Introduction:

Section 4 and section 5 r.w.s. 9(1)(vi) of the Incometax Act, 1961 (the Act) provide for taxability of income from royalty in India. Section 9(1)(vi) of the Act by a deeming fiction provides for the taxation of income from royalty in India. Explanation 2 to section 9(1)(vi) of the Act defines the word ‘royalty’, which is wide enough to cover both industrial royalties as well as copyright royalties, both being forms of intellectual property. Computer software is regarded as an ‘industrial royalty’ and/or a ‘copyright royalty’. Industrial properties include patents, inventions, process, trademarks, industrial designs, geographic indicators of source, etc. and are generally granted for an article or for the process of making such article, on the other hand, copyright property includes literary and artistic works, plays, films, musical works, knowledge, experience, skill, etc. and are generally granted for ideas, principles, skills, etc.

Just as tangible goods are sold, leased or rented in order to earn monetary gain, on similar lines, the Intellectual Property laws enable authors of the intellectual properties to exploit their work for monetary gain. The modes of exploitation of intellectual property for monetary gains are different for each type of intellectual property covered in various sub-clauses of the definition of ‘royalty’ under Explanation 2 to section 9(1)(vi) and subjected to tax as per the scheme of the Act.

The controversy on taxability of cross-border software payments basically relates to characterisation of the income in the hands of the non-resident payee. The controversy, sought to be discussed here, revolves around the issue “whether the payment received by non-resident for giving licence of the computer software, popularly known as ‘sale of software’, is chargeable to tax as ‘royalty’, or it is a ‘sale’. The Revenue holds such sales to be royalty on the ground that during the course of sale of computer software, computer program embedded in it is also licensed and/or parted with the end-user of the software, and as against the claim of the taxpayers who treat the transaction as one of transfer of ‘copyrighted article’ and not transfer of the right in the copyright or licence of the software. Typically the tax authorities seek to tax these payments in the hands of non-residents as royalty and subject the same to withholding taxes. The non-resident payees seek to label such receipts as business income not chargeable to tax, in the absence of a Permanent Establishment in India. Taxability of software-related transaction depends upon the nature and extent of rights granted or transferred under the particular arrangement regarding use and exploitation of the program.

Determining the taxability of any cross-border software transaction involves an understanding and analysis of the following aspects:

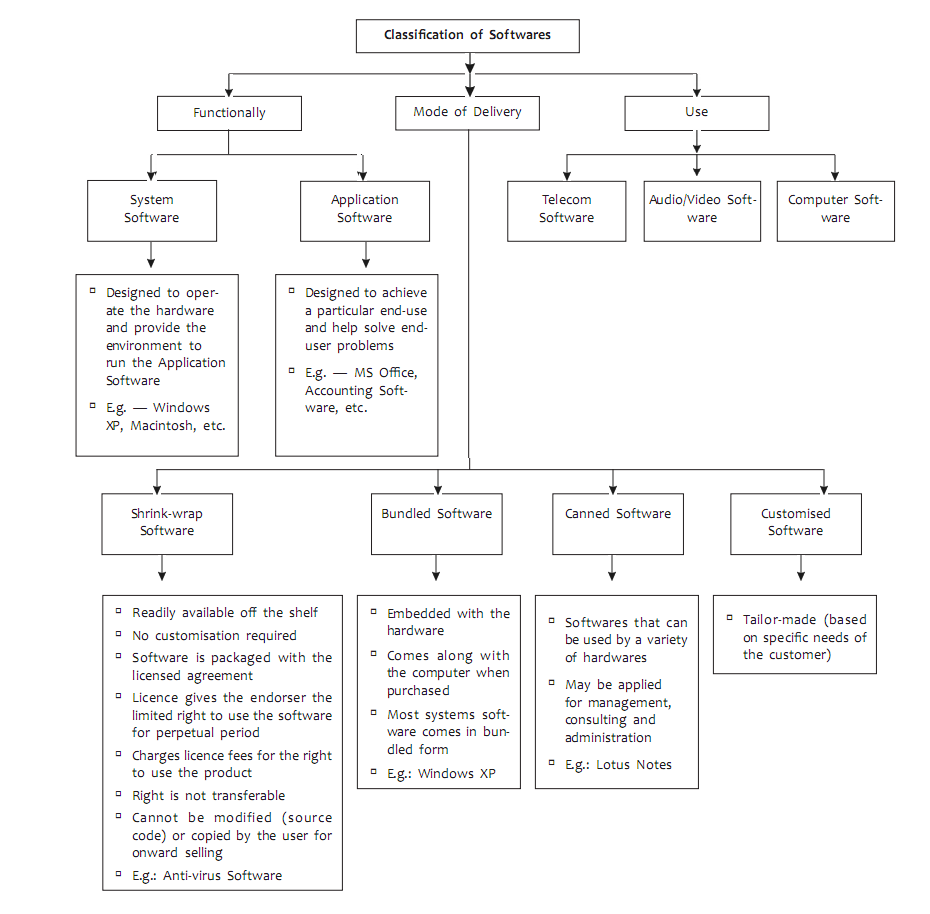

I. Definition and classification of Computer Software;

II. Definitions of Royalty under the Act and Double Tax Avoidance Agreement (DTAA);

III. Relevant provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957;

IV. OECD Commentary on Software Payments; and

V. Key judicial and advance rulings.

I. Definition and classification of Computer Software

Definition: Income-tax Act: Explanation 3 to Section 9(i)(vi) of the Act defines ‘Computer Software’ to mean any computer program recorded on any disc, tape, perforated media or other information storage device and includes any such program or any customised electronic data.

Copyright Act: Under the Indian Copyright law (Copyright Act, 1957), computer program and computer databases are considered literary works.

Section 2(ffc) defines ‘Computer Programme’ as a set of instructions expressed in words, codes, schemes or any other form, including a machine-readable medium, capable of causing a computer to perform a particular task or achieve a particular result.

Commentary on Article 12 of the OECD Model Convention describes software as a program, or series of programs, containing instructions for a computer required either for the operational processes of the computer itself (operational software) or for the accomplishment of other tasks (application software).

The New Oxford Dictionary for the Business World defines ‘software’ as programs used with a computer (together with their documentation), including program listings, program libraries, and user and programming manuals.

Typical Business Model relating to computer software:

- Single End-user model — Foreign Company supplies a single copy of the software to the end-user.

- Distributor Model — Foreign Company either supplies soft copies to an independent distributor in India for onward distribution to Indian customers either directly or through distribution channels or supplies a single copy of the software to a distributor in India who is given the licence to make copies and distribute soft copies to the customers.

- Multiple-user licence model — Foreign Company supplies a single disk containing the software program to an Indian Company with a right to make copies of the software and distribute to in-house end users.

- Customised model — Foreign Company customises the software as per Indian buyer’s requirements/ specifications — Enterprise Resource Planning software.

- Software embedded in hardware — Foreign Company supplies integrated equipment (software bundled with hardware).

- Cost contribution model — Foreign Company incurs expenditure for installation and maintenance of software system for the benefit of the group companies. It provides access to such Indian group company to use the system and recharges the cost on the basis of use of the system.

- Electronic model — Payment to Foreign Company for purchase of software through electronic media.

- Payment to Foreign Company for provision of services for development or modification of the computer program (incl. for upgradation, training, installation, maintenance, etc.).

- Payment to Foreign Company for know-how related to computer programming techniques.

- Definition of Royalty

Under the Act:Explanation 2 to Section 9(i)(vi) of the Act defines the term ‘Royalty’ to mean consideration for:(i) the transfer of all or any rights (including the granting of a licence) in respect of a patent, invention, model, design, secret formula or process or trademark or similar property;

(ii) …………….

(iii) …………….

(iv) …………….

(v) …………….

(vi) the transfer of all or any rights (including the granting of a licence) in respect of any copyright, literary, artistic or scientific work including films or video tapes for use in connection with television or tapes for use in connection with radio broadcasting, but not including consideration for the sale, distribution or exhibition of cinematographic films; or

(vii) the rendering of any services in connection with the activities referred to above in subclauses (i) to (iv), (iva) and (v).

Under the DTAA:

Most DTAAs define the term ‘royalty’ to mean:

(i) payments of any kind received as a consideration for the use of, or the right to use, any copyright of a literary, artistic, or scientific work, including cinematograph films or work on films, tape or other means of reproduction for use in connection with radio or television broadcasting, any patent, trademark, design or model, plan, secret formula or process, or for information concerning industrial, commercial or scientific experience; and

(ii) payments of any kind received as consideration for the use of, or the right to use, any industrial, commercial, or scientific equipment, other than payments derived by an enterprise of a Contracting State from the operation of ships or aircraft in international traffic.

III. Relevant provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957

Section 2(o): Literary Work

includes computer programs, tables and compilations including computer databases.

Section 14: Meaning of Copyright:

Copyright means the exclusive right, subject to the provisions of this Act, to do or authorise the doing of any of the following acts in respect of a work or any substantial part thereof, namely;

(i) in the case of a literary, dramatic or musical work, not being a computer program —

(a) to reproduce the work in any material form including the storing of it in any medium by electronic means;

(b) to issue copies of the work to the public and not being copies already in circulation;

(c) to perform the work in public, or communicate it to the public

(d) to make any cinematograph film or sound recoding in respect of the work

(e) to make any translation of the work

(f) to make any adaptation of the work

(g) to do, in relation to a translation or an adaptation of the work, any of the acts specified in relation to the work in sub-clauses

(i) to (vi).

(ii) in the case of computer program —

(a) to do any of the acts specified in clause (a) above;

(b) to sell or give on commercial rental or offer for sale or for commercial rental any copy of the computer program

(c) No copyright except as provided in this Act, i.e., Copyright does not extend to any right beyond the scope of section 14.

Section 52: Certain acts not to be infringement of copyright.

(1) The following act shall not constitute an infringement of copyright, namely:

(a) …………

(aa) The making of copies or adaptation of a computer program by a lawful possessor of a copy of such computer program, from such copy —

a) In order to utilise the computer program for the purpose for which it was supplied; or

b) To make back-up copies purely as a tem-porary protection against loss, destruction or damage in order only to utilise the computer program for the purpose for which it was supplied.

IV. OECD on Software Payments

The 1992 OECD Model Convention (MC):

(1) Following a survey in the OECD member states, the question of classification of computer software was first considered in 1992 and accordingly revision made in the Commentary to the OECD Model Convention on Article 12.

(2) Software was generally defined as a program, or a series of program, containing instructions for a computer either for the computer itself or accomplishing other tasks. Modes of media transfer were also discussed.

(3) Acknowledged that OECD member countries typically protect software rights under copyright laws.

(4) Different ways of transfer of software rights e.g., Alienation of entire rights, alienation of partial rights (sale of a product subject to restrictions on the use).

The taxability was analysed under 3 situations:

First situation: Payments made where less than full rights in the software are transferred:

- In a partial transfer of rights the consideration is likely to represent a royalty only in very limited circumstances.

- One such case is where the transferor is the author of the software and alienates part of his right in favour of a third party to enable the latter to develop or exploit the software itself commercially — for example by development and distribution of it.

- In other cases, acquisition of the software will generally be for personal or business use of the purchaser and will be business income or independent personal services. The fact that software is protected by copyright or there are end use restrictions is of no relevance.

Second situation: Payments made for alienation of Complete Rights attached to the software:

- Payments made for transfer of a full ownership cannot result in royalty.

Difficulties can arise where there are extensive transfer of rights, but partial alienation of rights involving:

exclusive right of use during a specific period

or in a limited geographical area.

additional consideration related to usage.

consideration in the form of substantial lump-sum payment.

- Subject to facts, generally such payments are likely to be commercial income or capital gains rather than royalties.

Third situation: Software payments under mixed contracts:

- Examples include sale of computer hardware with built-in software with concessions of the right to use software with provision for services.

- In such a scenario, it was felt that the consideration be split on the basis of information contained in the contract or by a reasonable apportionment with the appropriate tax treatment being applicable to each part.

Thus for the first time these three situations were envisaged by the OECD in its 1992 MC.

2000 OECD MC brought in further refinements to the earlier positions.

It acknowledged that software can be transferred as an integral part of computer hardware or in independent form available for use with various hardware. For the first time, the 2000 MC suggested a distinction between a copyright in the program and software which incorporates a copy of the copyrighted program. The transferee’s rights will in most cases consist of partial rights or complete rights in the underlying copyright or they may be rights partial or complete in a copy of the program. — It does not matter, if such copy is provided in a material medium, or electronically. Payments made for acquisition of partial rights in the copyright will represent ‘royalty’ only if consideration is for granting of rights to use the program that would, without such licence, constitute an infringement of copyright.

The 2000 MC also throws light on rights to make multiple copies for operation within its own business and these are commonly referred to as ‘site licences’, ‘enterprise licences’, or ‘network licences’. If these are for the purposes of enabling the operation of the program on the licensee’s computers/network and reproduction for any other purpose is not permitted, payments for such arrangements would not be reckoned as royalty, but may be business profits.

2008 MC to the OECD Model expanded the scope of software payments by including transactions concerning digital products such as images, sounds or text. The downloading of images, sounds or text for the customers own use or enjoyment is not royalty as the payment is essentially for acquisition of data transmitted digitally. However, if the essential consideration for the payment for a digital product is the right to use that digital product, such as to acquire other types of contractual rights, data or services, then the same would be characterised as royalty.

Example a book publisher, who would download a picture and also acquire the right to reproduce that picture on the cover of a book that it is producing.

India’s position on OECD: India reserves its position on the interpretations provided in the OECD MC and is of the view that some of the payments referred therein may constitute royalties.

Issues in the controversy:

(1) Whether payment for purchase of computer software is payment for ‘goods’ or payment for ‘royalty’?

(2) Whether payment for computer software can be said to be payment for ‘use of process’ as referred to in clauses (i), (ii) and (iii) of the royalty definition in the Act?

(3) Whether payment for computer software is for ‘right to use the copyright in a program’ or ‘right to use the program only’? [Copyright v. Copyrighted Article]

(4) Whether mere grant of non-exclusive licence would fall within the ambit of ‘royalty’ definition under the Act? [Ref. clause (v) of the royalty definition in the Act which also includes the phrase ‘granting of a licences’]

(5) Whether payment for computer software can be said to ‘impart information concerning technical, industrial, commercial or scientific knowledge’ and hence falling under clause (iv) of the royalty definition under the Act?

(6) Section 115A prescribes the rate of tax applicable to a foreign company on income by way of ‘royalty’ or ‘fees to technical services’. Whether as per section 115A(1A) of the Act, it is not necessary that copyright therein should be specifically transferred as consideration in respect of any computer software is stated to be taxable u/s.115A?

V. Key judicial and advance rulings

CIT v. Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd., 64 DTR (Kar.) 178

Facts:

The assessee was engaged in the development and export of computer program. The assessee imported ‘shrinkwrapped’/‘off-the-shelf’ software from suppliers in foreign countries for use in its business and made payment for the same without deducting tax at source u/s.195.

Ruling of the High Court:

U/s.9(1)(vi) of the Act and Article 12 of the DTAA, “payments of any kind in consideration for the use of, or the right to use, any copyright of a literary, artistic or scientific work” is deemed to be ‘royalty’.

It is well settled that in the absence of any definition of ‘copyright’ in the Act or DTAA with the respective countries, reference is to be made to the respective law regarding definition of Copyright, namely, the Copyright Act, 1957, in India, wherein it is clearly stated that ‘literary work’ includes computer programs, tables and compilations including computer (databases).

On reading the contents of the respective agreement entered with the non-resident, it is clear that under the agreement, what is transferred is a right to use the copyright for internal business by making copies and back-up copies of the program.

The amount paid to the supplier for supply of the ‘shrinkwrapped’ software is not the price of the CD alone nor software alone nor the price of licence granted. It is a combination of all. In substance unless a licence was granted permitting the end-user to copy and download the software, the CD would not be helpful to the end-user.

There is a difference between a purchase of a book or a music CD, because while these can be used once they are purchased, software stored in a dumb CD requires a licence to enable the user to download it upon his hard disk, in the absence of which there would be an infringement of the owner’s copyright. Therefore, there is no similarity between the transaction of a computer program and books.

The decision of the Supreme Court in case of TCS v. State of AP, (271 ITR 404) distinguished as being in the context of sales tax.

Thus, held that the payments made in respect of computer program would constitute ‘royalty’ under the applicable DTAA and would also fall within the ambit of ‘royalty’ under the broader definition in the Act. Thus, the assessee would be required to deduct tax on the payment made in respect of computer programs.

Further, the Karnataka High Court in case of CIT v. M/s. Wipro Ltd., (ITA No. 2804 of 2005) has also held that payment for subscription/access to database is payment for licence to use the copyright hence taxable as ‘royalty’.

Director of Income-tax v. Ericsson Radio System AB, (ITA No. 504 of 2007) (Delhi High Court)

Facts:

The assessee, a Swedish company, entered into con-tracts with ten cellular operators for the supply of hardware equipment and software. The installation and testing were done in India by the assessee’s group entities.

The contracts were signed in India. The supply of the equipment was on CIF basis and the assessee took responsibility thereof till the goods reached India. The assessee claimed that the income arising from the said activity was not chargeable to tax in India.

The Assessing Officer and the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) held that the assessee had a ‘business connection’ in India u/s.9(1)(i) and a ‘permanent establishment’ under Article 5 of the DTAA. It was also held that the income from supply of software was assessable as ‘royalty’ u/s.9(1)(vi) and Article 13. On appeal, the matter was referred to Special Bench of the Tribunal. The Tribunal held that as the equipment had been transferred by the assessee offshore, the profits therefrom were not chargeable to tax. It also held that the profits from the supply of software were not assessable to tax as ‘royalty’ either under the Act or DTAA with Sweden.

Aggrieved by the common order of the Special Bench in case of Motorola Inc. 95 ITD 269 (Del.) (SB), which also covered the case of Ericsson, the Tax Authority filed an appeal before the High Court.

Ruling of the High Court:

The profits from the supply of equipment were not chargeable to tax in India because the property and risk in goods passed to the buyer outside India. The assessee had not performed installation service in India.

The argument that the software component of the supply should be assessed as ‘royalty’ is not acceptable because the software was an integral part of the GSM mobile telephone system and was used by the cellular operator for providing cellular services to its customers.

Software was embedded in the equipment and could not be independently used. It merely facilitated the functioning of the equipment and was an integral part thereof. The Tax Authority accepts that it could not be used independently. The fact that in the supply contract, the lump -sum price was bifurcated is not material. The same was only because differential customs duty was payable.

To qualify as royalty, it is necessary to establish that there is transfer of all or any right (including the granting of any licence) in respect of copy right of a literary, artistic or scientific work. Section 2(o) of the Copyright Act makes it clear that a computer program is to be regarded as a ‘literary work’. Thus, in order to treat the consideration paid by the cellular operator as royalty, it is to be established that the cellular operator, by making such payment, obtains all or any of the copyright rights of such literary work. In the present case, this has not been established. It is not even the case of the Revenue that any right contem-plated u/s.14 of the Copyright Act, 1957 stood vested in this cellular operator as a consequence of Article 20 of the supply contract.

A distinction has to be made between the acquisition of a ‘copyright right’ and a ‘copyrighted article’. The submissions made by the assessee on the basis of the OECD commentary are correct.

Even assuming the payment made by the cellular operator is regarded as a payment by way of royalty as defined in Explanation 2 below section 9(1)(vi), nevertheless, it can never be regarded as royalty within the meaning of the said term in Article 13, para 3 of the DTAA. This is so because the definition in the DTAA is narrower than the definition in the Act. Article 13(3) brings within the ambit of the definition of royalty a payment made for the use of or the right to use a copyright of a literary work. Therefore, what are contemplated are a payment that is dependent upon user of the copyright and not a lump-sum payment as is the position in the present case.

The payment received by the assessee was towards the title of the equipment of which software was an inseparable part incapable of independent use and it was a contract for supply of goods. Therefore, no part of the payment could be classified as payment towards royalty.

Solid Works Corporation, ITA No. 3219/Mum./2010 (Mum. Tribunal), dated 8-2-2012

Recently the Mumbai ITAT on the issue of characterisation of shrinkwrapped computer software in the case of Solid Works Corporation (Taxpayer) has held that the consideration received by the taxpayer for the shrinkwrapped software is not ‘royalty’ under the provisions of the India-USA DTAA, but business receipts.

While arriving at its decision, the ITAT relied on the favourable view taken by the Delhi High Court in the case of Ericsson, after considering the decision of the Karnataka High Court in the case of Samsung (supra).

It may be noted that the ITAT has also accepted the argument of the taxpayer that when two views are available, the one favourable to the taxpayer should be followed. This principle should apply even to a non-resident in view of the non-discrimination article in the DTAA.

This ruling should be helpful, especially to taxpayers coming within the jurisdiction of the Mumbai ITAT, and is likely to have persuasive value in case of other neutral jurisdictions (i.e., other than the jurisdiction of the Karnataka High Court), in defending the tax position that is taken based on whether a transaction is a ‘copyright right’ or a ‘copyrighted article’.

Further, the Mumbai Tribunal in the following cases had ruled the issue in favour of the taxpayer by following the Special Bench decision in case of Motorola Inc.:

- Kansai Nerolac Paints Ltd. v. Addl. DIT, 134 TTJ 342 (Mum.)

- DDIT v. M/s. Reliance Industries Ltd., 43 SOT 506 (Mum.)

- Addl. DIT v. Tata Communications Limited, 2010 TII 157 ITAT-Mum.

Controversy before the AAR:

The Authority for Advance Rulings (‘AAR’) recently in its ruling in the case of Citrix Systems Asia Pacific Pty. Limited (AAR No. 882 of 2009) and Millennium IT Software Ltd., 338 ITR 391 had an occasion to deal with the aforesaid issue under consideration, wherein the AAR while deciding against the taxpayer’s contention, held that the income from the transaction be regarded as a royalty, liable to tax in India. In deciding the issue in this case the AAR gave findings that were contrary to its own findings on the subject given in the earlier decisions in the cases of Dassault Systems K. K., 322 ITR 125 and FactSet Research Systems Inc., 317 ITR 169.

Citrix Systems Asia Pacific Pty. Limited (AAR):

In this case, the AAR held that the payment received from Indian distributor under software distribution agreement is taxable as royalty u/s.9(1)(vi) of the Act as well as Article 12 of the India-Australia DTAA. It also observed that sale/licence to use software entails transfer of rights in copyrights embedded in software. The AAR took a contrary view to its earlier ruling in the case of Dassault Systems and refused to rely on the Delhi HC ruling in the case of Ericsson (supra), thereby following the ruling in the case of Millennium IT Software and the Karnataka HC in the case of Samsung (supra).

It is interesting to note that the Chairman of the AAR has mentioned in the ruling of Citrix that the differing views on the issue can get resolved and the matter can be set at rest only by a decision of the Supreme Court, laying down the law finally, to be followed by all the Courts and Tribunals including the AAR. Only an authoritative pronouncement by the Apex Court can settle this controversy.

Millennium IT Software’s case:

In this ruling, the AAR held that the licence fees paid for use of ‘Licenced Program’ is taxable as ‘royalty’ under clause (v) of Explanation 2 to section 9(1)(vi) of the Act and Article 12 of the India-Sri Lanka DTAA. Thus the provisions of withholding tax u/s.195 are applicable to the applicant. The AAR’s ruling was based on the ruling of the Delhi ITAT in the case of Gracemac Corporation v. DIT, (42 SOT 550).

The said Delhi ITAT ruling has been distinguished by the Mumbai ITAT in the case of TII Team Telecom Inter-national Pvt. Ltd., 60 DTR 177. Also, the Mumbai ITAT has distinguished the AAR ruling of Millennium in the case of Novel Inc. (ITA No. 4368/Mum./2010) where income of non-resident from re-selling of software via Indian distributor was held as not taxable.

Conclusion:

The issue under consideration is otherwise a multi-faceted issue and has several dimensions which are sought to be addressed through a few questions and answers thereon. An analysis of the above-discussed important decisions rendered in the context of software/ use of technology-related payments give rise to the following open-ended questions before the taxpayers:

- What is meant by the expression ‘transfer of all or any rights (including granting of licence) and which rights are sought to be covered?

- Whether the rights referred in section 14 of the Copyrights Act, 1957 are transferred in sale of computer software to end-users?

- Whether ‘computer program’ is copyright and/or industrial intellectual property?

- Whether the payment made in relation to shrink-wrapped/off-the-shelf software would constitute payment for a copyright, would need to be determined as per section 14 of the Copyright Act, 1957?

- Where there is any distinction between a copyright v. copyrighted article in light of the decision of the Karnataka High Court in the case of Samsung Electronics?

- Whether in case of bundled contract i.e., software supplied along with hardware, any bifurcation can be made between the payments made for software and hardware?

- Whether every payment made by the taxpayer for use of computer program would constitute ‘royalty’ under the Act and relevant DTAA?

- Is the position under the DTAA stronger than un-der the Act as the definition of royalty under the DTAA is restrictive than under the Act?

- What would be the position, where the DTAA between two Contracting States specifically cover the payments for computer software program within the ambit of taxation as royalty, vis-à-vis the DTAA where such inclusion is not there.

Key takeaways:

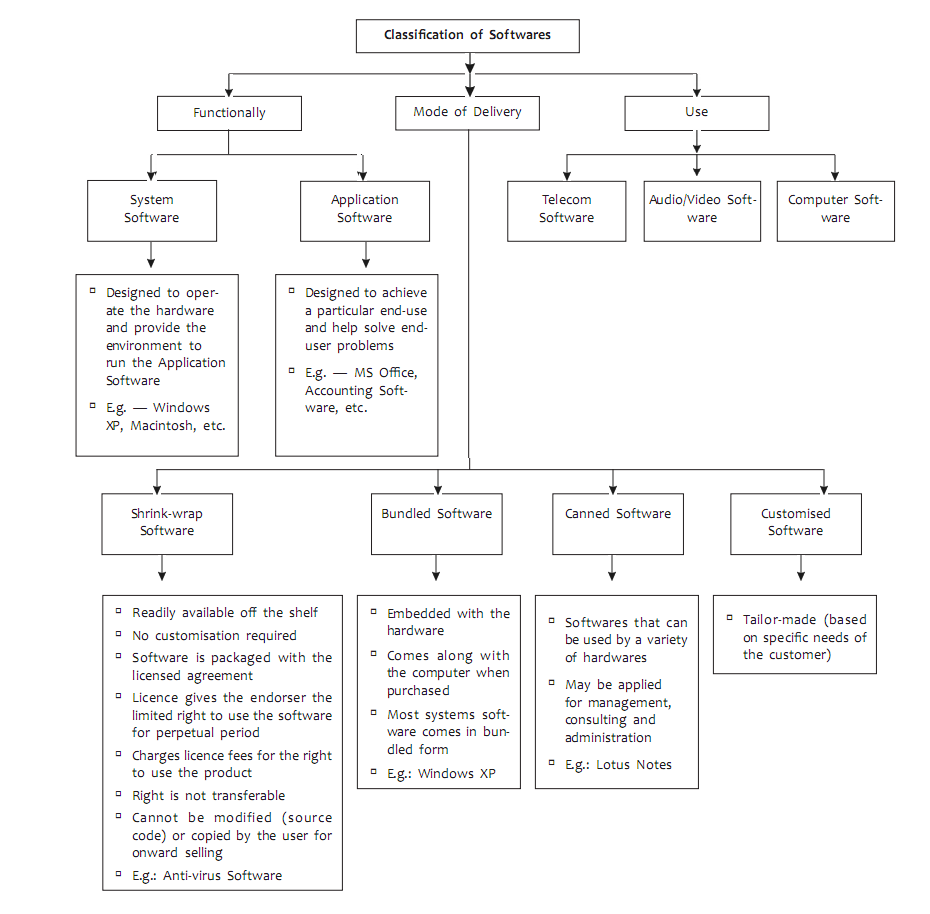

The ruling of the Karnataka High Court in the case of Samsung would have significant tax implications on the industries operating under jurisdiction of the Karnataka High Court dealing in computer software/ other technology. The Delhi High Court in the case of Ericsson Radio System A.B., New Delhi having upheld the decision of the Special Bench on this issue, could help the taxpayers to reinforce its position on this contentious issue before various Tribunals (except Bangalore Tribunal). Although, the AAR rulings in the case of Dassault, Geo quest, Citrix’s and Millennium are applicable only to the applicant and Tax Department, they have persuasive value.

Analysis of Finance Bill, 2012 — Proposals:

Controversy revolving around the tax-ability of software payments, is sought to be resolved by amendment to section 9(1)(vi) of the Act. The Finance Bill, 2012 has proposed to insert Explanation 4 and Explanation 5 to the section 9(1)(vi) with retrospective effect from 1st June 1976. The definition of the royalty in Explanation 2 is sought to be expanded by these two explanations.

Explanation 4 clarifies that the transfer of all or any rights in respect of any right, property or information includes transfer of all or any right for use or right to use a computer software (including granting of a licence), irrespective of the medium through which such right is transferred.

Implications of Explanation 4:

By insertion of proposed Explanation 4 to section 9(1) (vi) the controversy surrounding taxability of software payment by characterising it as royalty is sought to be put at rest. The main issue would be whether by inserting Explaination and expanding the scope of the definition ‘royality’ by way of clarificatory retro-spective amendment, can a payment for software be brought to tax?

The dispute was whether by making a payment for software, the licensee gets rights in the ‘copyright’ of the software. It appears that it is felt by the law-makers that by specifically inserting payment for software itself in the definition of royalty, this purpose will be achieved. The moot question however is, whether it can be done retrospectively from 1 June 1976?

Further, Explanation 5 clarifies that royalty includes consideration in respect of any right, property or information whether or not the payer has the possession or control of it, the payer is using it directly or such right, etc. are located outside India.

Implications of Explanation 5:

Explanation 5 seeks to clarify that once a right, property or information is deemed to be covered under Explanation 2 read with Explanation 4 to the section 9(1)(vi), the interpretation would continue to remain so, irrespective of possession or control of the right, property or information, direct or indirect use of the right, property or information or location of the right, property or information.

While it remains to be seen how Explanation 5 will be interpreted by the Courts. It would not be correct to say that on fulfilment of the situations laid down in Explanation 5, the taxability of sale of software is, per se, attracted.

Existence of beneficial treaty provisions:

As mentioned above, the payment for the sale or licence of software, would now get covered u/s. 9(1) (vi), if provisions of the Act are to be applied. However, if the provisions of the treaty are beneficial than the provisions of section 9(1)(vi), still it will be possible to contend that payment for software as per the provisions of the treaty is not liable to tax in India. Further, out of several treaties signed by India, only in 4 to 5 treaties, namely, Morocco, Rus-sia, Turkmenistan, Malaysia and Tobago specifically payment for software is covered as part of royalty. Therefore, it will still be a good case to argue that in case of, off-the-shelf or standardised software are not chargeable to tax in India except where as per treaty it is specifically covered.

It is, therefore, important to note here that the taxpayers who are entitled to claim benefit of tax treaty will still be able to take shelter under the beneficial treaty provisions as the scope of provisions (generally Article 12) under the treaty is restricted than under the Act.

Way forward:

- It is learnt that the taxpayer has filed an SLP against the Karnataka High Court ruling in the case of Samsung Electronics Company Ltd. in December 2011 which is yet to be admitted. The SC has reacted that adjudication on this issue is going to be the next big thing after Vodafone judgment.

- The proposed amendment, as mentioned above, may resolve the controversy in respect of future transactions, however, whether the amendment will apply retrospectively or not will be a matter of debate and litigation. So in cases where applicable the treaty does not specifically cover the software, the non-taxability could be claimed.

- Hence, till the time, the issue gets settled at the highest level, litigation over taxability of software payments is likely to continue. So let’s WAIT & WATCH.

| Year of |

Decision in the case of |

Authority |

Jurisdiction |

Favourable |

Against |

| judgment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2004 |

Tata Consultancy Services |

Supreme |

— |

3 |

|

|

|

Court |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2004 |

Wipro Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2005 |

Motorola Inc. |

Special |

Delhi |

3 |

|

|

|

Bench ITAT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2005 |

Lucent Technologies Hindustan Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2005 |

Samsung Electronics Company Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2005 |

Sonata Software Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2006 |

Hewlett-Packard (India) (P) Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2006 |

Sonata Information Technology Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2006 |

IMT Labs (India) Pvt. Ltd. |

AAR |

— |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2006 |

Metapath Software International Ltd. |

ITAT |

Delhi |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2008 |

Airports Authority of India |

AAR |

— |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2009 |

FactSet Research Systems Inc. |

AAR |

— |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2009 |

Samsung Electronics |

High Court |

Karnataka |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Lotus Development (Asia Pacific) Ltd. Corp. |

ITAT |

Delhi |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Microsoft Corporation and |

|

|

|

|

|

Gracemac Corporation |

ITAT |

Delhi |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Reliance Industries Ltd. |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

M/s. Tata Communications Ltd. |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

M/s. Daimler Chrysler AG |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Dassault Systems K.K. |

AAR |

— |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Year of |

Decision in the case of |

Authority |

Jurisdiction |

Favourable |

Against |

| judgment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

GeoQuest Systems BV |

AAR |

— |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Velankani Mauritius Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Kansai Nerolac Paints Ltd. |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

Bharati AXA General Insurance Co. Ltd. |

AAR |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Asia Satellite Co. Ltd. |

High Court |

Delhi |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Dynamic Vertical Software India Pvt. Ltd. |

High Court |

Delhi |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Standard Chartered Bank Ltd. |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

ING Vysya Bank Ltd. |

ITAT |

Bangalore |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

TII Telecom International Pvt. Ltd. |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

M/s. Abaqus Engineering Pvt. Ltd. |

ITAT |

Chennai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Millennium IT Software |

AAR |

— |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Samsung Engineering Company Limited |

High Court |

Karnataka |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Novel Inc. (Mum.) |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Lucent Technologies |

High Court |

Karnataka |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

Ericsson Radio System AB |

High Court |

Delhi |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2012 |

Solid Works Corporation |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2012 |

Citrix Systems Asia Pacific Pty. Limited |

AAR |

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2012 |

Acclerys K. K. |

AAR |

— |

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2012 |

People Interactive (I) P. Ltd. |

ITAT |

Mumbai |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|