There are various options available to a country while formulating its tax laws for taxation of dividends. In the past India was following the DDT system of taxing dividends. From A.Y. 2021-22 India has moved to the classical system of taxing dividends. Under the classical system of taxation, the company is first taxed on its profits and then the shareholders are taxed on the dividends paid by the company.

2.1 Definition of the term ‘dividend’

The term ‘dividend’ has been defined in section 2(22) of the Income-tax Act, 1961. It includes the following payments / distributions by a company, to the extent it possesses accumulated profits:

a. Distribution of assets to shareholders;

b. Distribution of debentures to equity shareholders or bonus shares to preference shareholders;

c. Distribution to shareholders on liquidation;

d. Distribution to shareholders on capital reduction;

e. Loan or advance given to shareholder or any concern controlled by a shareholder.

The domestic tax definition of dividend as compared to the definition under the DTAA has been analysed subsequently in this article.

2.2 Outbound dividends

Dividend paid by an Indian company is deemed to accrue or arise in India by virtue of section 9(1)(iv).

Section 8 provides for the period when the dividend would be added to the income of the shareholder assessee. It provides that the interim dividend shall be considered as income in the year in which it is unconditionally made available to the shareholder and that the final dividend shall be considered as income in the year in which it is declared, distributed or paid.

The timing of the taxation of interim dividend as per the Act, i.e., when it is made unconditionally or at the disposal of the shareholder, is similar to that provided in the description of the term ‘paid’ above. However, the timing of the taxation of the final dividend may not necessarily match with that of the description of the term.

For example, in case of final dividend declared by an Indian company to a company resident of State X in September, 2020 but paid in April, 2021, when would such dividends be taxed as per the Act?

In this regard, it may be highlighted that the source rule for taxation of dividends ‘paid’ by domestic companies to non-residents is payment as per section 9(1)(iv) and not declaration of dividend. The Bombay High Court in the case of Pfizer Corpn. vs. Commissioner of Income-tax (259 ITR 391) held that,

‘….but for 9(1)(iv) payment of dividend to non-resident outside India would not have come within 5(2)(b). Therefore, 9(1)(iv) is an extension to 5(2)(b)……. in case where the question arises of taxing income one has to consider place of accrual of the dividend income. To cover a situation where dividend is declared in India and paid to non-resident out of India, 5(2)(b) has to be read with 9(1)(iv). Under 9(1)(iv), it is clearly stipulated that a dividend paid by an Indian company outside India will constitute income deemed to (be) accruing in India on effecting such payment. In 9(1)(iv), the words used are “a dividend paid by an Indian company outside India”. This is in contradiction to 8 which refers to a dividend declared, distributed or paid by a company. The word “declared or distributed” occurring in 8 does not find place in 9(1)(iv). Therefore, it is clear that dividend paid to non-resident outside India is deemed to accrue in India only on payment.’

Therefore, one can contend that dividend declared by an Indian company would be considered as income in the hands of the non-resident shareholder only on payment.

Earlier, dividends declared by an Indian company were subject to DDT u/s 115O payable by the company declaring such dividends. The rate of DDT was 15% and in case of deemed dividend the DDT rate from A.Y. 2019-20 (up to A.Y. 2020-21) was 30%. Further, section 115BBDA, referred to as the super-rich tax on dividends, taxed a resident [other than a domestic company, an institution u/s 10(23C) or a charitable trust registered u/s 12A or section 12AA] earning dividends (from Indian companies) in excess of INR 10 lakhs. In case of such a resident, the dividend in excess of INR 10 lakhs was taxed at the rate of 10%.

From A.Y. 2021-22, dividends paid by an Indian company to a non-resident are taxed at the rate of 20% (plus applicable surcharge and education cess). Further, with the dividend now being taxed directly in the hands of the shareholders, section 115BBDA is now inoperable.

Payment of dividend to non-residents or to foreign companies would require deduction of tax at source u/s 195 at the rates in force on the sum chargeable to tax. The rates in force in respect of dividends for non-residents or foreign companies as discussed above is 20% (plus applicable surcharge or education cess) or the rate as per the relevant DTAA (subject to fulfilment of conditions in respect of treaty eligibility), whichever is more beneficial.

2.3 Inbound dividends

Dividends paid by foreign companies to Indian companies which hold 26% or more of the capital of the foreign company are taxable at the rate of 15% u/s 115BBD. Further, such dividends, when distributed by the Indian holding company to its shareholders, were not included while computing the dividend distribution tax payable u/s 115O. However, section 80M also provides such a pass-through status to the dividends received to the extent the said dividends received by an Indian company have been further distributed as dividend within one month of the date of filing the return of income of the Indian company. The tax payable would be further reduced by the tax credit, if any, paid by the recipient in any country.

Let us take an example, say F Co, a foreign company in country A distributes dividend of 100 to I Co, an Indian company which further distributes 30 as dividend to its shareholders (within the prescribed limit). Assuming that the withholding tax on dividends in country A is 10, the amount of tax payable would be computed as below:

|

|

Particulars

|

Amount

|

|

A

|

Dividend received from F Co

|

100

|

|

B

|

(-) Deduction u/s 80M for dividends distributed by I Co

|

(30)

|

|

C

|

Dividend liable to tax (A-B)

|

70

|

|

D

|

Tax u/s 115BBD (C * 15%)

|

10.5

|

|

E

|

(-) Tax credit for tax paid in country A (assuming full tax

credit available)

|

(10)

|

|

F

|

Net tax payable (D-E) (plus applicable surcharge

and education cess)

|

0.5

|

Dividends received by other taxpayers are taxable at the applicable rate of tax (depending on the type of person receiving the dividends).

2.4 Taxation in case the Place of Effective Management (‘POEM’) of foreign company is in India

a. Dividend paid by foreign company having POEM in India to non-resident shareholder

As highlighted earlier, section 9(1)(iv) deems income paid by an Indian company to accrue or arise in India. In the present case, as the deeming fiction only refers to dividend paid by an Indian company, one may be able to take a position that the deeming fiction should not be extended to apply to foreign companies even if such foreign companies are resident in India due to the POEM of such companies in India. One may be able to argue that if the Legislature wanted such dividend to be covered, it would have specifically provided for it as done in respect of the existing source rules for royalty and fees for technical services in section 9, wherein a payment by a non-resident would deem such income to accrue or arise in India. Accordingly, the dividend paid by the foreign company to a non-resident shareholder may not be taxable in India even though the foreign company, declaring such dividend, is considered as a resident of India due to the POEM of the foreign company in India.

b. Dividend paid by foreign company having a POEM in India to resident shareholder

Such dividend would be taxed in India on account of the recipient of the dividend being a resident of India. Further, section 115BBD provides a lower rate of tax on dividends paid by a foreign company to an Indian company, subject to the Indian company holding at least 26% in nominal value of the equity share capital of the foreign company. Accordingly, such lower rate of tax would apply to dividends received by an Indian company from a foreign company (subject to the fulfilment of the minimum holding requirement) even if such foreign company is considered as a resident in India on account of its POEM being in India.

c. Dividend received by a foreign company

The provisions of section 115A apply in the case of receipt by a non-resident (other than a company) and a foreign company. Accordingly, dividend received by a foreign company would be taxed at the rate of 20% (plus applicable surcharge and education cess) even if the foreign company is considered as a tax resident of India on account of its POEM being in India.

3. ARTICLE 10 OF THE UN MODEL CONVENTION OR DTAAs DEALING WITH DIVIDENDS

As discussed above, dividends typically give rise to economic double taxation. However, the dividends may also be subject to juridical double taxation in a situation where the income, i.e., dividend is taxed in the hands of the same shareholder in two different jurisdictions. Article 10 of a DTAA typically provides relief from such juridical double taxation.

Article 10 dealing with taxation of dividends is typically worded in the following format:

a. Para 1 deals with the bilateral scope for the applicability of the Article;

b. Para 2 deals with the taxing right of the State of source to tax such dividends and the restrictions for such State in taxing the dividends;

c. Para 3 deals with the definition of dividends as per the DTAA or Model Convention;

d. Para 4 deals with dividends paid to a company having a PE in the other State;

e. Para 5 deals with prohibition of extra-territorial taxation on dividends.

4. ARTICLE 10(1) OF THE UN MODEL CONVENTION OR DTAAs

Article 10(1) of a DTAA typically provides the source rule for dividends under the DTAA and also provides the bilateral scope for which the Article applies.

Article 10(1) of the UN Model (2017) reads as under: ‘Dividends paid by a company which is a resident of a Contracting State to a resident of the other Contracting State may be taxed in that other State.’

4.1. Bilateral scope

Paragraph 1 deals with the bilateral scope for applicability of the Article. In other words, for Article 10 to apply the company paying the dividends should be a resident of one of the Contracting States and the recipient of the dividends should be a resident of the other Contracting State.

4.2. Source rule

Paragraph 1 also provides the source rule for the dividends, which helps in identifying the State of source for the Article. The paragraph is applicable to dividends ‘paid by a company which is a resident of a Contracting State’. Therefore, the State of source in the case of dividends shall be the State in which the company paying the dividends is a resident.

4.3. The term ‘paid’

Article 10 provides for allocation of taxing rights of dividends paid by a company. Therefore, it is important to understand the meaning of the term ‘paid’.

The description of the term in the OECD Commentary is as follows, ‘The term “paid” has a very wide meaning, since the concept of payment means the fulfilment of the obligation to put funds at the disposal of the shareholder in the manner required by contract or by custom.’

The issue of ‘paid’ is extremely relevant in the case of a deemed dividend u/s 2(22).

Section 2(22)(e) provides that the following payments by a company, to the extent of its accumulated profits, shall be deemed to be dividends under the Act:

a. Advance or loan to a shareholder who holds at least 10% of the voting power in the payee company;

b. Advance or loan to a concern in which the shareholder is a member or partner and holds substantial interest (at least 20%) in the recipient concern.

While a loan or advance to a shareholder, constituting deemed dividend u/s 2(22)(e), would constitute dividend ‘paid’ to the shareholder and, therefore, covered under Article 10(1) (subject to the issue as to whether deemed dividend constitutes dividend for the purposes of the DTAA, discussed in subsequent paragraphs), the question arises whether, in case of advance or loan given to a concern in which the shareholder has substantial interest, would be considered as ‘dividend paid by a company’.

Let us take the following example. Hold Co, a company resident in Singapore has two wholly-owned subsidiaries in India, I Co1 and I Co2. During the year, I Co1 grants a loan to I Co2. Assuming that neither I Co1 nor I Co2 is in the business of lending money, the loan given by I Co1 to I Co2 would be considered as deemed dividend.

The Delhi High Court in the case of CIT vs. Ankitech (P) Ltd. & Ors. (2012) (340 ITR 14) held that while section 2(22)(e) deems a loan to be dividend, it does not deem the recipient to be a shareholder. This view was upheld by the Supreme Court in the case of CIT vs. Madhur Housing & Development Co. & Ors. (2018) (401 ITR 152).

Therefore, the deemed dividend would be taxed in the hands of the shareholder, i.e., Hold Co in this case, and not I Co2, being the recipient of the loan, as I Co2 is not a shareholder. Would the dividend then be considered to be ‘paid’ to Hold Co as the funds have actually moved from I Co1 to I Co2 and Hold Co has not received any funds?

The question to be answered here is how does one interpret the term ‘paid’? In this context, Prof. Klaus Vogel in his book, ‘Klaus Vogel on Double Tax Conventions’ (2015 4th Edition), suggests,

‘“Payment” cannot depend on the transfer of money or “monetary funds”, nor does it depend on the existence of a clearly defined “obligation” of the company to put funds at the disposal of the shareholder; instead, in order to achieve consistency throughout the Article, it has to be construed so as to cover all types of advantages being provided to the shareholder covered by the definition of “dividends” in Article 10(3) OECD and UN MC, which include “benefits in money or money’s worth”. It has been argued that the term “payment” requires actual benefits to be provided to the shareholder, so that notional dividends would automatically fall outside the scope of Article 10 OECD and UN MC. This view has to be rejected, however, in light of the need for internal consistency of the provisions of the OECD and UN MC, which rather suggests that the terms “paid to”, “received by” and “derived from” serve only the purpose to connect income that is dealt with in a certain Article to a certain taxpayer, so that any income that falls within the definition of a “dividend” of Article 10(3) OECD and UN MC needs to be considered to be so “paid”. Indeed, it would make little sense to define a “dividend” with reference to domestic law of the Source State only to prohibit taxation of certain such “dividends” because they have not actually been “paid”.’

Accordingly, one may take a view that in such a scenario dividend would be considered as ‘paid’ under the DTAA.

4.4. The term ‘may be taxed’

The paragraph provides that the dividend ‘may be taxed’ in the State of residence of the recipient of the dividends. It does not provide an exclusive right of taxation to the State of residence.

The interpretation of the term ‘may be taxed’ still continues to be a vexed issue to a certain extent even after the CBDT Notification No. 91 of 2008 dated 28th August, 2008. This controversy would be covered by the authors in a subsequent article.

5. ARTICLE 10(2) OF THE UN MODEL CONVENTION OR DTAAs

Article 10(2) of a DTAA typically provides the taxing right of the State of source for dividends under the DTAA.

Article 10(2) of the UN Model (2017) reads as under:

‘However, such dividends may also be taxed in the Contracting State of which the company paying the dividends is a resident and according to the laws of that State, but if the beneficial owner of the dividends is a resident of the other Contracting State, the tax so charged shall not exceed:

a. __ per cent of the gross amount of the dividends if the beneficial owner is a company (other than a partnership) which holds directly at least 25 per cent of the capital of the company paying the dividends throughout a 365-day period that includes the day of the payment of the dividend (for the purpose of computing that period, no account shall be taken of changes of ownership that would directly result from a corporate reorganisation, such as a merger or divisive reorganisation, of the company that holds the shares or pays the dividend);

b. __ per cent of the gross amount of the dividends in all other cases.

The competent authorities of the Contracting States shall by mutual agreement settle the mode of application of these limitations.

This paragraph shall not affect the taxation of the company in respect of the profits out of which the dividends are paid.’

While the UN Model does not provide the rate of tax for paragraphs 2(a) and 2(b) and leaves the same to the individual countries to decide at the time of negotiating a DTAA, the OECD Model provides for 5% in sub-paragraph (a) and 15% in sub-paragraph (b).

5.1. Right of taxation to the source State

Paragraph 2 provides the right of taxation of dividends to the source State, i.e., the State in which the company paying the dividends is a resident. The first part provides the right of taxation to the source State and the second part of the paragraph restricts the right of taxation of the source State to a certain percentage on the applicability of certain conditions.

5.2. The term ‘may also be taxed’

Paragraph 2 provides that dividends paid by a company may also be taxed in the State in which the company paying the dividends is a resident.

5.3. Beneficial owner

The benefit of the lower rate of tax in the source State is available only if the beneficial owner is a resident of the Contracting State. Therefore, if the beneficial owner is not a resident of the Contracting State, the second part of the paragraph would not apply and there would be no restriction on the source State to tax the dividends.

The beneficial ownership test is an anti-avoidance provision in the DTAAs and was first introduced in the 1966 Protocol to the 1945 US-UK DTAA. The concept of beneficial ownership was first introduced by the OECD in its 1977 Model Convention. However, the Model Commentary did not explain the term until the 2010 update.

The term ‘beneficial owner’ has not been defined in the DTAAs or the Model Conventions.

However, the OECD Model Commentary explains the term ‘beneficial owner’ to mean a person who, in substance, has a right to use and enjoy the dividend unconstrained by any contractual or legal obligation to pass on the said dividend to another person.

In the case of X Ltd., In Re (1996) 220 ITR 377, the AAR held that a British bank was the beneficial owner of the dividends paid by an Indian company even though the shares of the Indian company were held by two Mauritian entities which were wholly-owned subsidiaries of the British bank. However, the AAR did not dwell on the term beneficial owner but stressed on the fact that

the Mauritian entities were wholly-owned by the British bank.

Some of the key international judgments in this regard are those of the Canadian Tax Court in the cases of Prevost Car Inc. vs. Her Majesty the Queen (2009) (10 ITLR 736) and Velcro Canada vs. The Queen (2012) (2012 TCC 57) and of the Court of Appeal in the UK in the case of Indofood International Finance Ltd. vs. JP Morgan Chase Bank NA (2006) (STC 1195).

In the case of JC Bamford Investments vs. DDIT (150 ITD 209), the Delhi ITAT held (in the context of royalty) that the ‘beneficial owner’ is he who is free to decide (i) whether or not the capital or other assets should be used or made available for use by others, or (ii) on how the yields therefore should be used, or (iii) both.

Similarly, the Mumbai Tribunal in the case of HSBC Bank (Mauritius) Ltd. v. DCIT (International Taxation) (2017) (186 TTJ 619) has explained the term ‘beneficial owner’, in the context of interest as, ‘“Beneficial owner” can be one with full right and privilege to benefit directly from the interest income earned by the bank. Income must be attributable to the assessee for tax purposes and the same should not be aimed at transmitting to the third parties under any contractual agreement / understanding. Bank should not act as a conduit for any person, who in fact receives the benefits of the interest income concerned.’

The question that arises is, how does one practically evaluate whether the recipient is a beneficial owner of the dividends? In this case, generally, dividends are paid to group entities wherein it is possible for the Indian company paying the dividends to evaluate whether or not the shareholder is merely a conduit. A Chartered Accountant certifying the taxation of the dividends in Form 15CB can ask for certain information such as financials of the non-resident shareholder in order to evaluate whether the recipient shareholder is a conduit company, or whether such shareholder has substance. In the absence of such information or such other documentation to substantiate that the shareholder is not a conduit company, it is advisable that the benefit under the DTAA is not given. It is important to highlight that an entity, even though a wholly-owned subsidiary, can be considered as a beneficial owner of the income if it can substantiate that it is capable of and is undertaking decisions in respect of the application of the said income.

6. ARTICLE 10(3) OF THE UN MODEL CONVENTION AND DTAAs

Article 10(3) of a DTAA generally provides the definition of dividends.

Article 10(3) of the UN Model (2017) reads as under: ‘The term “dividends” as used in this Article means income from shares, “jouissance” shares or “jouissance” rights, mining shares, founders’ shares or other rights, not being debt claims, participating in profits, as well as income from other corporate rights which is subjected to the same taxation treatment as income from shares by the laws of the State of which the company making the distribution is a resident.’

Therefore, the term ‘dividends’ includes the income from the following:

a. Shares, jouissance shares or jouissance rights, mining shares, founders’ shares;

b. Other rights, not being debt claims, participating in profits;

c. Income from corporate rights subjected to the same tax treatment as income from shares in the source State.

6.1 Inclusive definition

The definition of the term ‘dividends’ in the DTAA as well as the OECD and UN Model is an inclusive definition. Further, it also gives reference to the definition of the term in the domestic law of the source State. The reason for providing an inclusive definition is to include all the types of distribution by the company to its shareholders.

6.2 Meaning of various types of shares and rights

The various types of shares referred to in the definition above are not relevant under the Indian corporate laws and, therefore, have not been further analysed.

6.3 Deemed dividend

The OECD Commentary provides that the term ‘dividends’ is expansively defined to include not only distribution of profits but even disguised distributions. However, the question that arises is whether such deemed dividend would fall under any of the limbs of the definition of dividends in the Article.

The Mumbai ITAT in the case of KIIC Investment Company vs. DCIT (2018) (TS – 708 – ITAT – 2018) while evaluating whether deemed dividend would be covered under Article 10(4) of the India-Mauritius DTAA (having similar language to the UN Model), held,

‘The India-Mauritius Tax Treaty prescribes that dividend paid by a company which is resident of a contracting state to a resident of other contracting state may be taxed in that other state. Article 10(4) of the Treaty explains the term “dividend” as used in the Article. Essentially, the expression “dividend” seeks to cover three different facets of income; firstly, income from shares, i.e. dividend per se; secondly, income from other rights, not being debt claims, participating in profits; and, thirdly, income from corporate rights which is subjected to same taxation treatment as income from shares by the laws of contracting state of which the company making the distribution is a resident. In the context of the controversy before us, i.e. ‘deemed dividend’ under section 2(22)(e) of the Act, obviously the same is not covered by the first two facets of the expression “dividend” in Article 10(4) of the Treaty. So, however, the third facet stated in Article 10(4) of the Treaty, in our view, clearly suggests that even “deemed dividend” as per Sec. 2(22)(e) of the Act is to be understood to be a “dividend” for the purpose of the Treaty. The presence of the expression “same taxation treatment as income from shares” in the country of distributor of dividend in Article 10(4) of the Treaty in the context of the third facet clearly leads to the inference that so long as the Indian tax laws consider “deemed dividend” also as “dividend”, then the same is also to be understood as “dividend” for the purpose of the Treaty.’

Therefore, without dwelling on the issue as to whether deemed dividend can be considered as income from corporate rights, the Mumbai ITAT held that deemed dividend would be considered as dividend under Article 10 of the DTAA.

In this regard it may be highlighted that the last limb of the definition of the term in the India-UK DTAA does not include the requirement of the income from corporate rights and therefore is more open-ended than the OECD Model. It reads as follows, ‘…as well as any other item which is subjected to the same taxation treatment as income from shares by the laws …’

7. ARTICLE 10(4) OF THE UN MODEL CONVENTION AND DTAAs

Article 10(4) of a DTAA provides for the tax position in case the recipient of the dividends has a PE in the other Contracting State of which the company paying the dividends is resident.

Article 10(4) of the UN Model (2017) reads as under, ‘The provisions of paragraphs 1 and 2 shall not apply if the beneficial owner of the dividends, being a resident of a Contracting State, carries on business in the other Contracting State of which the company paying the dividends is a resident, through a permanent establishment situated therein, or performs in that other State independent personal services from a fixed base situated therein, and the holding in respect of which the dividends are paid is effectively connected with such permanent establishment or fixed base. In such case the provisions of Article 7 or Article 14, as the case may be, shall apply.’

The difference between the OECD Model and the UN Model is that the OECD Model does not provide reference to Article 14 as the Article dealing with Independent Personal Services is deleted in the OECD Model.

7.1 Need to tax under Article 7 or Article 14

The paragraph states that once the bilateral scope in Article 10(1) is met, if the beneficial owner of the dividends has a PE in the source State and the holding in respect of which the dividends are paid is effectively connected to such PE, then the provisions of Article 7 or Article 14 shall override the provisions of Article 10.

To illustrate, A Co, resident of State A, has a subsidiary, B Co, as well as a branch (considered as a PE in this example) in State B. If the holding of B Co is effectively connected to the branch of A Co in State B, Article 7 of the A-B DTAA would apply and not Article 10.

The reason for the insertion of this paragraph is that once a taxpayer has a PE in the source State and the dividends are effectively connected to such PE, they would be included in the profits attributable to the PE and taxed as such in accordance with Article 7 of the DTAA. Therefore, taxing the same dividends on a gross basis under Article 10 and on net basis under Article 7 would lead to unnecessary complications in State B. In order to alleviate such unnecessary complications, it is provided that the dividends would be included in the net profits attributable to the PE and taxed in accordance with Article 7 and not Article 10.

7.2 The term ‘effectively connected’

The OECD Model Commentary provides a broad

guidance as to when the holdings would be considered as being ‘effectively connected’ to a PE and provides the following circumstances in which it would be considered so:

a. The economic ownership of the holding is with the PE;

b. Under the separate entity approach, the benefits as well as the burdens of the holding (such as right to the dividends attributable to ownership, potential exposure of gains and losses from the appreciation and depreciation of the holding) is with the PE.

8. ARTICLE 10(5) OF THE UN MODEL CONVENTION AND DTAAs

Article 10(5) of a DTAA deals with prevention of extra-territorial taxation.

Article 10(5) of the UN Model (2017) reads as under, ‘Where a company which is a resident of a Contracting State derives profits or income from the other Contracting State, that other State may not impose any tax on the dividends paid by the company, except insofar as such dividends are paid to a resident of that other State or insofar as the holding in respect of which the dividends are paid is effectively connected with a permanent establishment or a fixed base situated in that other State, nor subject the company’s undistributed profits to a tax on the company’s undistributed profits, even if the dividends paid or the undistributed profits consist wholly or partly of profits or income arising in such other State.’

Each country is free to draft source rules in its domestic tax law as it deems fit. Paragraph 5, therefore, prevents a country from taxing dividends paid by a company to another, simply because the dividend is in respect of profits earned in that country, except in the following circumstances:

a. The company paying the dividends is a resident of that State;

b. The dividends are paid to a resident of that State; and

c. The holding in respect of which the dividends are paid is effectively connected to the PE of the recipient in that State.

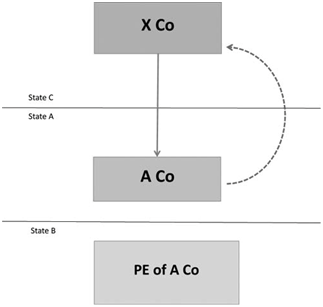

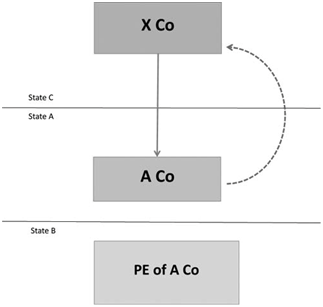

Let us take an example where A Co, a resident of State A, earns certain income in State B and out of

the profits from its activities in State B (assume constituting PE of A Co in State B), declares dividend to X Co, a resident of State C. This is provided by way of a diagram below.

While State B would tax the profits of the PE of A Co, State B can also seek to tax the dividend paid by A Co to X Co as the profits out of which the dividend is paid is out of profits earned in State B. In such a situation, the DTAA between State C and State B may not be able to restrict State B from taxing the dividends if the Article dealing with Other Income does not provide exclusive right of taxation to the country of residence. In such a scenario, Article 10(5) of the DTAA between State A and State B will prevent State B from taxing the dividends on the following grounds:

a. A Co, the company paying the dividends, is not a resident of State B;

b. C Co, the recipient of the dividends, is not a resident of State B; and

c. The dividends are not effectively connected to a PE of C Co (the recipient) in State B.

9. CONCLUSION

With the return to the classical system of taxing dividends, dividends may now be a tax-efficient way of distributing the profits of a company, especially if the shareholder is a resident of a country with a favourable DTAA with India. In certain cases, distribution of dividend may be a better option as compared to undertaking buyback on account of the buyback tax in India.

However, it is important to evaluate the anti-avoidance rules such as the beneficial ownership rule as well as the MLI provisions before applying the treaty benefit. As a CA certifying the remittance in Form 15CB, it is extremely important that one evaluates the documentation to substantiate the above anti-avoidance provisions and, in the absence of the same, not provide benefit of the DTAA to such dividend income. In the next part of this article, relating to international tax aspects of taxation of dividends, we would cover certain specific issues such as whether DDT is restricted by DTAA, MLI aspects and underlying tax credit among other issues in respect of dividends.