESS at a lower rate.

In order to understand this issue better, let us take an example of IT-related services provided by a non-resident online to a resident. Such services may be considered as FTS u/s 9(1)(vii) of the ITA as well as under the tax treaty (assuming the make available clause does not exist). Prior to the amendment made vide Finance Act, 2021, one could take a view that such services may be subject to EL (assuming that the service provider satisfies the definition of an EOP) and therefore result in a lower rate of tax in India at the rate of 2% as against the rate of 10% as is available in most tax treaties. However, with the amendment vide the Finance Act, 2021, one would need to apply the royalty / FTS provisions under the ITA and tax treaty first and only if such income is not taxable, can one apply the EL ESS provisions. Therefore, now such income would be taxed at the FTS rate of 10%.

An interesting aspect in the royalty vs. EL debate is in respect of software. Recently, the Supreme Court in the case of Engineering Analysis Centre of Excellence (P) Ltd. vs. CIT (2021) (432 ITR 471) held that payment towards use of software does not constitute royalty as it is not towards the use of the copyright in the software itself. In fact, the Court reiterated its own view as in the case of Tata Consultancy Services vs. the State of AP (2005) (1 SCC 308) that the sale of software on floppy disks or CDs is sale of goods, being a copyrighted article, and not sale of copyright itself.

It is important to highlight that the facts in the case of Engineering Analysis (Supra) and the way business is at present undertaken are different as software is no longer sold on a physical medium such as floppy disks or CDs but is now downloaded by the user from the website of the seller. A question arises whether one can apply the principles laid down by the above judgment to the present business model.

In the view of the authors, downloading the software is merely a mode of delivery and does not impact the principle emanating from the Supreme Court judgment. The principle laid down by the judgment can still be applied to the present business model wherein the software is downloaded by the user as there is no transfer of copyright or right in the software from the seller to the user-buyer.

Accordingly, payment by the user to the seller for downloading the software may not be considered as royalty under the ITA or the relevant tax treaty.

The next question which arises is whether such download of software can be subject to EL ESS.

Assuming that the portal from which the download is undertaken is owned or managed by the seller, the first issue which needs to be addressed is whether sale of software by way of download would be considered as ESS.

Section 164(cb) of the FA 2016 defines ESS to mean online sale of goods or online provision of services or online facilitation of either or a combination of activities mentioned above.

While the Supreme Court has held that the sale of software would be considered as sale of copyrighted material, the ‘goods’ being referred to by the Court are the floppy disk or CD – the medium through which the sale was made. In the view of the authors, the software itself may not be considered as goods.

Further, such download of software may not be considered as provision of services as well.

One may take inference from the SEP provisions introduced in Explanation 2A of section 9(1)(i) of the ITA, wherein SEP has been defined to mean the following,

‘(a) transaction in respect of any goods, services or property carried out by a non-resident with any person in India including provision of download of data or software in India…’

In this case, one may be able to argue that if the download of software was considered as sale of goods or services, there was no need for the Legislature to specifically include the download of data or software in the definition and a specific mention was required to be made, is on account of the fact that download of software does not otherwise fall under transaction in respect of goods, services or property.

Accordingly, it may be possible to argue that download of software does not fall under the definition of ESS and the provisions of EL, therefore, cannot apply to the same. However, this issue is not free from litigation.

In this regard, it is important to highlight that in a scenario where the transaction is in the nature of Software as a Service (‘SaaS’), it may not be possible to take a view that there is no provision of service and such a transaction may, therefore, either be taxed as FTS or under the EL ESS provisions, as the case may be, and depending on the facts.

6. INTERPLAY BETWEEN EL AND SEP PROVISIONS

Section 10(50) of the ITA exempts income arising from ESS provided the same is not taxable under the ITA and the relevant tax treaty as royalty or FTS and chargeable to EL ESS. Therefore, while the provisions of SEP under Explanation 2A of section 9(1)(i) of the ITA may get triggered if the threshold is exceeded, such income would be exempt if the provisions of EL apply.

In other words, the provisions of EL supersede the provisions of SEP.

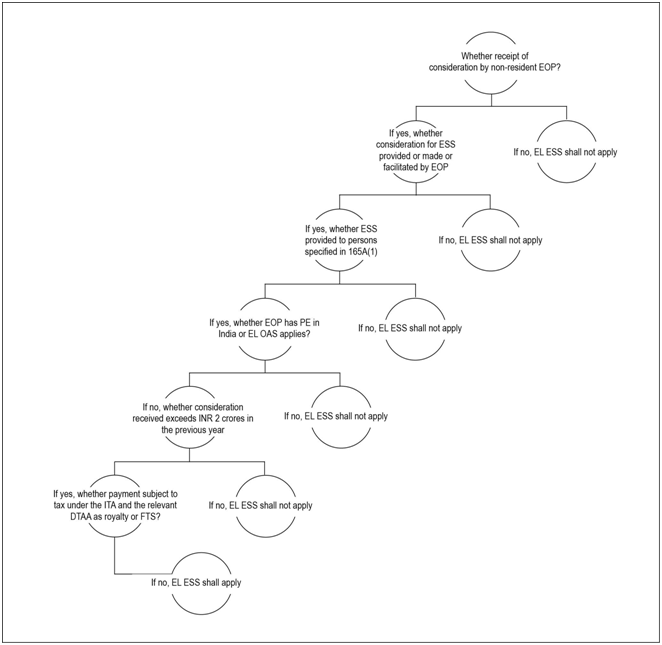

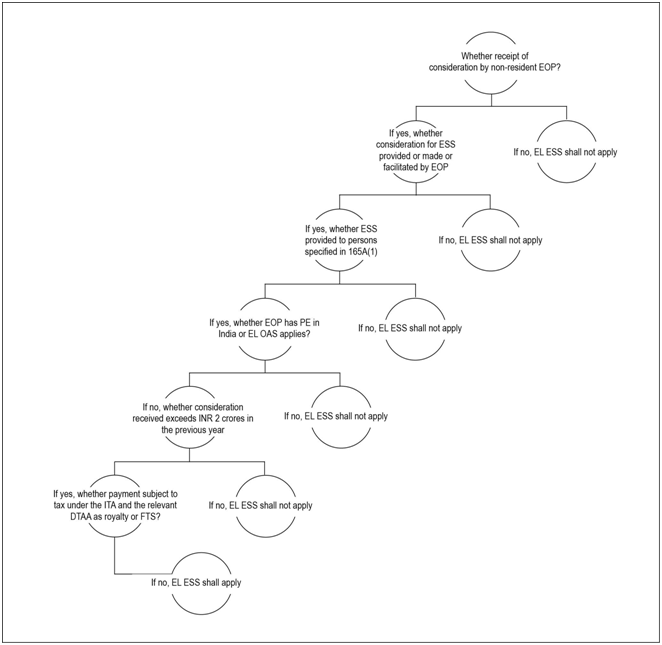

7. ORDER OF APPLICATION OF EL ESS

A brief chart summarising the order of application of EL ESS has been provided below:

8. WHETHER EL IS RESTRICTED BY TAX TREATIES

One of the fundamental questions which arises in the case of EL is whether such EL is restricted by the application of a tax treaty. The Committee on Taxation of E-commerce, constituted by the Ministry of Finance which recommended the enactment of EL in 2016, in its report stated that EL which is enacted under an Act other than the ITA, would not be considered as a tax on ‘income’ and is a levy on the services and, therefore, would not be subject to the provisions of the tax treaties which deal with taxes on income and capital.

However, due to the following reasons, one may be able to take a view that EL may be a tax on ‘income’ and may be restricted by the application of the tax treaties:

a. The speech of the Finance Minister while introducing EL in the Budget 2016, states, ‘151. In order to tap tax on income accruing to foreign e-commerce companies from India, it is proposed that …..’;

b. While EL is enacted in the FA 2016 itself and not as part of the ITA, section 164(j) of the FA 2016 allows the import of definitions under the ITA into the relevant sections of the FA 2016 dealing with EL in situations where a particular term is not defined under the FA 2016. Further, the FA 2016 also includes terms such as ‘previous year’ which is found only in the ITA;

c. In order to avoid double taxation, section 10(50) of the ITA exempts income which has been subject to EL. Now, if EL is not considered as a tax on ‘income’, where is the question of double taxation in India;

d. While under a separate Act the assessment for EL would be undertaken by the Income-tax A.O. Further, similar to income tax, appeals would be handled by the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) and the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal, as the case may be;

e. The Committee, while recommending the adoption of EL, stated that such an adoption should be an interim measure until a consensus is reached in respect of a modified nexus to tax such transactions. Therefore, it is clear that the EL is merely a temporary measure until India is able to tax the transactions and EL would take the colour of a tax on ‘income’.

This view is further strengthened in a case where Article 2 of a tax treaty covers taxes which are identical or substantially similar to income tax. Most of the tax treaties which India has entered into have the clause which covers substantially similar taxes. In such a scenario, one may be able to argue that even if one considers EL as not an income tax, it is a tax which is similar to income tax on account of the reasons listed above and therefore would get the same tax treatment.

Further, one may consider applying the principles of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) to determine whether EL would be restricted under a tax treaty. Article 31(1) of the VCLT provides that:

‘A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in light of its object and purpose.’

The object of a tax treaty is to allocate taxing rights between the contracting states and thereby eliminate double taxation. In case EL is held as not covered under the ambit of the tax treaty, it would defeat the object and purpose of the tax treaty and lead to double taxation. In this regard, it may be important to highlight that while India is not a signatory to the VCLT, VCLT merely codifies international trade practice and law.

However, courts would also take into account the intention of the Legislature while adopting EL. EL has been adopted in order to override the tax treaties as such treaties were not able to adequately capture taxing rights in certain transactions.

9. CONCLUSION

On 1st July, 2021, more than 130 countries out of the 139 members of the OECD / G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS released a statement advocating the two-pillar solution to combat taxation of the digitalised economy and unfair tax competition. While the details are yet to be finalised, it is expected that the implementation of Pillar One would result in the withdrawal of the unilateral measures enacted, such as the EL. However, given the high threshold agreed for application of Pillar One, it is expected that less than 100 companies would be impacted by the reallocation of the taxing right sought to be addressed in the solution. Therefore, whether such unilateral measures would be fully withdrawn or only partially withdrawn to the extent covered by Pillar One, is still not clear. Further, the multilateral agreement proposed under Pillar One would be open for signature only in the year 2022 and is expected to be implemented only from the year 2023. Accordingly, EL provisions would continue to be applicable, at least for the next few years.