A. ARTICLE 3 – Hybrid mismatch arrangement

Instances of entities treated differently by countries for taxation are commonplace. A partnership is a taxable person under the Indian Income-tax Act, 1961, while in the United Kingdom a partnership has a pass-through status for tax purposes, with its partners being taxed instead. The problems caused by such asymmetric treatment of entities as opaque or transparent for taxation by the Contracting States is well-documented. There have been attempts to regulate the treatment of such entities, notably the 1999 OECD Report on Partnerships and changes made to the Commentary on Article 1 of the OECD Model in 2003. One common problem where Contracting States to a tax treaty treat an entity differently for tax purposes is double non-taxation. Let us take the following example, which illustrates double non-taxation of an entity’s income:

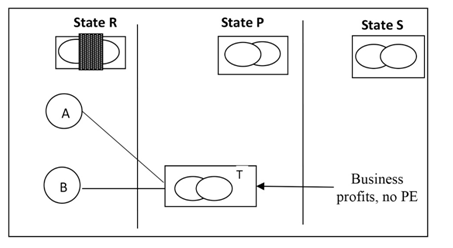

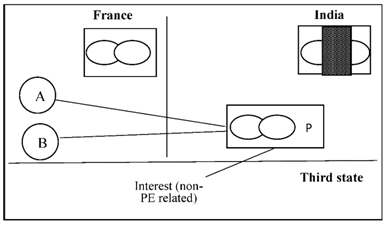

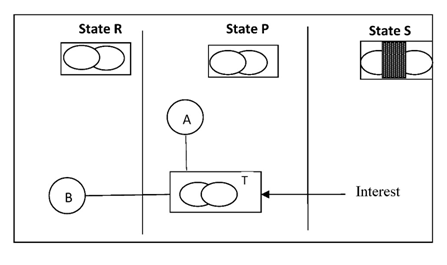

Example 1: T is an entity established in State P. A and B are members of T residing in State R. State P and State S treat the entity as transparent, but State R treats it as a taxable entity. T derives business profits from State S that are not attributable to a permanent establishment in State S.

Figure 1

State S treats entity T as fiscally transparent and recognises the business profits as belonging to members A and B, who are residents of State R. Applying the State R-S Treaty, State S is barred from taxing the business profits without a PE. On the other hand, State R does not flow through the partnership’s income to its partners. Accordingly, State R treats entity T as a non-resident and does not tax the income or tax its partners A and B. The double non-taxation arises because both State R and State S treat the entity differently for taxation. Another problem is that an entity established in State P could have partners / members belonging to third countries (as in Figure 1 above), encouraging treaty shopping.

1.1 Income derived by or through fiscally transparent entities [MLI Article 3(1)]

The Action 2 Report of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project on Hybrid mismatch arrangements (‘Action 2 Report’) deals with applying tax treaties to hybrid entities, i.e., entities that are not treated as taxpayers by either or both States that have entered into a tax treaty. Common examples of such hybrid entities are partnerships and trusts. The OECD Commentary on Article 1 of the Model (before its 2017 Update) contained several paragraphs describing the treatment given to income derived from fiscally transparent partnerships based on the 1999 Partnership Report.

As per the recommendation in the Action 2 Report, Article 3(1) of the Multilateral Instrument (‘MLI’) inserts a new provision in the Covered Tax Agreements (‘CTA’) which is to ensure that treaties grant benefits only in appropriate cases to the income derived through these entities and further to ensure that these benefits are not granted where neither State treats, under its domestic law, the income of such entities as the income of one of its residents. A similar text has also been inserted as Article 1(2) in the OECD Model (2017 Update).

Article 3(1) reads as under:

For the purposes of a Covered Tax Agreement, income derived by or through an entity or arrangement that is treated as wholly or partly fiscally transparent under the tax law of either Contracting Jurisdiction shall be considered to be income of a resident of a Contracting Jurisdiction but only to the extent that the income is treated, for purposes of taxation by that Contracting Jurisdiction, as the income of a resident of that Contracting Jurisdiction.

The impact of Article 3(1) on a double tax avoidance agreement can be illustrated in the facts of Example 1 above. Unless State R ‘flows through’ the income of the entity T to its partners for taxation and tax the income sourced in State S as income of its residents, State S is not required to exempt or limit its taxation as a Source State while applying the R-S Treaty. State S will also not apply the P-S Treaty since the income belongs to the partners of entity T who are not residents of State P. The Source State is expected to give treaty benefits only to the extent the entity’s income is treated for taxation by the Residence State as the income of its residents. The following example illustrates this:

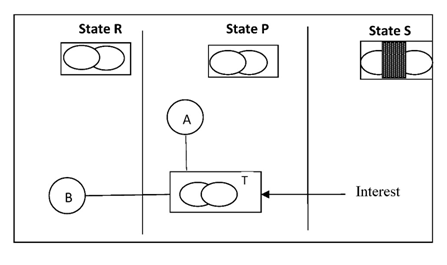

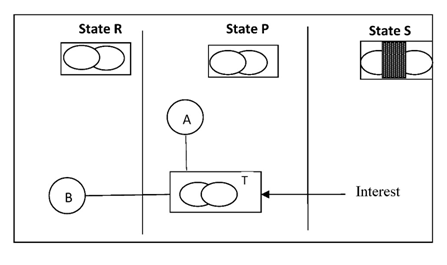

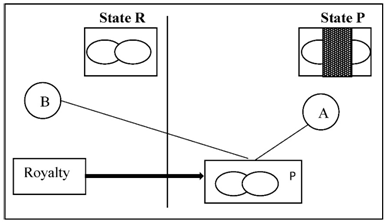

Example 2: A and B are entity T’s members residing in State P and R, respectively. States R and P treat the entity as transparent, but State S treats it as a taxable entity. A derives interest arising in State S. There is no treaty between State R and State S.

Figure 2

In this example, State S will limit its taxation of interest arising in that State under the P-S Treaty to the extent of the share of A in the profits of P. The income derived from the entity by the other member B will not be considered by State S to belong to a resident of State P and it will not extend the P-S treaty to that portion of income. Since there is no R-S treaty, State S will tax the income derived by member B from the entity as per its domestic law.

The OECD Commentary

As per paragraph 7 of the Commentary on Article 1 in the OECD Model (2017 Update), any income earned by or through an entity or arrangement which is treated as fiscally transparent by either Contracting States will be covered within the scope of Article 1(2) [which is identical to Article 3(1) of the MLI] regardless of the view taken by each Contracting State as to who derives that income for domestic tax purposes, and regardless of whether or not that entity or arrangement has a legal personality or constitutes a person as defined in Article 3(1) of the Convention. It also does not matter where the entity or arrangement is established: the paragraph applies to an entity established in a third State to the extent that, under the domestic tax law of one of the Contracting States, the entity is treated as wholly or partly fiscally transparent, and income of that entity is attributed to a resident of that State. State S is required to limit application of its DTAA only to the extent the other State (State R or State P, as the case may be) would regard the income as belonging to its resident. Thus, when we look at the facts in Example 2 above, the outcome will not change even if the entity T is established in State R (or a third state which has a treaty with State S) so long as that State flows through the income of the entity to a member resident in that State.

In other words, State S applies the P-S Treaty because A is a resident of State P and is taxed on his share of income from entity T and not because the entity is established in that State. Similarly, if a treaty exists between State R and State S, State S shall apply that treaty only to the extent of income which State R regards as income of its resident (B in this case).

However, India has expressed its disagreement with the interpretation contained in paragraph 7 of the Commentary. It considers that Article 1(2) covers within its scope only such income derived by or through entities that are resident of one or both Contracting States. Article 4(1)(b) of the India-USA DTAA (which is not a CTA) is on the lines of Article 3(1) of the MLI. On the other hand, Article 1 of the India-China Treaty (which was amended vide a Protocol in 2018 and not through the MLI) requires the entity or arrangement to be established in either State and to be treated as wholly fiscally transparent under the tax laws of either State for the rule on fiscally transparent entities to apply.

Impact on India’s treaties

India has reserved the application of the entirety of Article 3 of the MLI relating to transparent entities from applying to its CTAs, which means that this Article will not apply to India’s treaties. A probable reason could be that India finds it preferable to bilaterally agree on any enhancement of scope of the provisions relating to transparent partnerships to other fiscally transparent entities only after an examination of its impact bilaterally rather than accept Article 3(1) in the MLI, which would have applied across the board to all its CTAs.

1.2 Income derived from fiscally transparent entities – Elimination of double taxation [MLI Article 3(2)]

Action 6 Report of the BEPS Project on Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in Inappropriate Circumstances (‘Action 6 Report’) recommends changes to the provisions relating to the elimination of double taxation. Article 3(2) of the MLI is intended to modify the application of the provisions related to methods for eliminating double taxation, such as those found in Articles 23A and 23B of the OECD and UN Model Tax Conventions. Often, such situations arise in respect of income derived from fiscally transparent entities. For this reason, this provision has been inserted in Article 3 of the MLI which deals with transparent entities. Article 3(2) of the MLI reads as follows:

Provisions of a Covered Tax Agreement that require a Contracting Jurisdiction to exempt from income tax or provide a deduction or credit equal to the income tax paid with respect to income derived by a resident of that Contracting Jurisdiction which may be taxed in the other Contracting Jurisdiction according to the provisions of the Covered Tax Agreement shall not apply to the extent that such provisions allow taxation by that other Contracting Jurisdiction solely because the income is also income derived by a resident of that other Contracting Jurisdiction. [emphasis supplied]

The article on eliminating double taxation in a tax treaty obliges the Contracting States to provide relief of double taxation either under exemption or credit method where the other State taxes the income of a resident of the first State in accordance with that treaty. However, there may be cases where each Contracting State taxes the same income as income of one of its residents and where relief of double taxation will necessarily be with respect to tax paid by a different person. For example, an entity is taxed as a resident by one State while it is treated as fiscally transparent, and its members are taxed instead, in the other State, with some members taxed as residents of that other State. Thus, any relief of double taxation will need to take into account the tax that is paid by different taxpayers in the two States.

Action 6 Report notes that, as a matter of principle, Articles 23A and 23B of the OECD Model require a Contracting State to relieve double taxation of its residents only when the other State taxed the relevant income as the Source State or as a State where there is a permanent establishment to which that income is attributable. The Residence State need not relieve any double taxation arising out of taxation imposed by the other State in accordance with the provisions of the relevant Convention solely because the income is also income derived by a resident of that State. In other words, the obligation to extend relief lies only with that State which taxes an income of a person solely because of his residence in that State. Other State which may tax such income because of both source and residence need not extend relief. This will obviate cases of double taxation relief resulting in double non taxation.

The OECD Commentary gives some examples to illustrate the scope of this provision. Some of these examples are discussed here in the context of the India-France DTAA for the reader to relate to them more easily.

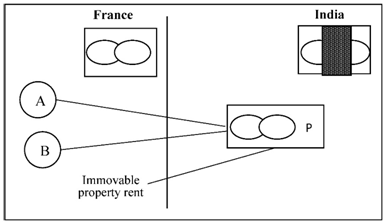

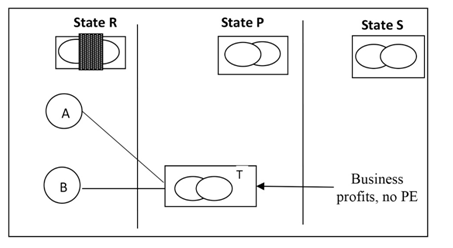

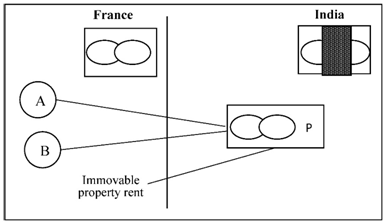

Example 3: The partnership P is an Indian resident under Article 4 of the India-France DTAA. In France, the partnership is fiscally transparent and France taxes both partners A and B as they are its residents.

Figure 3

The only reason France may tax P’s profits in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty is that the partners of P are its residents and not because the income arises in France. In this example, France is taxing income of A and B solely on residence whereas India is taxing income of P on both residence and source. Thus, India is not obliged to give credit to P for the French taxes paid by the partners on their share of profit of P. On the other hand, France will be required to provide relief under Articles 23 with respect to the entire income of P as India may tax that income in accordance with the provisions of Article 7. This is even though India taxes the income of P, which is its resident. The Indian taxes paid by P will have to be considered for exemption under Article 23 against French taxes payable by the partners in France.

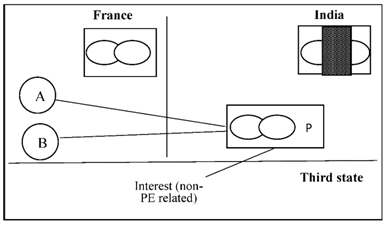

Example 4: Income from immovable property situated in other State

Figure 4

The facts are the same as in Example 3 except that P earns rent from immovable property in France. In this example, France is taxing income of A and B on residence and source whereas India is taxing income of P solely on residence. Thus, India is obliged to give credit for French taxes paid, which is in accordance with Article 6 of the India-France Treaty even though France taxes the income derived by the partners who are French residents. On the other hand, France is not obliged to give credit for Indian taxes, which are paid only because P is resident in India and not because income is sourced in India. However, both India and France have to give credit to tax paid in third State as per their respective DTAAs with the third State. If there is no DTAA with the third State, credit may be given as per the respective domestic law [viz., section 91 of IT Act]. Both India and France giving FTC is not an aberration as both would have included income from third State in taxing their residents.

Example 5: Interest from a third state

Figure 5

Here, the facts are the same as in Example 3 except that P earns interest arising in a third State. France taxes the interest income in the hands of the partners only because they are French residents. Consequently, India is not obliged to grant credit for French taxes paid by the partners in France. In this case, India is not obliged to give credit for French taxes paid in accordance with the India-France Treaty only because the interest is derived by the partners who are French residents. Also, France is not obliged to give credit for Indian taxes paid in accordance with the Treaty only because P is resident in India and not because income is sourced in India.

The above discussion is also relevant for countries that have opted for the credit method in Option C through Article 5(6) of the MLI since that Option contains text similar to that contained in Article 3(2).

1.3 Right to tax residents preserved for fiscally transparent entities [MLI Article 3(3)]

It is commonly understood that tax treaties are designed to avoid juridical double taxation. However, treaties have been interpreted in a manner to restrict the Resident State from taxing its residents. Article 11 of the MLI contains the so-called ‘savings clause’ whereby a Contracting State shall not be prevented by any treaty provision from taxing its residents. Article 3(3) of the MLI provides for a similar provision for fiscally transparent entities. The saving clause, as introduced by Article 11, is discussed in greater detail elsewhere in this article.

Impact on India’s treaties

Since India has reserved the entirety of Article 3 of the MLI, paragraphs 2 and 3 also do not apply to modify any of India’s CTAs.

B. ARTICLE 5 – Methods of elimination of double taxation

Double non-taxation arises when the Residence State eliminates double taxation through an exemption method with respect to items of income that are not taxed in the Source State. Article 5 of the MLI provides three options that a Contracting Jurisdiction could choose from to prevent double non-taxation, which is one of the main objectives of the BEPS project. These are described below:

2.1 Option A

Article 23A of the OECD Model Convention provides for the exemption method for relieving double taxation. There have been instances of income going untaxed in both States due to the Source State exempting that income by applying the provisions of a tax treaty, while the Resident State also exempts the same. Paragraph 4 of Article 23A of the OECD Model addresses this problem by permitting the Residence State to switch from the exemption method to the credit method where the other State has not taxed that income in accordance with the provisions of the treaty between them.

As explained in the OECD Model (2017) Commentary on Article 23A (paragraph 56.1), the purpose of Article 23A(4) is to avoid double non-taxation as a result of disagreements between the Residence State and the Source State on the facts of a case or the interpretation of the provisions of the Convention. An instance of such double non-taxation could be where the Source State interprets the facts of a case or the provisions of a treaty in such a way that a treaty provision eliminates its right to tax an item of income. At the same time, the Residence State considers that the item may be taxed in the Source State ‘in accordance with the Convention’ which obliges it to exempt such income from tax.

The BEPS Action 2 Report on Hybrid Arrangements recommends that States which apply the exemption method should, at the minimum, include the ‘defensive rule’ contained in Article 23A(4) in the tax treaties where such provisions are absent. As per Option A, the Residence State will not exempt such income but switch to the credit method to relieve double taxation of its residents [MLI-A 5(3)]. For example, Austria and the Netherlands, both of whom adopt the exemption method to relieve double taxation of their residents, have chosen Option A and have notified the relevant article eliminating double taxation present in the respective CTAs with India. The deduction from tax in the Residence State shall be an ordinary credit not exceeding the tax attributable to the income or capital which may be taxed in the other State.

2.2 Option B

One of the instances of base erosion is commonly found under a hybrid mismatch arrangement where payments are deductible under the rules of the payer jurisdiction but not included in the ordinary income of the payee or a related investor in the other jurisdiction. The Action 2 Report recommends introducing domestic rules targeting deduction / no inclusion outcomes (‘D/NI outcomes’). Under this recommended rule, a dividend exemption provided for relief against economic double taxation should not be granted under domestic law to the extent the dividend payment is deductible by the payer.

In a cross-border scenario, several treaties provide an exemption for dividends received from foreign companies with substantial shareholding. To counter D/NI outcome from such treatment, insertion of a provision akin to Article 23A(4) (described above under Option A) provides only a partial solution. Option B found in Article 5(4) of the MLI permits the Residence State of the person receiving the dividend to apply the credit method instead of the exemption method generally followed by it for dividends deductible in the payer State. None of India’s treaty partners has chosen this Option.

2.3 Option C

Action 2 Report also recommends States to not include the exemption method but opt for the credit method in their treaties as a more general solution to the problems of non-taxation resulting from potential abuses of the exemption method. Option C implements this approach wherein the credit method would apply in place of the exemption method provided for in tax treaties. The deduction from tax in the Residence State shall be an ordinary credit not exceeding the tax attributable to the income or capital which may be taxed in the other State.

The text of Option C contains the words in parenthesis, ‘except to the extent that these provisions allow taxation by that other Contracting Jurisdiction solely because the income is also income derived by a resident of that other Contracting Jurisdiction’. These words are similar to the MLI provision in Article 3(2) relating to fiscally transparent entities. The reader can refer to the discussion under Article 3(2) above, which describes the import of these words, which have also been added in Article 23A-Exemption Method and Article 23B-Credit Method in the OECD Model (2017). As per paragraph 11.1 of the Commentary on Articles 23A and 23B, this rule is merely clarificatory. Even in the absence of the phrase, the rule applies based on the current wording of Articles 23A and 23B.

2.4 Asymmetric application

Article 5 of the MLI permits an asymmetric application with the options chosen by each State applying with respect to its residents. For example, India has chosen Option C which applies to the provisions for eliminating double taxation to be followed by India in its treaties for its residents. The provisions in a treaty to eliminate double taxation by the other State are not affected by India’s choice of Option. Similarly, the other State’s choice also does not affect the provision relating to India. For example, the Netherlands has opted for Option A, while the Elimination article in the treaty for India will not get modified as India has not notified the CTA provision.

2.5 Impact of India’s treaties

India’s treaties generally follow the ordinary credit method to eliminate double taxation of its residents barring a few countries where it adopts the exemption method. India has opted for Option C, which will apply in place of the exemption method in the CTAs, where it follows the exemption method. Accordingly, India has notified its CTAs with Bulgaria, Egypt, Greece and the Slovak Republic. Greece and Bulgaria have reserved the application of Article 5 of the MLI, due to which their CTAs with India are not modified. Both India and the Slovak Republic have chosen Option C and both countries have moved from the exemption method in their CTA to the credit method. As for its CTA with Egypt, India’s Option C applies for its residents while Egypt has not selected any option and the exemption method in the CTA continues to apply to its residents. By opting for Option C with the Slovak Republic and Egypt, India has impliedly applied MLI 3(2) which it has otherwise reserved in entirety.

Of the other countries which apply the exemption method to relieve double taxation of their residents in India’s treaties, Austria and the Netherlands have opted for Option A and notified the CTA provisions. Estonia and Luxembourg, too, follow the exemption method for their residents in their CTA with India. Yet, though they have opted for Option A, they have not notified the relevant provisions and the CTAs shall remain unmodified. Presumably, since the India-Luxembourg DTAA already contains provisions of the nature contained in Option A, and under the India-Estonia treaty, Estonia exempts only that income from taxation taxed in India, these jurisdictions have chosen not to avail of the defensive rule provided in the MLI.

C. ARTICLE 11 – Saving of a State’s right to tax its own residents

3.1 Rationale

A double tax treaty is entered into with the object of relieving juridical double taxation. The double taxation is relieved, either by allocating the taxing rights to one of the contracting States to that treaty, or eliminated by the relief provisions through an exemption or credit method. However, treaties have sometimes been interpreted to restrict the Resident State from taxing its residents in some instances.

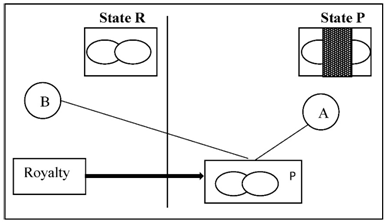

One example would be to interpret the phrase ‘may be taxed in the source State’ as ‘shall only be taxed in the source State’, thereby denuding the right of the Residence State to tax its resident. Another example is a partnership that is resident of State P with one partner resident of State R. State P taxes the partnership while State R treats the partnership as transparent and taxes the partners.

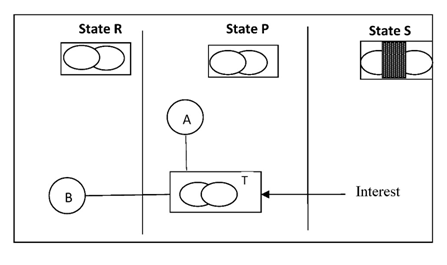

Figure 6

The partnership P is resident of State P and is entitled to the P-R Treaty, similar to the OECD Model. If the partnership earns royalty income arising in State R, State R is not entitled to tax the same as per Article 12(1) of the OECD Model which allocates the taxing right only to the residence state, State P. Thus, the partner resident in State R could argue, based on the language of Article 12(1), that State R does not have the right to tax him on his share of the royalty income earned by the partnership since the P-R treaty restricts the taxing right of State R.

However, many countries disagree with this interpretation. Article 12 applies to royalties arising in one State and paid to a resident of the other State. When taxing partner B, State R is taxing its resident on income arising in its territory. To clarify that State R is not prevented from taxing its residents, paragraph 6.1 was inserted to the Commentary on Article 1 of the OECD Model, which reads as under:

‘Where a partnership is treated as a resident of a Contracting State, the provisions of the Convention that restrict the other Contracting State’s right to tax the partnership on its income do not apply to restrict that other State’s right to tax the partners who are its own residents on their share of the income of the partnership. Some states may wish to include in their conventions a provision that expressly confirms a Contracting State’s right to tax resident partners on their share of the income of a partnership that is treated as a resident of the other State.’

The BEPS Report on Action 6 – Preventing Treaty Abuse concluded that the above principle reflected in paragraph 6.1 of the Commentary on Article 1 should be more generally applied to prevent interpretations intended to circumvent the application of a Contracting State’s domestic anti-abuse rules. The report recommends that the principle that treaties do not restrict a State’s right to tax its residents (subject to certain exceptions) should be expressly recognised by introducing a new treaty provision. The new provision is based on the so-called ‘saving clause’ usually found in US tax treaties. The object of such a clause is to ‘save’ the right of a Contracting State to tax its residents. In contrast to the savings clause in the US treaties that apply to residents and citizens, the savings clause inserted into the covered tax agreements by Article 11 of the MLI applies only to residents. The savings clause inserted by Article 11 of the MLI plays merely a clarifying role, unlike the substantial role of the US savings clause due to its more extensive scope.

Article 11 of the MLI is aimed at the Residence State and its tax treatment of its residents. This provision does not impact the source taxation of non-residents. There are several exceptions to this principle listed in Article 11 of the MLI where the rights of the Resident State to tax its residents are intended to be restricted:

a) A correlative or a corresponding adjustment [a provision similar to Article 7(3) or 9(2) of the OECD Model] to be granted to a resident of a Contracting State following an initial adjustment made by the other Contracting State in accordance with the relevant treaty on the profits of a permanent establishment of that enterprise or an associated enterprise;

b) Article 19, which may affect how a Contracting State taxes an individual who is resident of that State if that individual derives income in respect of services rendered to the other Contracting State or a political subdivision or local authority thereof;

c) Article 18 which may provide that pensions or other payments made under the social security legislation of the other Contracting State shall be taxable only in that other State;

d) Article 18 which may provide that pensions and similar payments, annuities, alimony payments, or other maintenance payments arising in the other Contracting State shall be taxable only in that other State;

e) Article 20, which may affect how a Contracting State taxes an individual who is a resident of that State if that individual is also a student who meets the conditions of that Article;

f) Article 23, which requires a Contracting State to provide relief of double taxation to its residents with respect to the income that the other State may tax in accordance with the Convention (including profits that are attributable to a permanent establishment situated in the other Contracting State in accordance with paragraph 2 of Article 7);

g) Article 24, which protects residents of a Contracting State against certain discriminatory taxation practices by that State (such as rules that discriminate between two persons based on their nationality);

h) Article 25, which allows residents of a Contracting State to request that the competent authority of that State consider cases of taxation not in accordance with the Convention;

i) Article 28, which may affect how a Contracting State taxes an individual who is resident of that State when that individual is a member of the diplomatic mission or consular post of the other Contracting State;

j) Any provision in a treaty which otherwise expressly limits a Contracting State’s right to tax its residents or provides expressly that the Contracting State in which an item of income arises has the exclusive right to tax that item of income.

The last item [at serial (j) above] is a residuary provision that refers to the distributive rules granting the Source State the sole right to tax an item of income. For example, Article 7(1) of the India-Bangladesh DTAA provides that the State where a PE is situated has the sole right to tax the profits attributable to that PE and is not impacted by the savings clause. Treaty provisions expressly limiting the tax rate imposable by a Contracting State on its residents are also covered by the exception to the savings clause. An example of such a provision is contained in Article 12(1) of the Israel-Singapore Treaty which states: ‘Royalties arising in a Contracting State and paid to a resident of the other Contracting State may be taxed in that other State. However, the tax so charged in the other Contracting State shall not exceed 20 per cent of the amount of such royalties.’

3.2 Dual-resident situations

The saving clause in Article 11 of the MLI applies to taxation by a Contracting State of its residents. The meaning of residents flows from Article 4 (dealing with Residence) of the tax treaties and not from the domestic tax law. Thus, where a person is resident in both Contracting States within the meaning of Article 4 of the treaty, the tie-breaker rule in Article 4(2) or (3) will determine the State where that person is resident, and the saving clause shall apply accordingly. The State that loses in the tie-breaker does not benefit from the savings clause to retain taxing right over that person even though he is its resident as per its domestic tax law.

3.3 Application of domestic anti-abuse rules

A savings clause also achieves another objective of preserving anti-abuse provisions by the Resident State like the ‘controlled foreign companies’ (‘CFC’) rules. In a CFC regime, the Resident State taxes its residents on income attributable to their participation in certain foreign entities. It has sometimes been argued, based on a possible interpretation of provisions of the Convention such as paragraph 1 of Article 7 and paragraph 5 of Article 10, that this common feature of CFC legislation conflicted with these provisions. The OECD Model Commentary (2017 Update) on Article 1 in paragraph 81 states that Article 1(3) of the Model (containing the saving clause) confirms that any legislation like the CFC rule that results in a State taxing its residents does not conflict with tax conventions.

3.4 India’s position and impact on India’s treaties

India has not made any reservation for the application of Article 11. Forty-one countries have reserved their application leaving 16 CTAs to be modified by inserting the savings clause. Article 11 of the MLI will have only a limited effect on India’s treaties as India does not have domestic CFC rules and treats partnerships as fiscally opaque. However, it is possible that the interpretation of the courts of the distributive rule ‘may be taxed’ in the Source State as ‘shall be taxed only’ in the Source State, thus preventing the taxation by India of such income of its residents could be impacted.

In CIT vs. R.M. Muthaiah [1993] 202 ITR 508 (Kar), the High Court, interpreting the words ‘may be taxed’ in the context of the India-Malaysia Treaty, held that ‘when a power is specifically recognised as vesting in one, exercise of such a power by other, is to be read, as not available; such a recognition of power with the Malaysian Government would take away the said power from the Indian Government; the Agreement thus operates as a bar on the power of the Indian Government in the instant case.’ The High Court concluded that India could not tax its residents on such income. Article 11 of the MLI could undo the decision to enable India to tax its residents, notwithstanding the said ruling. On the other hand, an alternative interpretation could be that ‘may be taxed’ or ‘shall only be taxed’ are distributive rules in treaties that expressly allocate taxing rights to one or both the Contracting States and are covered by the exception listed in Article 11(1)(j) reproduced above. The saving clause is not targeted at them.