estate is undoubtedly one of the most complex sectors, be it from the

perspective of levy of tax, quantification of tax or the claim of input

tax credit. This is perhaps because there are different facets involved,

as a transaction of sale of constructed unit is not a simple

transaction of sale of goods or services but is a complex transaction

involving transfer of land / share in land, transfer of goods in the

execution of contract and the provision of services of construction.

From the perspective of indirect taxes, a contract for sale of unit, be

it residential / commercial, is a works contract also involving the

transfer of land / share in land.It is for this reason that

under legacy laws, i.e., VAT and service tax, a lower tax rate was

prescribed. For instance, in VAT, in Maharashtra, the sector had an

option to pay tax at a standard rate of 1 per cent of agreement value

while service tax was levied on 1/4th of the agreement value or 1/3rd of

the agreement value. While the rate prescribed under VAT law was a

composition scheme, meaning no corresponding input tax credit for the

dealers, under service tax, the taxpayer was eligible to claim CENVAT

credit, though only on input services, i.e., credit of tax paid on

capital goods and inputs was not available. This restriction on claim of

input tax credit was through a conditional notification, which provided

for an abatement in the value of taxable services resulting in an

effectively lower rate vide notification 26/2012-ST dated 20th June,

2012 as amended from time to time.On the other hand, under GST,

there was no upfront restriction on claim of input tax credit initially

as works contract was deemed to be a supply of service and the builder

was entitled to claim full input tax credit of tax paid on goods and

services received in the course or furtherance of business. However,

notification 11/2017-CT (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 which prescribes

the rate of tax for services provided that in case of supply of service

involving transfer of land or undivided share of land, the value of

supply shall be 2/3rd of the total amount charged for such supply.Subsequently,

w.e.f 01st April, 2019, the tax regime for the real estate sector

underwent substantial changes. The projects were classified into two

categories, namely:

a) Residential Real Estate Project: A

project in which carpet area of commercial apartments is not more than

15 per cent of total carpet area of all apartments in the REP. The

effective tax rate applicable on outward supply was reduced to 1 per

cent / 5 per cent with a condition of no corresponding input tax credit.

b)

Other than RREP: A project other than Residential Real Estate Project,

wherein the total carpet area of commercial apartments was more than 15

per cent of total carpet area of all apartments. While the tax rate on

residential apartments was reduced to 1 per cent / 5 per cent with no

corresponding input tax credit, the commercial apartments continued to

be taxable at 12 per cent with eligible input tax credit.

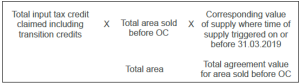

However,

for ongoing projects, the taxpayer had an option to continue pay tax

under the existing rates or pay tax under the new scheme. In case of

ongoing projects where the option to pay tax under the new tax rate was

applied, the developer was also required to reverse the input tax credit

attributable to construction which has time of supply on or after 1st

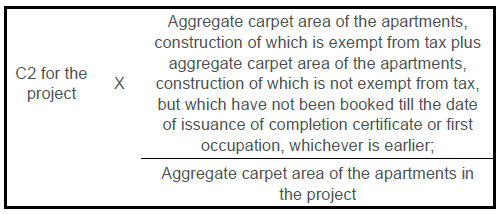

April, 2019. Simply put, the formula for determining the ITC reversible

is:

Essentially, therefore, the eligibility to claim input tax credit is now restricted

only for ongoing projects where the option to pay tax at lower rate of 1

per cent / 5 per cent was not exercised or commercial units in other

than RREP project where the tax rate continues to be 12 per cent.

Further, vide a Removal of Difficulty Order, Rule 42 was amended

prospectively requiring the taxpayer to, at the time of completion of

project / first occupation, whichever is earlier, reverse the input tax

credit proportionate to the unsold area at that time. The formula to

determine the input tax credit reversible, simply put is:

![]()

It may not be out of place to highlight that both under the legacy laws as

well as GST, no tax is leviable on sale of constructed units after the

receipt of completion certificate.

In this article, we have

attempted to identify the various issues which plague the industry and

probable resolutions available for the sector from the perspective of

input tax credit.

Input tax credit reversal on area sold after completion certificate / first occupation, whichever is earlier:

Controversy under service tax pre-GST regime

The

process of undertaking the activity of construction is a time-intensive

project. All the units which are sold up to the receipt of completion

certificate / first occupation, i.e., while construction activity is

underway are liable to tax. This means that when the taxpayer incurs

substantial expenditure on construction, including paying tax on the

inward supplies, he also gets the right to claim the credit of the taxes

so paid on the inward supplies as they are used / intended to be used

for making a taxable supply. If during this stage, the taxpayer sells

any unit, the said sale becomes taxable service / supply.

Under

the CCR, 2004, Rule 6 provided that the credit on inputs / input

services to the extent used for providing exempt services shall be

liable to be reversed in the prescribed manner. The said rules required

every taxable person engaged in providing taxable as well as exempt

services to determine the credit on inward supply of inputs / input

services availed and used for providing both, taxable as well as exempt

services and such person was eligible to claim credit only to the extent

such inward supplies were used for making taxable supplies based on the

ratio of taxable services to value of total services provided during

the relevant financial year. In other words, an assessee

was required to carry out an exercise on an annual basis to determine

the credit reversible u/r 6 to the extent inward supplies are used for

providing both, taxable as well as exempt services.

Despite Rule

6 clearly providing a method fordetermining CENVAT credit attributable

to exempt services, many taxpayers were served with notices raising

ademand by applying the provisions of Rule 6 on a project basis /

totality basis / area basis. For example, a builder starts a project in

2012 which is completed in 2016 (say 31st March, 2016). The various

details of the project are as under:

|

FY |

Total |

Total |

CENVAT |

|

2012-13 |

2,000 |

2,00,00,000 |

7,50,000 |

|

2013-14 |

5,000 |

5,00,00,000 |

6,50,000 |

|

2014-15 |

8,000 |

8,00,00,000 |

7,00,000 |

|

2015-16 |

1,500 |

1,50,00,000 |

4,25,000 |

|

2016-17 |

11,000 |

11,00,00,000 |

2,75,000 |

|

Total |

25,000 |

25,00,00,000 |

28,00,000 |

Notices were issued to taxpayers demanding reversal of

credit u/r 6 of CCR, 2004. The reversal was towards the proportionate

CENVAT credit availed by them during the period of construction, which

was ultimately also used for providing non-taxable service, i.e., sale

of units after receipt of completion certificate / first occupation. For

example, in this case, sale of 44 per cent of units would be

non-taxable and therefore, credit claimed towards area which did not

attract service tax, i.e., 44 per cent of the total area sold was

alleged as being liable to be reversed. Accordingly, notice demanding

Rs.12,32,000 was raised on the taxpayers (Rs. 28,00,000*11,000/25,000).

The

matter came up before the Hon’ble Ahmedabad bench of the CESTAT in the

case of Alembic Ltd. vs. CCE & ST, Vadodara I [2019 (28) G.S.T.L. 71

(Tri.-Ahmd)] wherein it was held that the eligibility / entitlement to

credit has to be examined only at the time of receipt of input service

and once it is found to be availed at a time when output service is

wholly taxable, the same is availed legitimately and cannot be denied

and / or recovered unless specific machinery provisions are made.

The

Revenue appeal against the Tribunal’s decision was dismissed by the

Hon’ble Gujarat High Court in 2019 (29) G.S.T.L. 625 (Guj.) wherein it

was held that since at the time of receipt of input services, there was

no exempt service provided by the Appellant, the question of

applicability of Rule 6 does not arise. Rule 6 became applicable only

after the completion certificate was obtained.

Controversy under GST – pre-amendment scenario

At the time of introduction of GST, in a manner similar to Rule 6 of CCR,

2004, the provisions under GST, i.e., Rule 42 provided for reversal of

input tax credit based on turnover of exempted supplies to total

turnover, i.e., exempt plus taxable when an inward supply is used for

making both, taxable as well as exempt supplies.

Rule 42

prescribed that the amount of input tax credit attributable towards

exempt supplies be denoted as D1 and the same be calculated as (D1=E÷F) x

C2. In the present context, E refers to the value of exempted supplies

i.e., the value of the flats sold post completion, F refers to the

aggregate value of exempted supplies as well as taxable supplies and C2

refers to the common credit pertaining to both exempted as well as

taxable supplies. It may further be noted that this formula is

applicable for each tax period. The term ‘tax period’ is defined to mean

the period for which the return is required to be furnished, which is

monthly in GSTR-3B and annually in GSTR-9. Therefore, each of the above

values needs to be calculated for each period and the disallowance

should be restricted to the period only after the taxable person starts

making exempt supplies. Necessarily, for effective implementation of

this Rule, the taxpayer should be simultaneously engaged in making

taxable and exempt supplies, which is likely to occur only when the

project is likely at the end stage.

In that sense, there is a

strong reason to believe that the decision of the Gujarat High Court in

the case of Alembic Ltd. shall apply to GST as well.

CONTROVERSY UNDER GST – POST-AMENDMENT SCENARIO

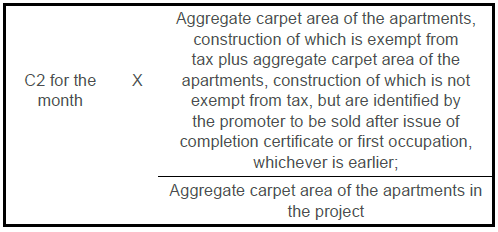

Rule

42 was amended w.e.f 01st April, 2019 to provide that for the value of

exempt supply shall be the aggregate carpet area of the apartments,

construction of which is exempt from tax plus aggregate carpet area of

the apartments, construction of which is not exempt from tax but are

identified by the promoter to be sold after issuance of completion

certificate or first occupation, whichever is earlier. Similarly, the

value of taxable supply shall be the aggregate carpet area of the

apartments in the project.

The above demonstrates that the

prescribed method for determining the amounts to be reversed on account

of input tax credit used for making exempt supplies shall be based on

area and not value, as provided for u/s 17 (3). Therefore, to overcome

this apparent conflict between the amended Rule and the provisions in

the Act, Removal of Difficulty Order No. April, 2019 – Central Tax dated

29th March, 2019 was issued vide which it was clarified that in case of

supply of services covered by clause (b) of paragraph5 of Schedule II

of the said Act, the amount of credit attributable to the taxable

supplies including zero rated supplies and exempt supplies shall be

determined on the basis of the area of the construction of the complex,

building, civil structure or a part thereof, which is taxable and the

area which is exempt.

The first question which arises is whether

the ROD is legally sustainable? To understand this aspect, we need to

refer to section 172 of the CGST Act, 2017 which empowers the Government

to issue such Order, which is reproduced below for reference:

(1)

If any difficulty arises in giving effect to any provisions of this

Act, the Government may, on the recommendations of the Council, by a

general or a special order published in the Official Gazette, make such provisions not inconsistent with the provisions of this Act or the rules or regulations made thereunder, as may be necessary or expedient for the purpose of removing the said difficulty:

Provided that no such order shall be made after the expiry of a period of three years from the date of commencement of this Act.

(2) Every order made under this section shall be laid, as soon as may be, after it is made, before each House of Parliament.

Reading

of the above provisions shows that section 172 empowers the Government

to make provisions to remove any difficulty which may arise in putting

the law into operation. However, the powers are to be exercised in such a

way that it does not change the basic policy of the Act in question. It

should not be inconsistent with the provisions of the Act. In the

present case, the ROD provides that ITC reversal in case of

constructions services shall be done based on carpet area of

construction of complex despite the section clearly providing that the

reversal of ITC shall be based on value. It is therefore clear that in

guise of ROD, a new provision has been introduced which creates hardship

or puts the taxpayer at a disadvantage. It is likely that such order

and amendment to Rule 42 may therefore be held to be unconstitutional as

ROD orders cannot be issued to change the basic provisions of the

section itself.

This principle has been followed by Courts on

multiple occasions. In Madeva Upendra Sinai vs. Union of India

[2002-TIOL-1189-SC-IT-CB], the Hon’ble Supreme Court has held that in

removal of difficulty, the Government can exercise the power only to the

extent it is necessary for giving effect to the Act. The basic or

essential provisions cannot be tampered with. Similar view has been

followed in Straw Products Ltd. vs. Income Tax Officer

[2002-TIOL-1564-SC-IT-CB] wherein it has been held that power to remove

difficulty can be exercised in the manner consistent with the scheme and

essential provisions of the Act. In Krishna Deo Misra vs. State of

Bihar and Ors. [AIR-1988-Pat 9], it has been held that ROD must not be

inconsistent with any provisions of the Parent Act. Also, ROD clause

cannot be used as a substitute for rule making power. In view of the

above, it can be said that the amendment to Rule 42 w.e.f 1st April,

2019 aided by the ROD 4/2019 is clearly unsustainable in law.

Even

if one opines to the contrary, i.e., the amendments introduced in Rule

42 for the sector are maintainable in law, the position can be

summarized as under:

PROJECTS UNDER THE OLD SCHEME

a)

Whether the amended provision would apply to ongoing projects where

the option to pay tax under the old scheme has been exercised will need

analysis. This is because the eligibility to claim input tax credit is

determined at the time of receipt of inputs / input services, as held by

the Larger Bench of Tribunal in the case of Spenta International Ltd.

vs. CCE, Thane [2007 (216) E.L.T. 133 (Tri. – LB)] wherein it has been

held as under:

10. In the light of the above discussion, we

answer the reference by holding that Cenvat credit eligibility is to be

determined with reference to the dutiability of the final product on the date of receipt of capital goods.

b)

Further, when the input tax credit was claimed upto 31st March, 2019,

the same would have already been subjected to the provision of Rule 42,

as applicable at that point of time. Therefore, by a subsequent

amendment, the input tax credit already claimed by the developer cannot

be altered.

PROJECTS UNDER NEW SCHEME

c) The

amended provision would not have any relevance for ongoing projects

where the option to pay tax under new scheme have been exercised or new

project classified as residential real estate project. This is because

in case of ongoing projects where the builder pays tax under the amended

rates, the taxpayer would be liable to reverse the input tax credit as

per notification 11/2017 – CT(Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 (as amended)

which has been claimed upto 31st March, 2019 and there will be no fresh

claim of credits w.e.f 1st April, 2019.

d) However, in case of

other than RREP project where the tax is payable under new rates, i.e.,

residential units are taxable at 5 per cent while commercial units

continue to be taxable at 12 per cent, Rule 42 will be applicable, and

the taxpayer will need to identify the input tax credit proportionate to

the taxable commercial units. There can always be a question as to how

to determine the input tax credit attributable to such residential

projects, which have been dealt with separately in the article.

CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING AMENDED RULE 42

The amended Rule 42 is sought to be implemented in the following manner:

a)

On a monthly basis, the input tax credit claimed is deemed to be C2,

i.e., used for effecting taxable as well as exempt supplies.

b)

The taxpayer shall be required to calculate input tax credit

attributable to exempt supplies by applying the following formula:

received / first occupation takes place, whichever is earlier, the total

input tax credit attributable to exempt supplies is to be determined by

modifying the above formula as under:

compared with amount determined at (c) above and the differential amount

is either to be reversed [if (b)<(c)] or to be reclaimed [if

(c)<(b)].

A project has been defined to mean a Real Estate Project or a

Residential Real Estate Project.

multiple projects, he would be required to maintain a separate account

for each project. The same would not be an issue as even for RERA, a

developer is required to maintain separate accounts for each project.

However, when a project involves multiple buildings, say two buildings

of which one is commercial and second residential and separate accounts

are maintained within the same project, the developer will be faced with

a peculiar situation. This is because while the input tax credit

relating to residential building will be T3 and therefore, not eligible

for input tax credit, rule 42 deems the value of T4, i.e., the amount of

input tax credit attributable to inputs and input services intended to

be used exclusively for effecting supplies other than exempted supplies

to be zero. This inter alia means that the entire ITC shall be subjected

to the reversal and the option of excluding the same from the formula

will not be available.

not be eligible to claim input tax credit attributable to residential

units, the input tax credit attributable to commercial units will be

subjected to the reversal u/r 42, which appears illogical.

there may be instances where a builder receives multiple completion

certificates. For instance, a builder constructing 12 floor building

(with 4 floors commercial and 8 floors residential) receives Completion

Certificate in parts with simultaneous occupation, as under:

|

Date of CC |

For floors |

|

April 2020 |

1 – 4 |

|

April 2021 |

5 – 8 |

|

April 2022 |

9 – 12 |

The question that arises is how will the taxpayer implement Rule

42 in the above scenario where a single project entails multiple

completion certificates? The probable solution for this situation would

be that when the first and second completion certificates are received,

the corresponding area will have to be treated as exempt and the final

calculation will be required only when the third CC is received, which

indicates completion of the project.

Sale of units post

receipt of completion certificate / first application can be treated as

exempt occupation – whether exempt supply?

The

requirement for reversal of proportionate input tax credit is

necessitated in view of provisions of sub-sections (1) to (4) of Section

17 of the CGST Act, 2017. Section 17 (2) provides that where goods or

services or both are used partly for effecting taxable supplies and

partly for exempt supplies, the amount of credit shall be restricted to

so much of the input tax as is attributable to the said taxable

supplies. Section 17 (3) thereon deals with determination of value of

exempt supply for the purpose of section 17 (2) and includes supplies on

which the recipient is liable to pay tax under RCM, transaction in

securities, sale of land and subject to clause (b) of paragraph 5 of

Schedule II, sale of building.

It is by virtue of section 17 (3)

that the value of units sold after receipt of completion certificate /

first occupation (whichever is earlier) which are not leviable to tax is

included in the value of exempt supply. However, the important question

that remains is whether the sale of units post receipt of completion

certificate is classifiable as exempt supply for section 17 (2) to

trigger in the first place? The term “exempt supply” has been defined

u/s 2 (47) as under:

(47) “exempt supply” means supply of any

goods or services or both which attracts nil rate of tax or which may be

wholly exempt from tax under section 11, or under section 6 of the

Integrated Goods and Services Tax Act, and includes non-taxable supply.

As

can be seen from the above, the term exempt supply covers only such

transactions which are supply of goods or services but specifically

exempted or are classifiable as non-taxable supply, i.e., supply of

goods or services or both which are not leviable to tax.

Let us

first analyse if the sale of unit after receipt of completion

certificate / first occupation is exempted from the purview of tax or

not? The sale of unit after receipt of completion certificate / first

occupation is not exempted from the purview of tax as the same is

excluded from the scope of supply itself. Similarly, non-taxable supply

means such supply which is not leviable to tax, i.e., under section 9 of

the CGST Act, 2017. What is excluded from the levy of tax is only

supply of alcoholic liquor for human consumption. In that context, it

can be said that even the petroleum products are not excluded from the

levy of GST, but rather it is deferred to a future date u/s 9 (2) of the

CGST Act, 2017

Therefore, sale of unit after receipt of

completion certificate / first occupation may not qualify as “exempt

supply”. Infact, a view can be taken that in view of Schedule III, the

activity does not qualify as supply u/s 7. Hence, once an activity is

not covered within the purview of supply, the question of it being a

taxable / exempt supply does not arise. Therefore, section 17 (2) does

not get triggered as the same applies only when exempt supply is being

made by the taxpayer. Having said so, one may need to recognize that

Section 17(3) includes sale of buildings after receipt of completion

certificate in the value of exempted supply. However, it can be argued

that merely including the value of units sold after the receipt of

occupation certificate / first occupation in the value of exempt supply

in section 17 (3) is not sufficient to trigger the applicability of

section 17 (2), which is a must for demanding reversal of input tax

credit. Accordingly, the requirement of reversal of proportionate input

tax credit at the time of receipt of completion certificate can be said

to be litigative.

ABATEMENT FOR VALUE OF LAND – WHETHER EXEMPT SUPPLY?

Sale

of constructed unit not covered under Schedule III is liable to tax for

which the rates have been prescribed under notification 11/2017-

CT(Rate) dated 28th June, 2017. It is in this taxable transaction where

there is an embedded element of sale of land or undivided share in land.

The question that therefore arises is whether the explanation, which

provides for a lower taxable value can be treated as an exemption

provided u/s 11 of the CGST Act, 2017 to fall within the purview of

exempt supply?

As mentioned above, notification 11/2017-CT

(Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 which prescribes the rate of tax for

services provides that in case of supply of service involving transfer

of land or undivided share of land, the value of supply shall be 2/3rd

of the total amount charged for such supply. This has been provided for

by way of Explanation to the notification which is reproduced below for

ready reference:

[2. In case of supply of service specified in

column (3), in items (i), [(ia), (ib), (ic), (id), (ie) and (If)]

against serial number 3 of the Table above, involving transfer of land

or undivided share of land, as the case may be, the value of such supply

shall be equivalent to the total amount charged for such supply less

the value of transfer of land or undivided share of land, as the case

may be, and the value of such transfer of land or undivided share of

land, as the case may be, in such supply shall be deemed to be one third

of the total amount charged for such supply.

Explanation — For the purposes of this paragraph [and paragraph 2A below, “total amount” means the sum total of —

(a) Consideration charged for aforesaid service.

(b)

Amount charged for transfer of land or undivided share of land, as the

case may be including by way of lease or sub-lease.]

The

question that needs analysis is whether the reduction for value of land

(deemed / actual) is granted u/s 11 of the CGST Act, 2017 or u/s 15 (5)

which provides for determining the value of specified supplies. Section

11 provides as under:

(1) Where the Government is satisfied

that it is necessary in the public interest so to do, it may, on the

recommendations of the Council, by notification, exempt generally,

either absolutely or subject to such conditions as may be specified

therein, goods or services or both of any specified description from the

whole or any part of the tax leviable thereon with effect from such

date as may be specified in such notification.

From the

above, it is seen that section 11 empowers the Government to exempt

goods or services or both from the whole or any part of the tax leviable

thereon. However, the fact remains that land, being immovable property

is not goods for the purpose of GST as goods include only moveable

property within its’ purview. The question that remains is whether land

can be treated as service? The answer to the same would be negative as

service traditionally is referred to an activity. Immovable property per

se is not an activity and therefore, cannot be treated as service.

However, any activity on or relating to immovable property may be a

service, for instance, renting / leasing of immovable property.

Therefore, sale of land, which is neither goods nor service and excluded

from the scope of supply, cannot be exempted by section 11 of the CGST

Act, 2017. In this context, one may refer to the conclusion of the

Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Larsen & Toubro Ltd. [2015 (39)

S.T.R. 913 (S.C.)] wherein it has been held as under:

44.

We have been informed by counsel for the revenue that several exemption

notifications have been granted qua service tax “levied” by the 1994

Finance Act. We may only state that whichever judgments which are in

appeal before us and have referred to and dealt with such notifications

will have to be disregarded. Since the levy itself of service tax has

been found to be non-existent, no question of any exemption would arise.

With these observations, these appeals are disposed of.

Therefore,

it cannot be said that the Explanation intends to provide exemption

from the supply. On the other hand, since the activity sought to be

taxed is a transaction involving supply of services as well as supply of

land, the reduction is clearly for determining the value of supply and

therefore, the explanation is for determining the value of supply, i.e.,

u/s 15 of the CGST Act, 2017.

This aspect needs to be analyzed

since if a view is taken that the value of land, for which a deduction

is provided under notification 11/2017 – CT(Rate) dated 28th June, 2017

is towards exempt supply, the corresponding expenses incurred by the

taxpayer would be hit by section 17 (2) r.w. Rule 42 and would be liable

for reversal as under:

- Input tax credit on expenses directly attributable towards acquisition of land / associated costs shall be classified as T2.

- Input tax credit on expenses used for making both, taxable as well as exempt supplies shall be classified as C2.

Let

us understand this with the help of an example. A builder takes land on

100-year lease from CIDCO for a proposed residential / commercial

project which he intends to sell to customers. CIDCO charged a one-time

lease premium of Rs. 30 crore and 18 per cent GST on the same, i.e., Rs.

5.40 crore. The lease would be transferred to the co-operative housing

society upon completion of the project. In addition to the lease

payments, the builder also incurs various expenses relating to the

acquisition of land, such as legal payments, soil testing, etc.

The input tax credit implications in light of the above discussion can be summarized as under:

a)

The reduction towards value of land cannot be attributable to supply

u/s 7 and therefore, the question of there being a taxable / exempt

supply does not arise. Therefore, since section 17 (2) does not get

triggered, section 17 (3) becomes inconsequential.

b) The

reduction towards value of land is not attributable to an exemption

provided u/s 11 and therefore, is not covered within the purview of

exempt supply.

c) In view of the above, a taxpayer is entitled

to claim input tax credit on expenses incurred towards acquisition of

land on which construction activity is undertaken even though no GST is

leviable on the amounts recovered from the clients towards the same, be

it on the actual / deemed basis.

Contrarily, a builder may take a

view that in order to claim input tax credit on the land costs, he may

forego the deduction for value of land and pay GST on the gross value

and claim full input tax credit. However, this option may not be

available in view of the recent decision of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in

the case of Interarch Builders Pvt. Ltd. [(2023) 6 Centax 40 (S.C.)].

In this case, the facts were that the assessee had opted to pay tax on

works contract services provided on the whole value, i.e., without

excluding the value of goods involved in the execution of such contract

and claimed correspondingly full CENVAT credit, including on inputs and

capital goods which was otherwise not eligible. Upon Appeal by the

Department, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that the contention of the

taxpayer that they have a legal right to pay tax even on the goods

portion as service tax and take input credit on the duty paid on the

goods is clearly contrary to para 25 of the decision in the case of

Larsen and Toubro [2015 (39) S.T.R. 913 (SC)] and Rule 2A of the

Valuation Rules, 2006 and proceeded to held that the taxpayer was liable

to pay tax only on the service component. This analogy can squarely be

extended to GST as the Court may very well hold that the liability to

pay tax was only on the construction services and not on the land

component.

Input tax credit on free area in re-development projects / government schemes

Land

in metro cities like Mumbai is a scarce commodity. Therefore, the

sector finds avenues to identify opportunities to recycle the land. This

is done by undertaking redevelopment projects wherein existing

structures are demolished and new structure is developed. While

undertaking this redevelopment activity, the builder is required to

provide alternate accommodation to the existing occupants. Similarly,

the Government also encourages the sector to take up slum rehabilitation

activities whereby the builder agrees to construct a new structure

where the slum occupants are rehabilitated in such buildings and the

developers are given construction rights to construct separate structure

for sale in open market.

When the builder undertakes

construction activity to the extent done for the existing occupants (in

case of re-development) / slum dwellers (in case of SRA project), the

question is whether the builder is eligible to claim input tax credit

corresponding to such free area in re-development / SRA projects?

Under

service tax regime, a dispute was raised on the taxability of such free

area and a demand was proposed on the taxpayers (on the output side).

The Tribunal in Vasantha Green Projects vs. Commissioner [2019 (20)

G.S.T.L. 568 (Tri. – Hyd.)] has held that no service tax was payable on

such free area as the price collected from the customers also factored

the cost incurred towards construction of the free area and therefore,

no service tax was separately leviable on such free area. The conclusion

of the Hon’ble Tribunal will squarely apply to the claim of input tax

credit since the builder can very well claim that the input services

attributable to the free area is ultimately used for providing taxable

service and therefore, input tax credit is eligible. This logic will

squarely apply under GST regime as well.

However, another issue

which may arise under GST is whether the claim of input tax credit to

the extent it pertains to free area is hit by section 17 (5) (h) which

restricts claim of input tax credit on goods lost, stolen, destroyed,

written off or disposed of by way of gift or free samples? The answer to

this would be in negative. This is because what is given free to the

existing occupants / slum dwellers is not any goods, but rather a

constructed area which is an outcome of a composite supply. Secondly, in

the course of undertaking this construction activity, the builder also

receives various input services to which this restriction does not

apply. Readers may kindly note that this discussion will be relevant

only for projects concluded up to 31st March, 2019 since input tax

credit is denied for RREPs after 01st April, 2019.

CONCLUSION

When

GST was introduced, input tax credit was expected to flow seamlessly

and avoid cascading effect of taxes. Till 31st March, 2019, the sector

did enjoy the benefit of input tax credit which was not available under

the legacy laws. However, the amendment w.e.f 01st April, 2019 keeping

the sector in mind has left the sector worse off as compared to the

legacy laws, i.e., service tax. It is therefore imperative that before

claiming any input tax credit, the various conditions and restrictions

prescribed for the sector be analyzed carefully to avoid subsequent

litigation.