By Mayur B. Nayak | Tarunkumar G. Singhal | Anil D. Doshi | Mahesh Nayak

Chartered Accountants

In our earlier articles of January and May, 2020, we had covered the proposals discussed between the countries participating in the Inclusive Framework to tax the digitised economy. Closer home, India has introduced several provisions to bring into the tax net the income of the digitised economy – Equalisation Levy (EL), Significant Economic Presence (SEP) and Extended Source Rule for business activities undertaken in or with India.

This article seeks to analyse the provisions introduced in the Income-tax Act, 1961 (the Act) to tax the income in the digitised economy era – Explanation 2A, i.e., SEP, and Explanation 3A, i.e., the extended source rule, to section 9(1)(i). While there are other measures and provisions relating to taxation of the digitalised economy, such as EL and provisions related to deduction and collection of taxes, this article does not deal with such provisions.

1. BACKGROUND

Taxation of the digitised economy has been one of the hotly debated topics in the international tax arena in the recent past, not just amongst tax practitioners and academicians but also amongst governments and revenue officials. The existing tax rules are not sufficient to tax the income earned in the digital economy era. The existing rules of allocation of taxing rights in DTAAs between countries rely on physical presence of a business in a source country to tax income. However, with the advent of technology, the way businesses are conducted is different from that a few years ago. Today, it is possible to undertake business in a country without requiring any physical presence, thereby leading to no tax liability in the country in which such business is undertaken.

The urgency and importance of this topic became evident when OECD included taxation of the digital economy as the first Action Plan out of 15 in the BEPS Project. More than 130 countries, as part of the Inclusive Framework of the OECD, have been seeking to arrive at a consensus-based solution to tax the transactions in the digitised economy era for the past few years. In this regard, a two-pillar Unified Approach has been developed and the blueprints for both the Pillars were released for public comments in October, 2020.

While countries in the Inclusive Framework are hopeful of arriving at a consensus amongst all members this year, there are various policy considerations which need to be taken into account. Further, the UN Committee of Experts on International Co-operation in Tax Matters has also tabled a proposal seeking to insert a new article in the UN Model Double Tax Convention to tax the digitised economy.

India has been a key player in the global discussions to tax the digitised economy. While BEPS Action Plan 1 dealing with taxation of the digital economy did not provide a recommendation in the Final Report released in October, 2015 on account of the lack of consensus amongst the participating countries, the Report analysed (without recommending) three options for countries until consensus was arrived at – withholding tax, a digital permanent establishment in the form of SEP, or equalisation levy. It was also concluded that member countries would continue to work on a consensus-based solution to be arrived at at the earliest.

DEVELOPMENTS IN INDIA

India was one of the first countries to enact a law in this regard and EL was introduced as a part of the Finance Act, 2016. The EL applicable to online advertisement services was not a part of the Act and therefore, arguably, not restricted by tax treaties. The Finance Act, 2018 introduced the SEP provisions in the Act. Further, the scope of ‘income attributable to operations carried out in India’ was extended by the Finance Act, 2020. While introducing the extended scope, the Finance Act, 2020 also amended the SEP provisions and postponed the application of these provisions till the F.Y. 2021-22. Further, the Finance Act, 2020 also expanded the scope of the EL provisions.

Unlike the EL provisions, SEP by insertion of Explanation 2A to section 9(1)(i) and the Extended Source Rule by insertion of Explanation 3A to section 9(1)(i), were introduced in the Act itself and hence the taxation of income covered under these provisions may be subject to the beneficial provisions of the tax treaties.

In other words, the application of these provisions would be required in a scenario where the non-resident is from a jurisdiction which does not have a DTAA with India, or where the non-resident is not eligible to claim benefits of a DTAA, say on account of application of the MLI provisions, or due to the non-availability of a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC).

In addition to scenarios where benefit of the DTAA is not available, it is important to note that one of the possible methods for implementation of Pillar 1 of the Unified Approach is the modification of the existing DTAAs through another multilateral instrument (MLI 2.0) to provide for a nexus and the amount to be taxed in the Country of Source or Country of Market. Therefore, the reason for introduction of these provisions in the Act is to enable India to tax such transactions once the treaties are modified because without charge of taxation in the domestic tax law, mere right provided by a tax treaty may not be sufficient.

2. EXPLANATION 2A TO SECTION 9(1)(I) (SEP)

The SEP provisions were introduced by way of insertion of Explanation 2A to section 9(1)(i) of the Act. It reads as follows:

‘Explanation 2A. – For the removal of doubts, it is hereby declared that the significant economic presence of a non-resident in India shall constitute “business connection” in India and “significant economic presence” for this purpose, shall mean –

(a) transaction in respect of any goods, services or property carried out by a non-resident with any person in India, including provision of download of data or software in India, if the aggregate of payments arising from such transaction or transactions during the previous year exceeds such amount as may be prescribed; or

(b) systematic and continuous soliciting of business activities or engaging in interaction with such number of users in India, as may be prescribed:

Provided that the transactions or activities shall constitute significant economic presence in India, whether or not –

(i) the agreement for such transactions or activities is entered in India; or

(ii) the non-resident has a residence or place of business in India; or

(iii) the non-resident renders services in India:

Provided further that only so much of income as is attributable to the transactions or activities referred to in clause (a) or clause (b) shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India.’

Therefore, Explanation 2A seeks to extend the definition of ‘business connection’ to certain transactions where the business is undertaken ‘with’ India as against the traditional method of creating a business connection only in cases of transactions undertaken ‘in’ India.

The thresholds in respect of the amount of payment for goods and services and in respect of the number of users have not yet been prescribed, therefore the provisions of SEP, although applicable from A.Y. 2022-23, are not yet operative.

2.1 Whether SEP would apply only in case of digital transactions

It is important to note that under Explanation 2A, the definition of SEP is an exhaustive one and therefore a transaction which does not satisfy the above criteria would not be considered as constituting an SEP.

It is also important to note that the definition of SEP is not restricted to only digital transactions but seeks to cover all transactions which are undertaken with a person in India. This is in line with the proposed provisions of Pillar 1 of the Unified Approach and the discussion of the same in the Inclusive Framework. Pillar 1 of the Unified Approach seeks to bring to tax automated digital businesses as well as consumer-facing businesses. On the other end of the spectrum, the proposed Article 12B in the UN Model Tax Convention seeks to tax only automated digital businesses and does not cover consumer-facing businesses.

Further, at the time of introduction of the SEP provisions in the Finance Act, 2018, the Memorandum explaining the provisions of the Finance Bill (Memorandum) referred to taxation of digitalised businesses and thus the intention seems to be to tax transactions undertaken only through digital means. However, the language of the section does not suggest the taxation only of digital transactions. This is also evident in the CBDT Circular dated 13th July, 2018 (2018) 407 ITR 5 (St.) inviting comments from the general public and stakeholders, specifically comments on revenue threshold for transactions in respect of physical goods.

Further, with regard to clause (a) what needs to be prescribed is the threshold for the amount of payment and not the type of transactions covered. Therefore, even a transaction undertaken through non-digital means would constitute an SEP in India and hence a business connection in India if the aggregate transaction value during the year exceeds the prescribed amount.

An example of a transaction which may possibly be covered subject to the threshold could be the service provided by a commission agent in respect of export sales, wherein no part of the service of such agent is undertaken in India. Various judicial precedents have held that export sales commission is neither attributable to a business connection in India in such a scenario, nor does it constitute ‘fees for technical services’ u/s 9(1)(vii) of the Act. However, now the activities of such an agent, providing services to a person residing in India (the seller), could possibly constitute an SEP in India.

Further, clause (b) above refers to systematic and continuous soliciting of business or engaging in interaction with a prescribed number of users. At the time of the introduction of the SEP provisions by the Finance Act, 2018, this activity was required to be undertaken ‘through digital means’ in order to constitute an SEP. This additional condition of the activity being undertaken ‘through digital means’ was removed by the Finance Act, 2020. Accordingly, any activity which is considered

as soliciting business or engaging with a prescribed number of users could result in the constitution of an SEP in India.

For example, a call centre of a bank outside India which deals with a number of Indian customers could result in the entity owning the call centre to be considered as having an SEP in India if the number of customers solicited exceeds the prescribed threshold.

Accordingly, every type of transaction undertaken with India may be covered as constituting an SEP in India, not in accordance with what is provided in the Memorandum.

2.2 Transaction in respect of any goods, services or property carried out by a non-resident with any person in India

The first condition for constitution of an SEP is a transaction in respect of any goods, services or property carried out by a non-resident with any person in India, the payments for which exceed the prescribed threshold.

The term ‘goods’ has not been defined in the Act. While one may be able to import the definition of the term from the Sale of Goods Act, 1930, it may not be of much relevance as the SEP provisions also apply to transactions in respect of ‘property’. Therefore, all assets, tangible as well as intangible, would be covered under this clause subject to the discussion below regarding SEP covering only transactions whose income is taxed as business profits.

Thus, offshore sale of goods to a person in India may now be covered under the SEP provisions (subject to the fulfilment of the threshold limit). Interestingly, the Supreme Court in the case of Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries Ltd. vs. DIT [2007] 288 ITR 408, held that income from sale of goods by a non-resident concluded outside India would not be considered as income accruing or arising in India. The SEP provisions, specifically covering such transactions, could now override the decision of the Apex Court in cases where the SEP provisions are triggered.

Another question that arises is whether a transaction of sale of shares is covered. Let us take as an example the sale of shares of a US Company by a US resident to a person in India. Such a sale, not being sale of shares of an Indian company, assuming that the US Company does not have an Indian subsidiary to trigger indirect transfer provisions, was not considered as accruing or arising in India and therefore is not taxable in India.

In the present case, one may be able to argue that even if the transaction value exceeds the threshold limit, the SEP provisions would not be triggered if the sale is not a part of the business of the US resident seller. This would be so as the constitution of an SEP results in the constitution of a business connection. Therefore, for SEP to be constituted, the transaction needs to be in respect of business income and not in respect of a capital asset. Section 9(1)(i) clearly differentiates between business connection and an asset situated in India.

In other words, SEP would only apply to transactions, the income from which would constitute business income. Accordingly, income from sale of shares, not being the business income of the US resident seller, would not trigger SEP provisions.

It is important to highlight that what is sought to be covered under the SEP provisions is business income and a transaction of sale of property which is not a part of the business of the non-resident seller may not be covered. However, this does not mean that a single transaction is outside the scope of SEP provisions. Let us take the example of a heavy machinery manufacturer in Germany who sells his machines globally. If the price of a single machine exceeds the threshold value, a single sale by the German manufacturer to a person in India may trigger the SEP provisions as the income from such sale is a part of his business income. While the Supreme Court in the case of CIT vs. R.D. Aggarwal & Co., (1965) (56 ITR 20, 24), held that a stray or isolated transaction is normally not to be regarded as a business connection, this position may no longer hold good for transactions triggering SEP as the SEP provisions require fulfilment of subjective conditions.

But then, what is meant by a ‘person in India’? While most of the sections in the Act refer to a ‘person resident in India’, Explanation 3A refers to a ‘person who resides in India’. Given the intention to tax a non-resident on account of the economic connection with India, there needs to be a semblance of permanent connection of the transaction with India. This permanent connection may not be satisfied in the case of a person who is visiting India for a short visit and is, say, availing the services from the non-resident. Therefore, one may argue that a person in India in Explanation 2A would mean a person resident in India. Further, the term ‘resides’ may connote a continuous form of residence and, therefore, in such a scenario also, one may be able to argue that the term refers to a person resident in India.

2.3 Systematic and continuous soliciting of business activities or engaging in interaction with such number of users in India

The second condition for the constitution of an SEP is systematic and continuous soliciting of business activities or engaging in interaction with a prescribed number of users in India.

There are two types of transactions which would be covered under the condition (subject to the fulfilment of the number of users in India threshold):

a) Systematic and continuous soliciting of business activities; and

b) Engaging in interaction.

There is ambiguity as to what constitutes ‘users’, ‘soliciting’ as well as ‘engaging in interaction’. As highlighted earlier, while the conditions required the above activities to be undertaken through digital means at the time SEP provisions were introduced by the Finance Act, 2018, the Finance Act, 2020 removed the requirement of digital means, thereby possibly expanding the scope of the transactions covered.

We need to wait and see how the threshold limits along with conditions, if any, are prescribed.

Some of the activities which may be covered under this condition would be social media companies, support services which engage with multiple users in India, online advertisement services, etc.

2.4 Profits attributable to SEP

The second proviso to Explanation 2A provides that only so much of income as is attributable to the transactions or activities referred to in clause (a) or clause (b) shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India. Explanation 1(a) to section 9(1)(i), on the other hand, seeks to cover income attributable to operations carried out in India.

Given the peculiar language used in the 2nd proviso to Explanation 2A, this may result in a scenario where the entire income arising out of a transaction or activity would be considered as accruing or arising in India.

Let us take an example to understand the impact and such a possible absurd outcome in detail. A non-resident who manufactures certain goods outside India sells such goods in India under two scenarios – through a sales office in India and directly without any physical presence in India. Assuming that in both scenarios the sale of the goods is concluded outside India, in the first scenario the activities undertaken by the sales office could result in the constitution of business connection under Explanation 2 if the employees in the sales office habitually play a principal role in the conclusion of contracts of the non-resident in India. In such a scenario, Explanation 3 provides that only the income as is attributable to the activities of the sales office would be deemed to accrue or arise in India. Therefore, only a part of the profits of the non-resident, which represents the amount attributable to the activities of the sales office, let us say xx% on the basis of various judicial precedents, would be taxable in India.

However, in the second scenario, assuming that the threshold as prescribed in Explanation 2A is met, the transaction of the sale of goods to a person resident in India could constitute an SEP in India. In such a scenario, the moot question that arises for consideration is whether on a literal reading of the 2nd proviso to Explanation 2A, it can be said that in such a transaction the entire income is attributable to the ‘transaction’ and shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India?

In other words, if a business connection is constituted on account of operations carried out in India, only part of the profits would be taxed in India, whereas if the business connection is constituted on account of the SEP in India, it is open to question as to whether the entire income of the non-resident could be attributed and deemed to accrue or arise in India.

Similarly, the entire income of a social media company outside India engaging with a large number of users in India could be taxed in India if the number of users exceeds the threshold and results in the constitution of an SEP in India.

Such a view, on a literal interpretation of the amended provisions, would not be in consonance with the global discussion on the subject currently in progress at various international fora.

Such a view would also not be in line with the discussion contained in the BEPS Action Plan 1 Report which provides:

‘Consideration must therefore be given to what changes to profit attribution rules would need to be made if the significant economic presence option were adopted, while ensuring parity to the extent possible between enterprises that are subject to tax due to physical presence in the market country (i.e., local subsidiary or traditional PE) and those that are taxable only due to the application of the option.’

Further, the BEPS Action Plan 1 Report analyses three options while attributing profits to the SEP:

a) Replacing functional analysis with an analysis based on game theory that would allocate profits by analogy with a bargaining process within a joint venture. However, the Report appreciates that this method would mean a substantial departure from the existing standard for allocation of profits on the basis of functions, assets and risks and, therefore, unless there is a substantial rewrite of the rules for the attribution of profits, alternative methods would need to be considered;

b) The fractional apportionment method wherein the profits of the whole enterprise relating to the digital presence would be apportioned either on the basis of a predetermined formula or on the basis of variable allocation factors determined on a case-by-case basis. However, this method is not pursued further as it would mean a departure from the existing international standard of attributing profits on the basis of separate books of the PE;

c) The deemed profit method wherein the SEP for each industry has a deemed net income by applying a ratio of the presumed expenses to the taxpayer’s revenue derived in the country. While this option is relatively easier to administer, it has its own set of challenges, such as, if the entity on a global level has incurred a loss, would the deemed profit method still allocate a notional profit to the SEP?

Similarly, the draft Directive, introduced by the European Commission on ‘significant digital presence’, provided for a modified profit-split as the method to attribute the profits to the SEP. The draft Directive, introduced in 2018, was not enacted due to lack of consensus amongst the members of the European Union.

In both the examples above, in the context of profits attributable to the SEP, one may be able to argue that taxing activities undertaken outside India result in extra-territorial taxation by India and, therefore, go beyond the sovereign right of the country to tax such income.

The CBDT has recognised this need to provide clarity for profit attribution to the SEP and has included a chapter on the same in its draft report on Profit Attribution to Permanent Establishments (CBDT Press Release F 500/33/2017-FTD.I dated 18th April, 2019) (draft report).

The draft report provides that in the case of an SEP, in addition to the traditional equal weightage given to assets, employees and sales, one can consider giving weightage to users as well in the case of digitised businesses depending on the level of user intensity. The draft report proposes the weight of 10% to users in business models involving low / medium user intensity and 20% in business models involving high user intensity.

It is important to note that the report, when finalised and notified, would be forming a part of the Rules and in the absence of any reference to attribution of profits to the SEP in Explanation 2A, one may need to further analyse the application on finalisation of the rules.

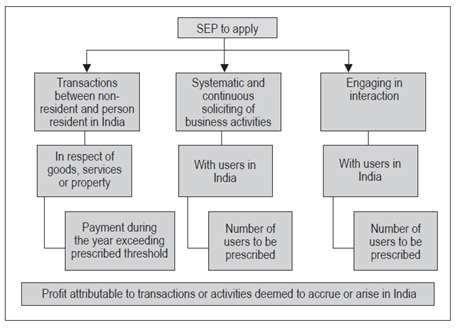

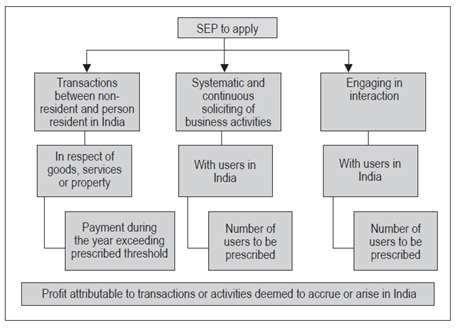

2.5 Summary of SEP provisions

The SEP provisions have been summarised below:

3. EXPLANATION 3A TO SECTION 9(1)(i) (EXTENDED SOURCE RULE)

Following global discussions, the Finance Act, 2020 extended the source rule for income attributable to operations carried out in India by inserting Explanation 3A to section 9(1)(i), which reads as under:

‘Explanation 3A. – For the removal of doubts, it is hereby declared that the income attributable to the operations carried out in India, as referred to in Explanation 1, shall include income from –

(i) such advertisement which targets a customer who resides in India or a customer who accesses the advertisement through an internet protocol address located in India;

(ii) sale of data collected from a person who resides in India or from a person who uses an internet protocol address located in India; and

(iii) sale of goods or services using data collected from a person who resides in India or from a person who uses an internet protocol address located in India.’

The following proviso has been inserted in Explanation 3A to clause (i) of sub-section (1) of section 9 by the Finance Act, 2020 w.e.f. 1st April, 2022:

‘Provided that the provisions contained in this Explanation shall also apply to the income attributable to the transactions or activities referred to in Explanation 2A.’

3.1 Whether Explanation 3A creates nexus?

Unlike Explanation 2A, which equates SEP to a business connection, the language used in Explanation 3A is different.

Explanation 3A to section 9(1)(i) provides,

‘For the removal of doubts, it is hereby declared that the income attributable to the operations carried out in India, as referred to in Explanation 1, shall include….’

Explanation 1 provides that in the case of a business of which all the operations are not carried out in India, only part of the income as is reasonably attributable to the operations carried out in India shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India.

Further, the nexus for income deemed to accrue or arise in India in the form of business connection in India or property in India or source of income in India, etc., is provided in the main section 9(1)(i).

Now, the question arises whether Explanation 1 can be applied without a nexus in section 9(1)(i)? One may argue that having established a nexus in the form of business connection, asset or source of income in India, Explanation 1 merely provides the amount of income attributable to the said nexus and, therefore, in the absence of a nexus u/s 9(1)(i), Explanation 1 cannot be applied.

In this regard, the role of ‘Explanation’ in a tax statute has been explained by the Karnataka High Court in the case of N. Govindraju vs. ITO (2015) (377 ITR 243) in the context of Explanation vs. proviso, wherein it was held,

‘37. Insertion of “Explanation” in a section of an Act is for a different purpose than insertion of a “proviso”. “Explanation” gives a reason or justification and explains the contents of the main section, whereas “proviso” puts a condition on the contents of the main section or qualifies the same. “Proviso” is generally intended to restrain the enacting clause, whereas “Explanation” explains or clarifies the main section. Meaning, thereby, “proviso”’ limits the scope of the enactment as it puts a condition, whereas “Explanation” clarifies the enactment as it explains and is useful for settling a matter or controversy.

38. Orthodox function of an “Explanation” is to explain the meaning and effect of the main provision. It is different in nature from a “proviso” as the latter excepts, excludes or restricts, while the former explains or clarifies and does not restrict the operation of the main provision. It is true that an “Explanation” may not enlarge the scope of the section but it also does not restrict the operation of the main provision. Its purpose is to clear the cobwebs which may make the meaning of the main provision blurred. Ordinarily, the purpose of insertion of an “Explanation” to a section is not to limit the scope of the main provision but to explain or clarify and to clear the doubt or ambiguity in it.’

The above decision lends weight to the argument that in the absence of a nexus in section 9(1)(i), Explanation 1 cannot apply. Having taken such a view, one may therefore possibly conclude that as Explanation 1 does not create a nexus and as Explanation 3A merely extends the scope of Explanation 1 in terms of income as is attributable to the operations carried out in India, Explanation 3A shall not apply unless the non-resident has a business connection. In other words, Explanation 3A merely acts like a ‘force of attraction’ provision in the Act and does not create a nexus by itself.

It may be highlighted that the above view that in the absence of a nexus u/s 9(1)(i), Explanation 1 shall not apply, is not free from doubt. Another possible view is that Explanation 1 refers to the income which is deemed to accrue or arise in India and therefore creates a nexus by itself irrespective of the fact as to whether or not there exists a business connection. One will have to wait for the judicial interpretation in this regard to see whether the judiciary reads down the extended source rule in Explanation 3A.

3.2 What is sought to be taxed through Explanation 3A

Explanation 3A seeks to extend the scope of income attributable to operations carried out in India in the case of three scenarios:

a) Sale of advertisement;

b) Sale of data; and

c) Sale of goods or services using data.

In respect of (a) and (b) above, the same is also covered by the extended EL provisions as applicable to e-commerce supply or services. Further, section 10(50) of the Act, as proposed to be amended by the Finance Bill, 2021, provides that income other than royalty or fees for technical services shall be exempt under the Act if the said transaction is subject to EL. Therefore, in respect of transactions covered under (a) or (b), the provisions of EL would apply and Explanation 3A may not be applicable.

Therefore, only the provisions of (c) have been analysed.

While Explanation 2A seeks to cover a transaction of a non-resident with a person residing in India, Explanation 3A does not require such conditions. In other words, even transactions between two non-residents may be subject to tax under Explanation 3A if the transaction:

a) In the case of sale of advertisement, targets a customer residing in India;

b) In the case of sale of data, is in respect of data collected from a person residing in India; or

c) In the case of sale of goods or services, is using data collected from a person residing in India.

For example, ABC, a foreign company owning a social media platform having various users all over the world, including India, is engaged by FCo, a foreign company engaged in the business of apparels, to provide data analytics services to enable FCo to understand the consumption pattern in Asia in order to enable it to target customers in Europe. It is assumed that the data analytics service is undertaken outside India.

In this scenario, as ABC is providing a service to FCo, both non-residents, using data collected from persons residing in India in addition to other countries, Explanation 3A may apply and, therefore, deem the income from sale of services to be accruing or arising in India. While, arguably, only the portion of the income which relates to the data collected from India should be taxed in India, it may be practically difficult, if not impossible, in such a scenario to bifurcate such income on the basis of data collected from every country.

Moreover, as this would be a transaction between two non-residents, the question of extra-territoriality as well as the practical difficulty of implementing the taxation of such transactions may need to be evaluated in detail.

The issues relating to the attribution of income – whether the entire income is deemed to accrue or arise in India or is only a part of the income (and if so, how is the same to be computed) is to be taxed, as explained above in the context of SEP would equally apply here as well. In fact, as the CBDT draft report on profit attribution to PE was released before the Finance Act, 2020, there is no guidance available to provide clarity in this matter.

4. CONCLUSION

Currently, the provisions of SEP are not yet operative as the thresholds have not yet been prescribed. Further, the SEP provisions as well as those related to extended scope have limited application due to the benefit available in the DTAAs. However, with treaty eligibility being questioned in various transactions in the recent past and with the application of the MLI, these provisions may be of greater significance. Therefore, it is imperative that some of the aforementioned ambiguities, such as the amount of income attributable to the SEP and extended scope, be clarified at the earliest by the authorities.