In the Indian context, Tax authorities often challenge the benefits under a Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (“DTAA” or “tax treaty”) to fiscally transparent entities (“FTEs”) such as foreign partnership firms, trusts, foundations, limited liability company (“LLC”) etc. on the premise that such entities do not qualify as a tax ‘resident’ of that country and are not ‘liable to tax’ in their home country. Whether an FTE can access the tax treaty has been a contentious issue. In this Article, we are analysing some recent judicial developments in this context.

INTRODUCTION

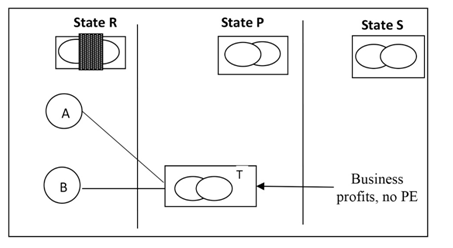

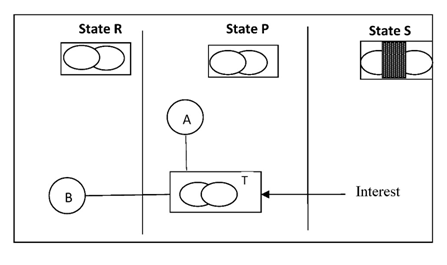

In order to mitigate double taxation in case of cross-border transaction(s), countries have entered into DTAA or tax treaty, which allocates the taxing rights among the Treaty Countries. One of the main conditions that need to be satisfied to access a tax treaty is that the taxpayer should be a tax ‘resident’ (i.e. taxable unit) of either or both the Treaty Countries and is ‘liable to tax’ therein. An exception to this in certain cases is where it appears that the condition of ‘liable to tax’ is subsumed in determining if the taxpayer is resident and once he is resident, whether liable or not does not matter. For example under the India – UAE DTAA, a person is ‘resident’ of UAE if he stays for 183 days in the calendar year concerned and no relevance is provided to being ‘liable to tax’. For illustrative purposes, in this Article, we have considered the provisions of the India-US DTAA.

Article 1 – Personal Scope (in case of India-US DTAA ‘General Scope’) of a Tax Treaty typically provides that ‘This convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States.’

Article 3(1)(e) defines the term ‘person’ as follows – “the term “person” includes an individual, an estate, a trust, a partnership, a company, any other body of persons, or other taxable entity.’

Article 4 – Resident (in case of India-US DTAA ‘Residence’) typically provides that for the purposes of a convention, the definition of the term “resident of a Contracting State”.

Article 4(1) of the India-US DTAA reads as follows:

“For the purposes of this convention, the term “resident of a Contracting State” means any person, who under the laws of that State, is liable to tax therein by reason of his domicile, residence, citizenship, place of management, place of incorporation, or any other criterion of a similar nature, provided, however, that:

(a) This term does not include any person who is liable to tax in that State in respect only of income from the sources in that State; and

(b) In the case of income derived or paid by a partnership, estate, or trust, this term applies only to the extent that the income derived by such partnership, estate, or trust is subject to tax in that State as income of a resident, either in its hands or in the hands of its partners or beneficiaries.”

FTEs such as partnerships, LLCs and trusts are popular across the world considering the legal requirements for certain professions (such as law firms) as well as the ease of doing business without having to undertake significant compliances (as is required to be undertaken in a corporate structure). For tax purposes, these FTEs allow income to ‘pass through’ them i.e. income is taxed at the level of their partners / members / beneficiaries and there is no taxation at the entity level. Given the pass-through status for tax purposes, this has raised the contentious issue as to whether such entities can claim benefits under tax treaties. Tax authorities contend that such entities do not fall under the definition of ‘person’ under tax treaties and that they are not a ‘resident’ in its state of incorporation / location as they are not ‘liable to tax’ in that country and that it is the partners / members / beneficiaries who are taxed in that country.

In the context of Partnerships, certain countries (like Singapore, China, Netherlands etc.) consider partnerships as FTE whereas some countries (like India, Mexico, Hungary etc.) consider partnership as a taxable unit.

Over the years, jurisprudence has developed on whether FTEs can claim benefits under Indian tax treaties. The SC in Azadi Bachao Andolan case ((2003) 263 ITR 706 SC) laid down the principle that liability to taxation is a legal situation and payment of tax is a fiscal fact. Essentially, the SC held that actual payment of tax is not necessarily needed in order to be ‘liable to tax’. In context of partnerships, the ITAT in case of Linklaters LLP ((2010) 40 SOT 51 Mum) held that considering that one of the fundamental objectives of tax treaties is to provide relief to economic double taxation, even when a partnership firm is taxable in respect of its profits, not in its own hands but in the hands of the partners, as long as the entire income of the partnership firm is taxed in the residence country, treaty benefits cannot be denied.

In context of trusts, the Authority for Advance Ruling (AAR), in case of General Electric Pension Trust ([2005] 280 ITR 425), denied tax treaty benefit to the foreign trust considering that the trust was not subject to tax on account of an exemption under the US tax law.

Thus, while judicial precedents exist on the eligibility of tax transparent partnerships being eligible to avail DTAA, similar guidance on the applicability of similar principle to an LLC, was hitherto not available.

Eligibility of a LLC incorporated in USA to claim benefit under India-US DTAA

The Delhi ITAT’s decision in the case of General Motors Company USA vs. ACIT, IT [2024] 166 taxmann.com 170 (Delhi-Trib.), is the first case where the ITAT has upheld the ability of an LLC to claim treaty benefit under the India-US DTAA.

In this case, the taxpayer, an LLC incorporated in Delaware, US, was classified as a disregarded entity; that is, not regarded to be separate from its owner for US tax purposes. For AY 2014-15 and 2015-16, the taxpayer earned income in the nature of ‘Fees for Included Services’. The taxpayer offered this income to tax in India at the rate of 15% under Article 12 of the India-US DTAA instead of 25% (i.e. the tax rate under section 115A of the Income-tax Act, 1961 (“the Act”) during the relevant assessment years). A tax residency certificate (“TRC”) issued by the US tax authorities was furnished by the taxpayer along with the Form 10F to meet the requirements for availing the benefits under India-US DTAA. The Assessing Officer (“AO”) passed an order denying the India-US DTAA benefits to the taxpayer on the ground that it was an FTE and not subject to tax in the US. Accordingly, the AO levied a tax rate of 25% under section 115A of the Act.

The Dispute Resolution Panel upheld the AO’s order, after which the matter went to Delhi bench of the ITAT.

TAX DEPARTMENT’S VIEW

The Revenue contended that based on the taxpayer’s own claim, the taxpayer is an FTE under US tax laws and accordingly, its income is not subject to tax in its own hands in the US.

The Revenue denied the India-US DTAA benefits to the taxpayer for two reasons. The First reason the Revenue contended is that such LLCs do not qualify as ‘Resident’ for the purpose of Article 4 of the India-US DTAA. Only persons who are ‘liable to tax’ in their country according to the laws of that country can be considered to be a ‘resident’ for the purpose of the India-US DTAA. In the instant case, since the income earned by the taxpayer is not liable to tax in the US in their own hands, as per the arguments put forth by the Revenue, it does not qualify as a person ‘resident’ in the US according to the Article 4 of the India-US DTAA.

Secondly, LLCs are not covered under the ambit of the special clause in Article 4(1)(b) of the India-US DTAA, which provides guidance on tax residency related to tax transparent entities such as partnerships, estates and trusts.

The Revenue also relied on paragraph 8.4 of Article 4 of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) commentary on Model Convention, which states that where a country disregards a partnership for tax purposes and treats it to be fiscally transparent, and taxes the partners on their share of the partnership income, the partnership itself is not ‘liable to tax’. Therefore, it may not be considered to be a resident of that country.

Accordingly, it was argued that the income earned by the taxpayer should be subjected to tax at 25% under the Act.

ASSESSEE’S CONTENTION

a) The taxpayer contended that under the US domestic tax law, an LLC has an option to either be taxed as a corporation or be considered as a disregarded entity wherein the LLC’s income is clubbed in the hands of its owner who discharges the tax that is assessable in the hands of the LLC in the US. Hence, while the LLC itself is not paying tax, its tax liability is discharged by its owners in the US.

b) The taxpayer contended that the term ‘liable to tax’ has not been defined under the India-US DTAA, and thus, referred to –

i. OECD Commentary 2017 on Article 4, which states that a person is considered to be liable to comprehensive taxation even if the country does not impose a tax.

ii. The commentary of Professor Philip Baker, which states that a person does not have to be actually paying the tax to be liable to tax.

It contended that being ‘liable to tax’ connotes that a person is subject to tax in a country, and whether the person actually pays the tax or not is immaterial.

c) Reliance was also placed on various judicial authorities:

i. UoI vs. Azadi Bachao Andolan [2003] 253 ITR 706 (SC) wherein it noted that for the purposes of the application of Article 4 of a DTAA, the legal situation is relevant—i.e. the liability to taxation—and not the fiscal fact of payment of tax.

ii.Linklaters LLP vs. ITO (ITAT-Mum) [2010] 40 SOT 51 wherein it concluded that while the modalities of taxation may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, what really matters is that income is taxed in the residence jurisdiction. With reference to a fiscally transparent UK partnership firm, it was held that as long as its entire income is taxed in the residence country, the DTAA benefits cannot be denied.

iii. TD Securities (USA) LLC vs. Her Majesty the Queen 12 ITLR 783 of the Tax Court of Canada, Toronto, wherein it was held that an LLC incorporated in Delaware, US, and classified a disregarded entity to be considered as resident of US for the DTAA purpose.

d) Regarding the second aspect raised by the Revenue that Article 4(1)(b) of the India-US DTAA provides specific guidance on the residency of tax transparent entities which covers partnerships, estates and trusts, but does not cover LLCs, the taxpayer made following arguments:

i. the India-US DTAA (executed in 1989) is based on the 1981 US model convention when

the US laws did not recognise single member LLCs as a disregarded entity for the purpose of tax. The concept of disregarded LLCs was introduced into the US tax laws only in 1996. Hence, disregarded LLCs were not envisaged at the time of entering into the India-US DTAA.

ii. The technical explanation to the US Model Convention issued by US Internal Revenue Services (IRS) has explained that this provision prevents fiscally transparent entities from claiming the DTAA benefits where the owner of such an entity is not subject to tax on the income in its state of residence.

This suggests that, ordinarily, a fiscally transparent entity will be eligible to be treated as a resident who is eligible to claim the benefit under India-US DTAA.

iii. Based on the above guidance from the IRS, it was contended that an ambulatory approach must be adopted while interpreting the India-US DTAA; that is, the meaning of the term prevailing under the US tax laws at the time of applying the India-US DTAA should be adopted and not that at the time when the India-US DTAA was signed. Hence, a disregarded US LLC should be held to be eligible to claim the benefit under India-US DTAA.

e) Basis the above, as the taxpayer is a US tax resident, it should be eligible to claim the benefits under the India-US DTAA.

ITAT DELHI RULING

The ITAT Delhi while deciding the appeal in favour of the taxpayer i.e. permitting the US LLC to access the India-US DTAA and thereby granting the beneficial DTAA rate, inter alia, relied on IRS Publications and Instructions and made below mentioned observations.

US IRS PUBLICATION AND INSTRUCTIONS:

Publication 3402 on Taxation of LLCs, of the US IRS explains that an LLC is a business entity organized in the United States under state law and may be classified for US federal income tax purposes as a partnership, corporation, or an entity disregarded as separate from its owner by applying the rules in Regulations section 301.7701-3.

Default classification: An LLC with at least two members is classified as a partnership for federal income tax purposes and an LLC with only one member is treated as an entity that is disregarded as separate from its owner for income-tax purposes.

An LLC can elect to be classified as an association taxable as corporation or as an S corporation.

If an LLC has only one member and is classified as an entity disregarded as separate from its owner, its income, deductions, gains, losses, and credits are reported on the owner’s income tax return.

Instruction for Form 8802 (Application for US Residency Certification in Form 6166) issued by US IRS provides that in general, under an income tax treaty, an individual or entity is a resident of the US if the individual or entity is subject to US tax by reason of residence, citizenship, place of incorporation, or other similar criteria. US residents are subject to tax in the US on their worldwide income. It further provides that in general, an FTE organized in the US (that is, a domestic partnership, domestic grantor trust, or domestic LLC disregarded as an entity separate from its owner) and which does not have any US partners, beneficiaries, or owners then such an entity is not eligible for US residency certification in Form 6166.

The Instruction for Form 8802 also provides that the Form 6166 having residency certification is in the form of a letter of US residence certification only certify that, for the certification year (the period for which certification is requested), the applicant were resident of US for purposes of US taxation or, in the case of a FTE, that the entity, when required, filed an information return and its partners/ members/owners/beneficiaries filed income tax returns as resident of United States.

VALIDITY OF TRC

The ITAT held that the TRC as received from the US IRS in accordance with the requirement of the law as applicable to the assessee, being an LLC, which is organised as body corporate as it fulfills all the requirements of a body corporate in the form of legal recognition of a separate existence of the entity from its Member and a perpetual existence distinct from its Members. Thus, the assessee being a resident under Article 4 of the India-US Tax Treaty by virtue of incorporation and its recognition as a separate existence from its Members qualifies as a ‘person’.

LIABLE TO TAX

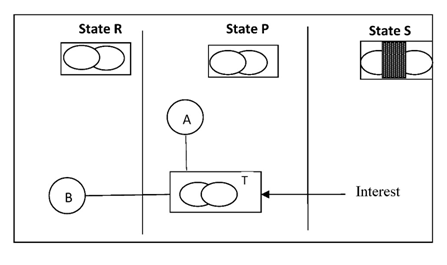

The ITAT held that the taxpayer is liable to tax in the resident State by virtue of US Income-tax Law as an LLC is given an option to either be taxed as a corporation or be taxed as a disregarded entity or partnership (depending on number of members) wherein the income of the LLC is clubbed in the hands of its owner who merely discharges the tax that is assessable in the case of the LLC.

The ability of the LLC to elect its classification as well as where the LLC is disregarded as separate from its tax owner and the payment of tax is by the owner(s) of the LLC, supports the legal situation of an LLC being ‘liable to tax’.

The ITAT further held that the phrase ‘liable to tax’ has to be interpreted in the way that the assessee is liable to tax under the authority of the US Income-tax law. The intent of the Indo-US Treaty has to be given precedence wherein the concept of a FTE is recognized for recognizing the phrase ‘liable to tax’.

Accepting the reliance on the decision of the ITAT Mumbai in case of Linklaters LLP vs. ITO [2010] 40 SOT 51, wherein in case of a UK-based limited liability partnership firm which was treated as a FTE in the UK, it was held that while the modalities or mechanism of taxation may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, what really matters is whether the income, in respect of which treaty protection is being sought, is taxed in the treaty partner country or not and thus held that even when a partnership firm is taxable in respect of its profits not in its own right but in the hands of the partners, as long as the entire income of the partnership firm is taxed in the residence country, treaty benefits cannot be declined.

The ITAT also held that Article 4(1)(b) imposes a limitation on eligibility of a partnership to avail the benefits of India-US tax treaty as prescribed, i.e., it seeks to exclude from the eligibility of provisions of India-US tax treaty such income of the partnership which is not ‘subject to tax’ in the US (either in the hands of partnership or partners). Relying on the AAR ruling in case of General Electric Pension Trust (supra) it observed that in this consideration of the matter, it can be concluded that an exclusion provision can only exclude something if it was included at the outset. Hence, a fiscally transparent partnership was already regarded as ‘liable to tax’ for the purposes of India-US tax treaty and this provision determines the scope of eligibility of such fiscally transparent partnership by excluding income which is not ultimately ‘subject to tax’ in the US.

THE OTHER VIEW

In this connection, it is very pertinent to note the recent decision of the Irish Court of Appeal – Civil, dated 27th May, 2025 in the case of Susquehanna International Securities Ltd. & Others vs. The Revenue Commissioners [2025] 175 taxmann.com 1054 (CA – UK) (“the Susquehanna case”). In this case, with respect to Ireland-US DTAA, in the context of entitlement to group relief under section 411 of the Irish Taxes Consolidation Act, 1997 (“TCA”), on the specific and somewhat unusual / peculiar facts of the taxpayer’s group structure, the court concluded that the Taxpayers’ parent company Susquehanna International Holdings LLC (“SIH LLC”), by reason of its fiscal transparency, was not ‘liable to tax’ in the US and accordingly was not resident in the US within the meaning of Article 4 of the Double Taxation Treaty and that the Taxpayers were not entitled to group relief under section 411 of the TCA.

The Court of Appeal ultimately held that SIH LLC was not itself ‘liable to tax’ in the US and consequently, did not meet the definition of “resident of a contracting state” under Article 4.1. In this regard Justice Allen noted that “If – as it is – the purpose of the treaty is to avoid double taxation, it seems to me that it stands to reason that it should only apply to persons who otherwise would be exposed to a liability to pay tax. SIH LLC had no such exposure.”

On the basis that SIH LLC did not satisfy the definition of “resident of a contracting state”, the Court of Appeal held that SIH LLC was not entitled to rely on the anti-discrimination provisions contained in Article 25 of the DTAA.

TD Securities Case: While arriving its conclusion, the court considered the decision of the Tax court of Canada in the case of TD Securities (USA) LLC (supra) in the context of Canada US DTAA and distinguished the same on the basis that the LLC in TD Securities was ultimately held by a corporation which was subject to US tax (as opposed to SIH LLC which was held by other disregarded entities and ultimately US individuals). The Court of Appeal was of the view that TD Securities was based on US and Canadian interpretation of the US-Canada double tax treaty and consequently, its findings were not persuasive in an Irish court.

In para 87 of the decision, the Irish Court of Appeal also referred to the ITAT Delhi’s decision in the case of General Motors Company, USA vs. ACIT (supra) but the Judge did not dwell on it.

The Susquehanna Case is the first Irish case to consider the tax residence of a US LLC. The case confirmed that a disregarded US LLC ultimately owned by individuals who are liable to tax in the US on the income of the LLC should not be regarded as a resident of the US for the purposes of the DTAA. It appears the Susquehanna Case ultimately turned on the specific and somewhat unusual facts of the taxpayer’s group structure.

It remains to be seen whether an Irish court would reach a different conclusion if a US disregarded LLC was held by a corporation who is subject to US tax.

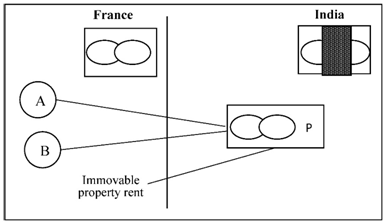

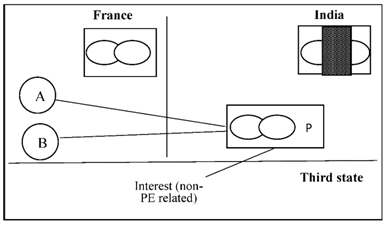

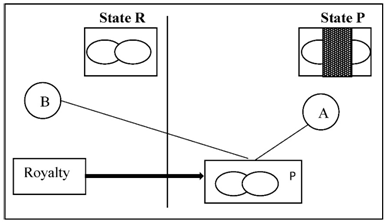

Applicability to other pass-through entities from other jurisdictions

While the General Motors (supra) ruling has focused on the US treatment of LLCs, the question arises is whether one can apply the principle set in the said decision along with other decisions such as Linklaters (supra), etc could apply to other pass-through entities based out of jurisdictions wherein the treaty with India is silent about treatment of partnerships or other pass-through entities. The key difference is that DTAAs such as India – US or India – UK specifically provide treatment for partnerships in Article 3 (dealing with definition of person) and Article 4 (dealing with residence). In the past, the courts have upheld the entitlement to treaty benefits to pass-through entities from other jurisdictions such as Germany as well. Further, it is important to once again point out that the Delhi ITAT in the case of General Motors (supra) held that the reference to partnership in the India – US DTAA is not to provide benefit to partnerships but is to limit the allowability of benefit to partnerships in cases where all the partners are not residents of that jurisdiction. Further, this ruling also follows the general principle of interpretation of treaty that one should not misuse the benefit of a treaty but at the same time if one is paying tax in that jurisdiction either directly or through partners, members or other entities, then one should be able to claim the benefit of the treaties entered into by that jurisdiction. Therefore, in the view of the authors, one may be able to argue that treaty benefits are available to the extent that the partners / members are tax residents of that jurisdiction.

CONCLUSION

Whether an FTE can access a tax treaty has been a contentious issue and in the Indian context the General Motor Company’s ruling strengthen / support the contention that the tax treaty benefit should not be denied to an FTE especially when its owners / partners / shareholders are from the same country.

While this ruling lays down a precedent on this issue, the same has been challenged before the high court and the final position would depend upon the outcome at the higher appellate level. However, it is also important to obtain appropriate documentation in addition to the TRC to substantiate the share of profit of the partners/members who are residents of the same jurisdiction as the FTE.

From the above discussion, a view can it be taken that the treaty benefit should be given to the “pass through entity”, where all partners / members are residents of the treaty partner country or if some of the partners / members are residents of the treaty partner country, to the extent of partners/members who are resident of the treaty partner country.